Report 17-03, January 2017

Legislative Auditor's Conclusion: Homeless youth programs need specific performance measures. Ability to evaluate outcomes hindered by state limits on collecting personal data.

- Executive summary

- Report details

- Recommendations and agency response

- More about the study

- Contact information

In 2015, the Legislature passed the Homeless Youth Prevention and Protection Act (2SSB 5404)

The Act:

- Directed the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Committee (JLARC) to review state-funded programs and services provided to unaccompanied homeless youth under age 18;

- Created a new office in the Department of Commerce (Commerce) to manage programs for unaccompanied homeless youth and young adults;

- Moved three youth programs from the Department of Social and Health Services (DSHS) to Commerce; and

- Set goals for addressing youth homelessness.

The Legislative Auditor concludes that state limits on collecting personal data will hinder the ability to evaluate the program outcomes for unaccompanied homeless youth. Further, these programs need specific performance measures.

- Washington provides funding for a street outreach program (Street Youth Services) and two short-term residential programs (Crisis Residential Centers and HOPE Centers). Commerce became responsible for managing these programs in July 2015. It signed new grant agreements with private organizations (providers) across the state to continue operating the programs through June 30, 2017.

- Commerce collects data from providers through the information management system it uses for other homelessness programs. Under a current Commerce interpretation of state law, youth cannot consent for their personal data to be entered in the system. This restriction hinders Commerce’s ability to evaluate program outcomes.

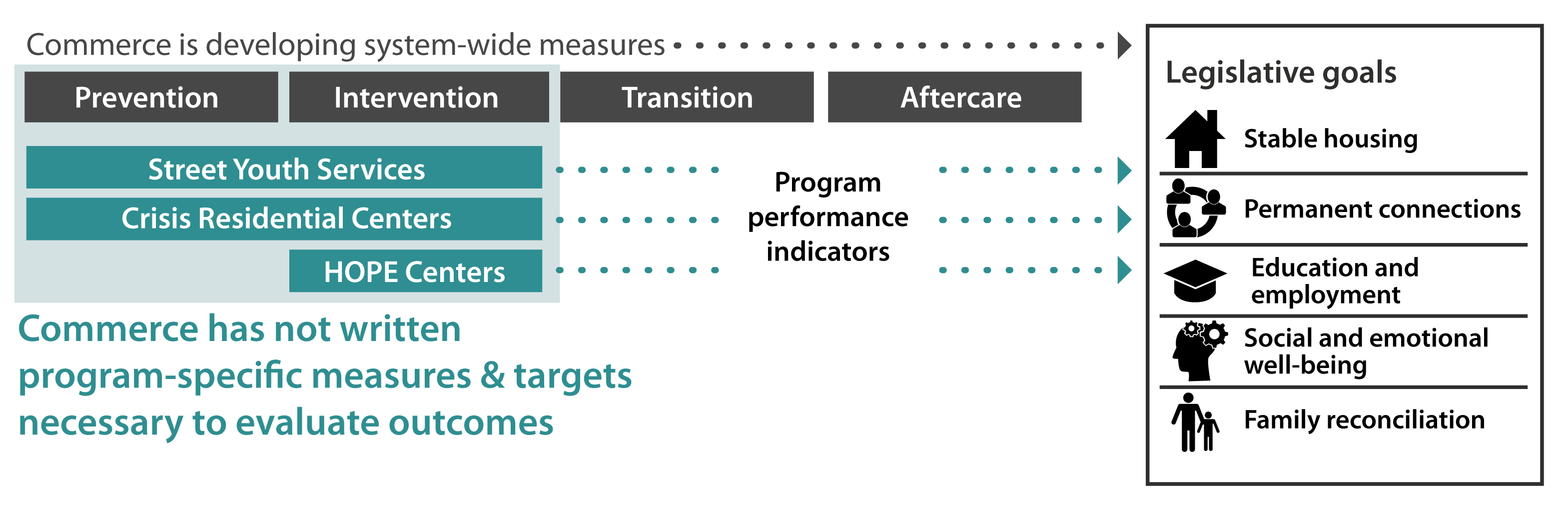

- Commerce is developing system-wide performance measures related to the Legislature’s goals for addressing youth homelessness. Commerce has not developed program-specific measures or included performance targets in its new grant agreements.

- In addition, an all-inclusive number of unaccompanied homeless youth is difficult to estimate. Both Commerce and the Office of the Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI) report counts of unaccompanied homeless youth in Washington. The counts reflect the agencies’ respective federal requirements, which vary in purpose, definitions, and methods. Federal agencies have suggested strategies to improve counts, including better interagency coordination.

The Legislative Auditor recommends three agency actions

- Commerce should brief relevant legislative committees about how current consent law is interpreted, its effect on collecting data from homeless youth, and the potential impacts and trade-offs of collecting this data to evaluate program outcomes.

- Commerce should develop program-specific performance measures. Commerce should incorporate performance measurement into grant agreements beginning in fiscal year 2018.

- Commerce and OSPI should issue joint guidance to counties and school districts, and clarify how they can work together to improve estimates of the unaccompanied homeless youth population.

Commerce concurred with the recommendations. OSPI partially concurred with the third recommendation. The recommendations tab has additional information.

- 1. State provides funding for three programs

- 2. Broader network exists

- 3. Data insufficient to answer Legislature's questions

- 4. Limits on data collection will hinder evaluation of outcomes

- 5. Grant agreements need specific performance measures

- 6. Population estimates vary widely, can be improved

- Appendix 1: Program Locations

- Appendix 2: Program-Specific Measures

Commerce manages agreements with providers for street outreach and residential programs for youth who are homeless or in need of services

Washington provides funding for three programs that serve unaccompanied homeless youth and other eligible youth in need: Street Youth Services, Crisis Residential Centers, and HOPE Centers. The state develops agreements with private organizations (providers) to run the programs. A provider may operate more than one program at one or multiple facilities. Click on the image below to view a slideshow with mapped locations and facility photos in Appendix 1.

Street Youth Services program connects youth with basic supplies and needed services

Five providers in Washington offer state-funded Street Youth Services. While specific operations vary, they use the same general approach. Providers make contact with youth on the street or in day drop-in centers. Providers offer food and basic supplies, and they encourage youth to work with case managers. It is common for youth to interact with outreach workers many times before entering case management. Case managers connect youth to other services, such as emergency housing, physical and mental health care, substance abuse treatment, family reconciliation, and counseling.

Crisis Residential Centers (CRCs) and HOPE Centers provide short-term housing and services.

These residential programs provide temporary housing and services while helping youth reconcile with family or find other housing placements. Exhibit 1.1 compares the programs.

- CRCs provide a brief intervention for runaways and youth in conflict with their families. The intent is to help a youth reconcile with family and return home, or find other safe housing. CRCs can be either secure or semi-secure. Secure facilities are more restrictive and are designed for youth who have the highest risk of running away.

- HOPE Centers provide a longer-term intervention with more intensive case management. Youth who participate may need additional support to return home or find safe housing. Youth are engaged in learning life skills and setting personal goals.

Youth may enter a residential program or a facility more than once, and may move from one program or facility to another. Upon each entry, the provider helps the youth complete a needs assessment. The provider then makes referrals to services such as physical and mental health care, substance abuse treatment, education, and family reconciliation.

| CRC (semi-secure) |

CRC (secure) |

HOPE Centers | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Providers | 6 |

5 |

8 |

| Beds | 45 |

25 |

23 |

| Maximum stay | 15 days |

5 to 15 days |

30 days, plus 30-day extension |

| Placement by: | |||

| Self-referral | |||

| Law enforcement | |||

| DSHS | |||

| Transfer from other program | |||

| Court | |||

State-funded programs serve unaccompanied homeless youth as well as other youth in need

State-funded programs are designed to serve teens who are homeless or in need. The Legislature focused this JLARC study on unaccompanied homeless youth, but other populations may also be eligible for program services. State law and agreements with providers specify who is eligible:

- Unaccompanied homeless youth or street youth: Youth who are under age 18, homeless, and living without a parent or legal guardian.

- Runaways and youth in conflict with their families: Youth who are missing from home or a foster placement without permission. They may be living on the street or be housed (e.g., staying with friends).

- State dependents (i.e., foster youth): DSHS may place foster youth in a residential program under specific circumstances. For example, a foster youth who is close to aging out of foster care could use a HOPE bed before moving into a transitional housing program.

- Court-ordered youth: Courts may order a youth to a CRC or HOPE Center if there is an immediate safety or health concern, family conflict, or truancy. Courts also may order a youth to a secure CRC to serve a detention order.

Providers must contact parents or legal guardians

A provider must notify a youth’s parent or guardian and get their permission for the youth to stay in a CRC or HOPE Center. The youth can stay at the facility while the provider makes documented efforts to contact the adult.

Commerce has managed programs since July 2015

The Office of Homeless Youth Prevention and Protection Programs within the Department of Commerce (Commerce) has been responsible for managing the programs since July 2015. DSHS previously managed the programs and is now responsible only for licensing them.

The Legislature increased funding for these programs in the 2015-17 Biennium:

- During the 2013-15 Biennium, DSHS spent $11.1 million on programs: $1.3 million for Street Youth Services, $8.7 million for Crisis Residential Centers, and $1.2 million for HOPE Centers.

- The Legislature appropriated $14.3 million to Commerce for these programs in the 2015-17 Biennium and directed the Department to increase the number of beds and street outreach programs. Commerce also received $3.1 million for programs that serve homeless young adults and program administration.

The state’s programs are part of a broader network of programs and services involving government and private entities

Street Youth Services, Crisis Residential Centers, and HOPE Centers are part of a broader network of programs and services for unaccompanied homeless youth and other youth in need.

- Federal, state, local, and private entities provide funding for the programs and services.

- Many organizations operate the programs and make referrals to other programs and services. The amount of coordination among these organizations varies.

- Some state-funded providers operate other outreach or shelter programs in addition to Street Youth Services, Crisis Residential Centers, or HOPE Centers. Sometimes programs are co-located.

- There is no common definition of unaccompanied homeless youth across all organizations. Definitions can affect whether a youth is eligible to participate in a program or receive a service. For example, some organizations include individuals up to age 21 or 24. Further, some organizations distinguish between unaccompanied homeless youth, runaways, and youth abandoned by family while others do not.

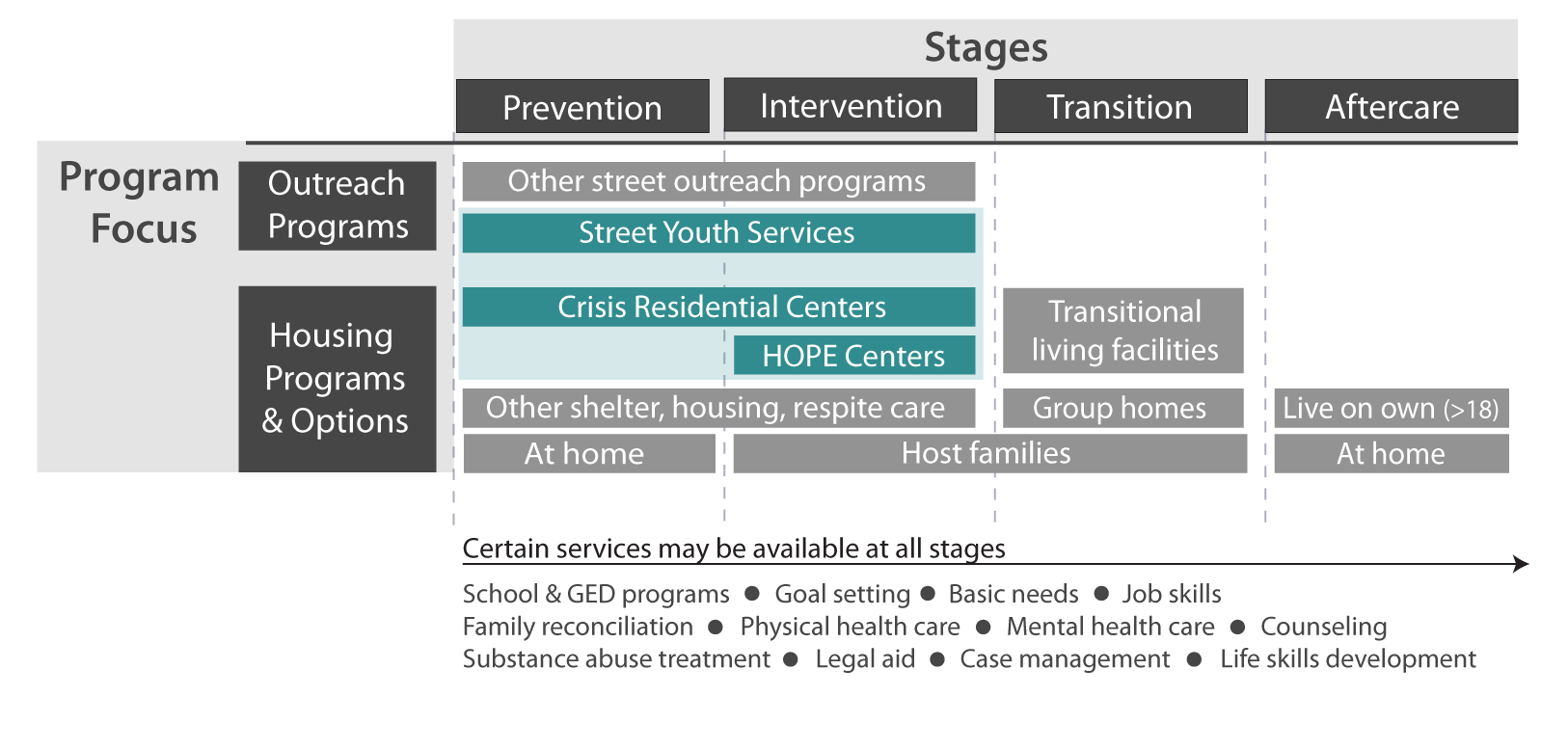

Exhibit 2.1 shows how programs can be grouped into four general stages: Prevention, intervention, transition, and aftercare. The exhibit is not inclusive of all programs and services. State-funded Street Youth Services, Crisis Residential Centers, and HOPE Centers each play a role in the prevention and intervention stages.

DSHS data collection met state requirements, but program effectiveness was not measured

The Legislature directed JLARC staff to identify the statutory reporting requirements for these programs and determine if reliable data existed regarding ages of youth served, length of stay, and effectiveness of program exit and reentry.

Statutory reporting requirements exist for Crisis Residential Centers

There are specific statutory reporting requirements for one of the three programs funded by the State: Crisis Residential Centers (CRCs). As required by statute, the CRCs provided data to DSHS such as the number of youth served, average age, length of stay, reason for entry, and services provided.

Data was collected but not verified or used to evaluate programs

DSHS managed the programs until July 2015. Its provider agreements required monthly data reporting for all three programs.

- CRC and HOPE Center data is reliable enough to provide basic information about the youth served and length of stay (Exhibit 3.1). The program data included personally identifying information about youth such as names and dates of birth, which made it possible for JLARC staff to provide the information below. The data did not allow for an evaluation of program effectiveness or exit and reentry rates.

| CRC (semi-secure) | CRC (secure) | HOPE Centers | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Entries to program | 3,048 | 2,005 | 728 |

| All youth served | 1,601 | 1,296 | 392 |

| Percent of youth served who were state dependents | 61% | 35% | 49% |

| Average age | 15 | 15 | 15 |

| Average length of stay | 7 days | 3 days | 18 days |

- Street Youth Services data is not reliable for answering questions about the youth served. Providers reported aggregate data about the number of contacts made with youth. However, fewer than 40 percent of reports were available and data included services to youth over age 18. Providers collected and reported personally identifying information only when a youth worked with a case manager. While this data collection approach is consistent with the requirements of federal street outreach programs, it does not allow for reports on the number or average age of individuals served.

DSHS collected a broader range of data than is summarized here, but lacked data standards, leading to data entry errors and omissions. Data quality and completeness varied by provider. DSHS did not compile the data received or use the data to assess performance.

Commerce’s data collection approach may improve grant management. State limits on data collection will hinder the ability to evaluate how well programs assist youth

The Legislature gave Commerce the responsibility to manage the programs effective July 2015.

Beginning July 1, 2016, providers of Street Youth Services, Crisis Residential Centers, and HOPE Centers must report data through a homeless management information system (HMIS). Commerce already manages an HMIS for its homeless programs that serve adults, families, and other specific populations. HMIS allows Commerce to compile statewide data from six county-run systems.

However, now that Commerce requires providers to report data in HMIS, they are subject to a state law that requires written consent before including personal data. This law is specific to HMIS. In 2014, the Assistant Attorney General for Commerce advised that only a parent or legal guardian may give consent for a minor. Such consent may be difficult to obtain for unaccompanied homeless youth.

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) funds HMIS databases nationally and issues data standards that all systems must meet. HUD has “strongly encouraged” agencies to relax such restrictions on obtaining consent for collecting data.

Lack of personal data hinders the state’s ability to evaluate how well programs assist youth

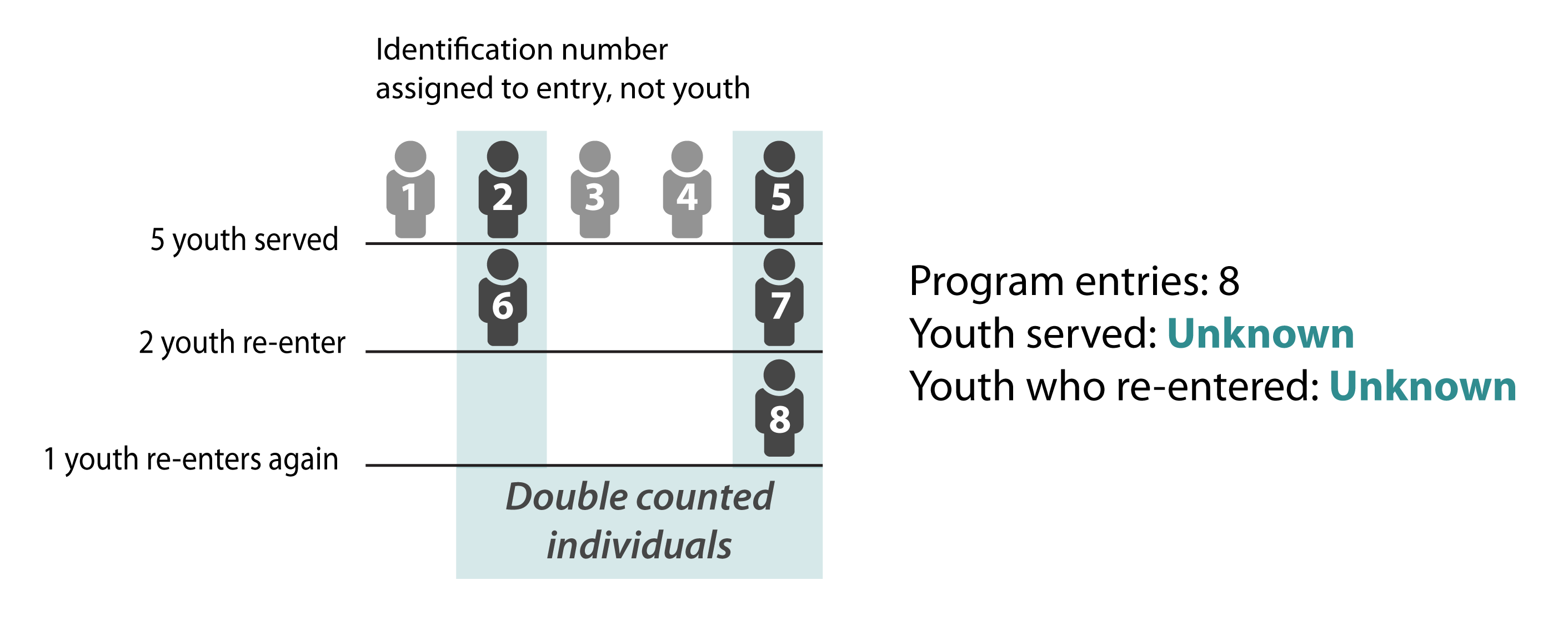

When a provider lacks written consent and cannot submit personal data, HMIS assigns an identification number to the program entry, rather than to the person. This could lead to double counting of a youth who enters a program or facility more than once.

Double counting could limit Commerce’s ability to:

- Accurately calculate program information such as the total number of youth served or the number of youth who enter programs multiple times;

- Evaluate program outcomes such as reentry rates or safe exits; or

- Work with other state agencies to combine HMIS information with other data sets for conducting research about homelessness and risk factors.

Recommendation: Commerce should brief relevant legislative committees about how current consent law is interpreted, its effect on collecting data from homeless youth, and the potential impacts and trade-offs of collecting this data to evaluate program outcomes.

Commerce concurred with this recommendation. The recommendations tab has additional information.

Commerce has begun developing performance measures, but measures are not yet incorporated into grant agreements

Commerce received program management responsibility for Street Youth Services, Crisis Residential Centers, and HOPE Centers in July 2015. Commerce partnered with DSHS to manage the programs for the first year.

Commerce’s new grant agreements do not include performance elements

On July 1, 2016, Commerce signed new grant agreements with all providers that held a DSHS contract to operate Street Youth Services, Crisis Residential Centers, or HOPE Centers. The new grants include clarifying language on parental notification requirements and situations in which state-dependent youth are eligible for residential programs. Commerce made no significant changes to the programs' operations.

While Commerce collects program data through HMIS, the new grant agreements do not include performance targets. State law requires that Commerce use performance-based agreements for Crisis Residential Centers. The law is silent about performance reporting for HOPE Centers and Street Youth Services.

In a separate process, Commerce is considering performance when awarding the additional funds appropriated by the Legislature for fiscal year 2017. In late June, the Department issued a request for proposal that includes narrative election criteria. Commerce will be able to select providers based on factors such as ability to perform the work, services provided, and staffing. Commerce stated an intent to sign these grant agreements by September 1, 2016.

Commerce is developing system-wide outcome measures related to legislative goals

In May 2016, Commerce worked with an advisory committee to draft system-wide outcome measures. The system-wide outcome measures address Commerce’s broad responsibility to coordinate statewide efforts for homeless youth and young adults (i.e., ages 18 to 24). The draft measures are not specific to the operations of the Street Youth Services, Crisis Residential Center, and HOPE Center programs.

The system-wide outcome measures are consistent with the goals set by the Legislature:

- Stable housing;

- Permanent connections;

- Education and employment;

- Social and emotional well-being; and

- Family reconciliation.

These goals align with the outcomes for youth set by the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness (USICH) and the federal Runaway and Homeless Youth (RHY) programs. These entities use or recommend a combination of system-wide outcomes and program-specific measures for evaluating progress toward these goals.

Commerce’s draft measures are consistent with those used in similar programs

Federal programs, national organizations, and some state-funded providers use performance measures for evaluating youth outcomes at both the system and program level:

- Federal RHY programs track the number of youth served, safe and stable exits, and family reconciliation.

- National organizations measure the length of time that a youth experiences homelessness, progress in completing education, access to physical and mental health care, and housing stability.

- Some state providers report using measures and targets to manage operations (e.g., length of stay, utilization, expenditures). Providers also report measuring safe exits and re-entry.

JLARC staff compiled a list of common program-specific measures identified by these groups. Appendix 2 offers potential frameworks for aligning such measures with the Legislature's goals. While not definitive, they include key elements that should be considered in developing program-specific measures.

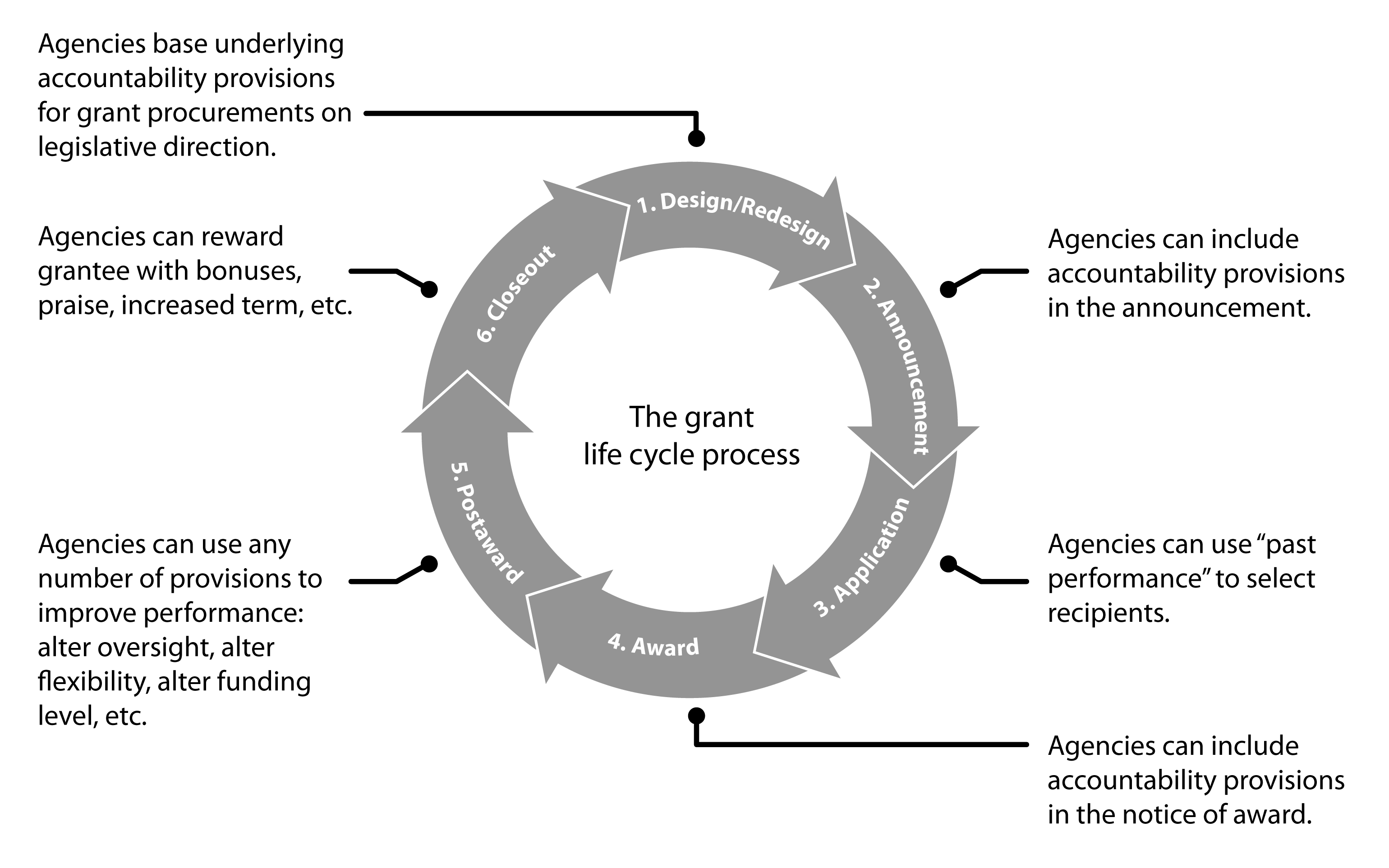

Performance elements can be used throughout grant cycle

Federal grants commonly include performance measures. The U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) notes that these measures can be used at different stages in the grant life cycle (Exhibit 5.1). For example:

- The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) funds many homelessness programs, and requires performance elements in its grant applications.

- The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services operates the RHY programs, and includes performance measures in the grant agreements.

GAO reported in 2006 that the lessons learned from incorporating performance measures into contracts could inform grant design. Other audits and literature suggest that key features of performance-based contracts in social services include:

- Competitive selection (i.e., selecting providers based on their ability to meet performance goals);

- Payment or other incentives linked to clear outcomes, outputs, and quality of service;

- Outcomes, outputs, and quality that are measured and benchmarked;

- Post-contract audits focused on performance; and

- Data to inform managers about progress in meeting organizational goals.

Additional practices include ensuring that data collection is consistent among providers, and working with providers to establish performance measures. These key features and practices can assist Commerce in meeting its programmatic and statutory goals.

Recommendation: Commerce should develop program-specific performance measures. Commerce should incorporate performance measurement into grant agreements beginning in fiscal year 2018.

Commerce concurred with this recommendation. The recommendations tab has additional information.

A comprehensive number of homeless youth is difficult to estimate because commonly reported counts vary in purpose, definitions, and methods

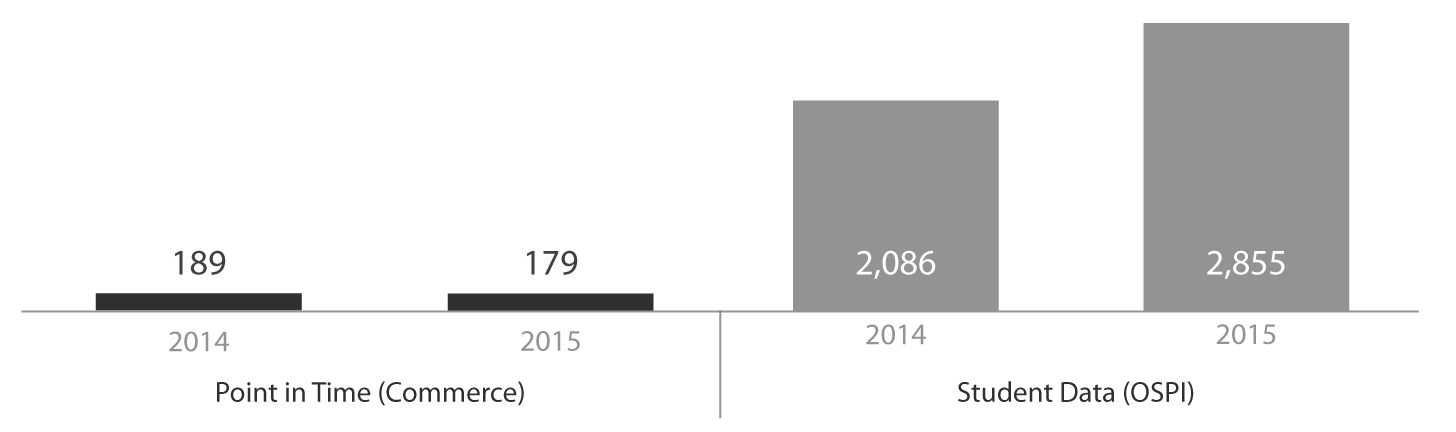

Research shows that unaccompanied homeless youth under 18 are a difficult population to count. The estimates compiled by the Department of Commerce (Commerce) and the Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI) use different definitions, timeframes, and methods for estimating the population. These differences, which reflect federal requirements and are described in more detail below, result in the variation shown in Exhibit 6.1.

Counts are likely low because they exclude some youth by definition and miss others who are difficult to identify

Neither count includes all unaccompanied homeless youth because the purpose of each count varies by federal program, and they use different definitions and counting methods.

- Purpose: Commerce collects data to fulfill a Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) mandate to count a defined segment of the homeless population. OSPI collects data to meet a Department of Education (ED) reporting mandate related to the McKinney-Vento Act. This is a federal law that addresses access to education for homeless youth.

- Definitions: Commerce excludes youth who are staying with friends or family temporarily (e.g., “couch surfing”). OSPI includes these youth, and they make up 85 percent of the youth in the data provided to JLARC staff.

- Method/Timeframe: Commerce receives data that counties collect on a single day (point-in-time) at service locations and through a street count. OSPI collects data from school districts throughout the school year.

Counts also may exclude youth who do not identify as homeless, do not seek shelters or services, live in remote areas, or do not attend school.

The difficulty in counting is not limited to Washington. Homeless counts in general do not use consistent age ranges or definitions of homelessness. A 2010 study by the GAO recommended that a common vocabulary among federal agencies would promote more consistent data, but the varying definitions persist in federal law.

Federal agencies suggest strategies that can improve point-in-time counts

The point-in-time count is widely recognized as an undercount. HUD suggests strategies that its funding recipients could use to improve youth counts. These strategies include:

- Collaborating with school district homelessness liaisons

- Engaging other service organizations (e.g., food banks, health clinics, libraries)

- Recruiting current or former homeless youth to assist with the count

- Using social media to raise awareness and outreach

- Conducting longer or more frequent point-in-time counts

- Using youth-specific surveys

- Identifying homeless youth that meet other definitions of homelessness (e.g., couch-surfing) but report to HUD only those meeting the HUD definition

- Holding magnet events to attract youth to count locations

- Providing services, food, and incentives to youth being counted

The U.S. Department of Education (ED) published a tip sheet in 2015 that encourages education staff to share data with organizations serving homeless youth while respecting limits of federal privacy laws. ED advises that schools and school districts may:

- Discreetly refer homeless youth to community organizations participating in the point-in-time count or hosting magnet events;

- Advise point-in-time count staff and volunteers on where homeless youth congregate; and

- Review personal information about homeless youth provided by the point-in-time count and identify any youth counted more than once, as long as doing so does not violate privacy rules.

Federal strategies to improve counts are not widely used

JLARC staff surveyed Washington’s counties and found that nine counties applied one or more of the HUD strategies in recent counts. Three counties reported working with schools for point-in-time counts. In interviews, count participants indicated some confusion about the type of collaboration allowed.

Recommendation: Commerce and OSPI should issue joint guidance to counties and school districts, and clarify how they can work together to improve estimates of the unaccompanied homeless youth population.

Commerce concurred with this recommendation. OSPI partially concurred and asked JLARC staff to clarify the recommendation. The recommendations tab has additional information.

Washington funds programs across the state that serve unaccompanied homeless youth and other youth in need

The state enters agreements with private organizations (providers) to run Street Youth Services, Crisis Residential Centers, and HOPE Centers. A provider may operate more than one program at one or multiple facilities.

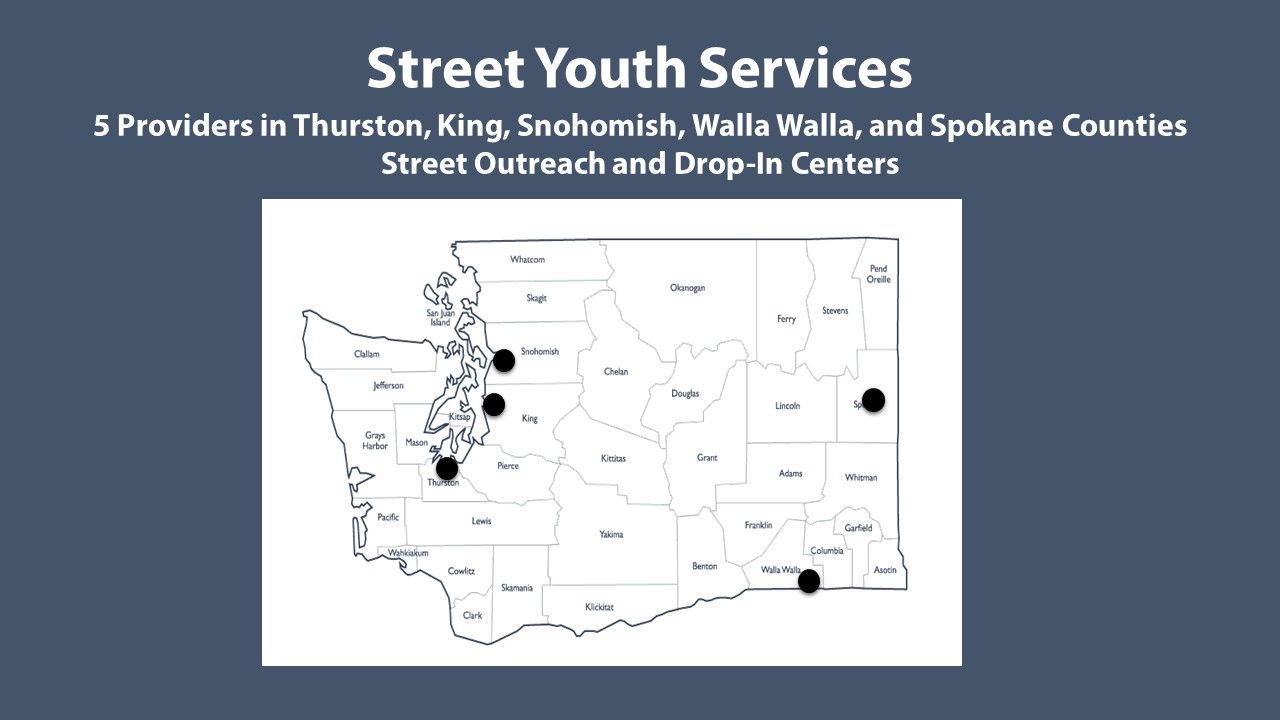

Street Youth Services is designed for unaccompanied homeless youth and youth who are at risk of becoming homeless. The program is offered in Thurston, King, Snohomish, Walla Walla, and Spokane Counties. Providers offer street outreach and drop-in centers.

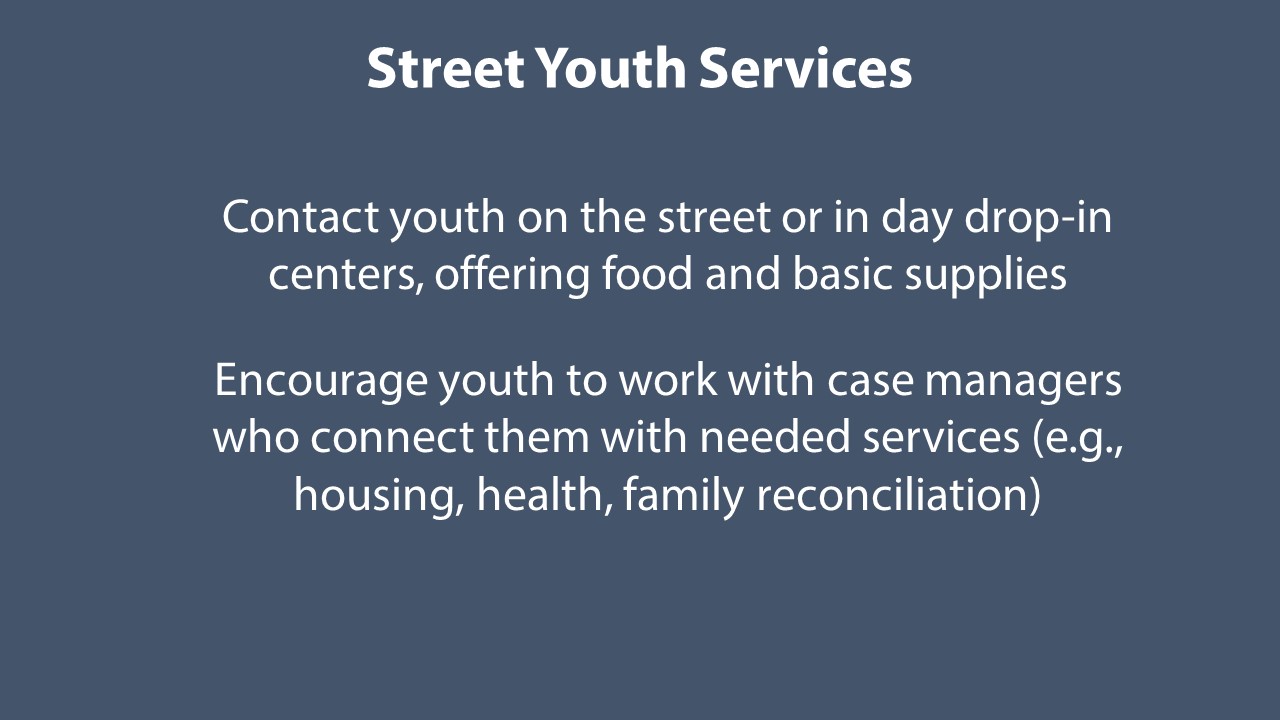

Street Youth Services staff contact youth age 13 to 17. They meet youth on the street, in drop-in centers, or other locations as appropriate (e.g., schools or courts). They offer food and basic supplies such as hygiene kits. They encourage youth to work with case managers who connect them with needed services.

These are photos of Street Youth Services drop in facilities in Snohomish, Spokane, and King counties. The drop-in facilities may offer events and classes to encourage youth engagement.

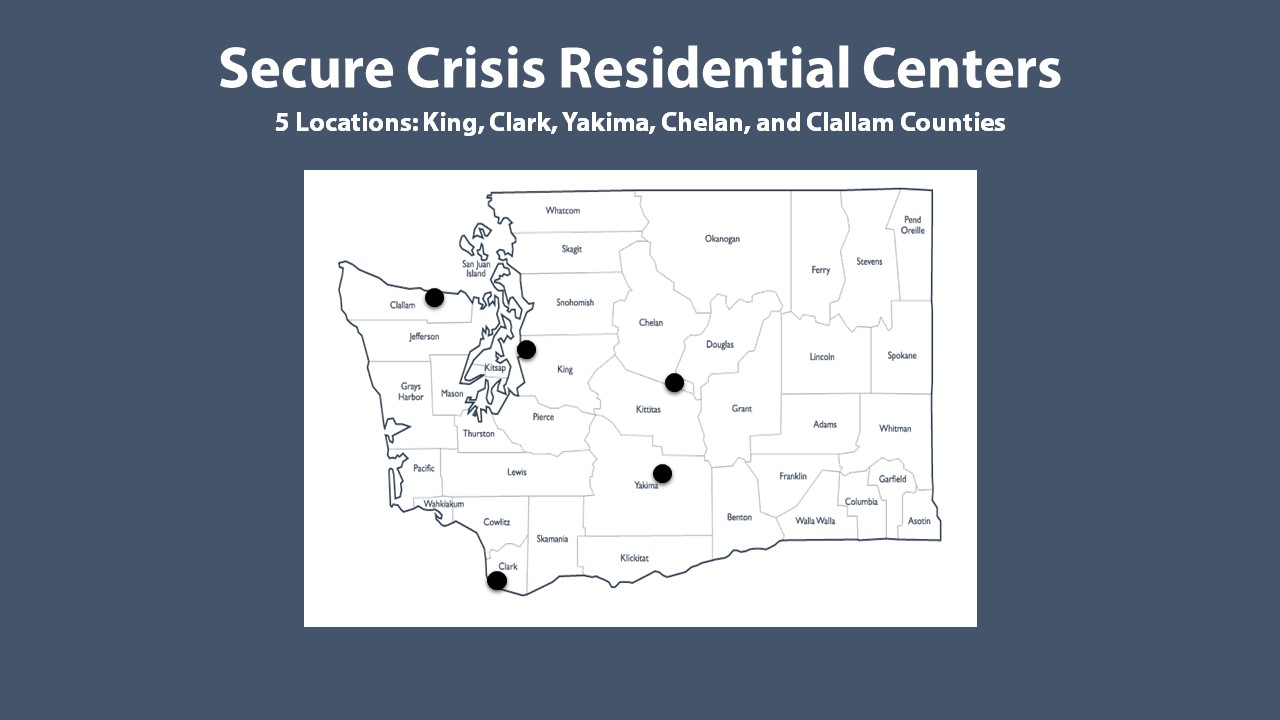

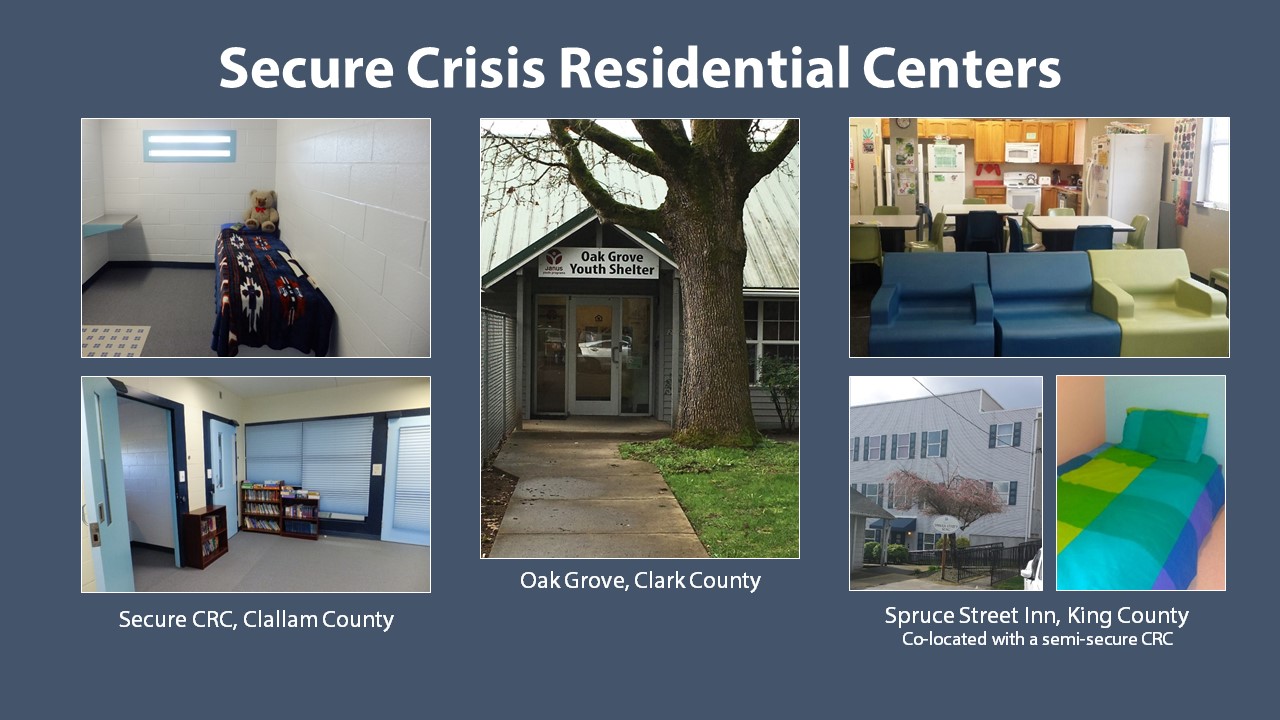

There are 5 Secure Crisis Residential Centers statewide, providing a total of 25 beds for runaways and truant youth who are ordered to the facilities by the court. Secure Crisis Residential Centers are offered in King, Clark, Yakima, Chelan, and Clallam Counties.

Secure Crisis Residential Centers (CRCs) work with youth age 12 to 17. Youth are placed in these facilities by law enforcement, but the placement is not detention. Secure CRCs offer housing and interventions while youth reconcile with family. They are designed with greater security for youth who are most likely to run away. Youth may stay at a secure CRC for 5 to 15 days.

These are exterior and interior photos of Secure Crisis Residential Centers in Clallam, Clark, and King Counties. Some youth have single rooms while others share a room with youth who have similar characteristics.

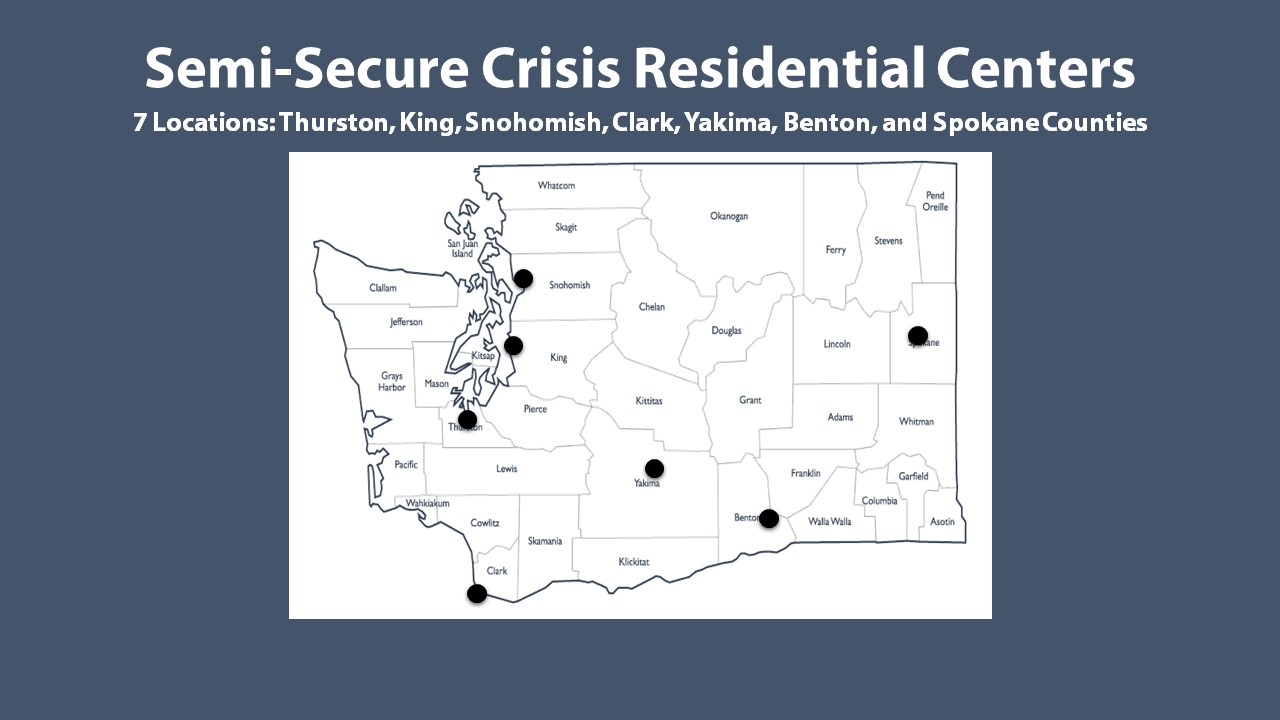

Semi-secure Crisis Residential Centers are offered in Thurston, King, Snohomish, Clark, Yakima, Benton, and Spokane Counties. There are 7 locations statewide, offering 45 beds.

Semi-secure Crisis Residential Centers offer housing and interventions for runaways and youth in conflict with their families. Semi-secure CRCs help youth reconcile with family or find other safe housing. Youth may leave these facilities during the day for appointments or to attend school.

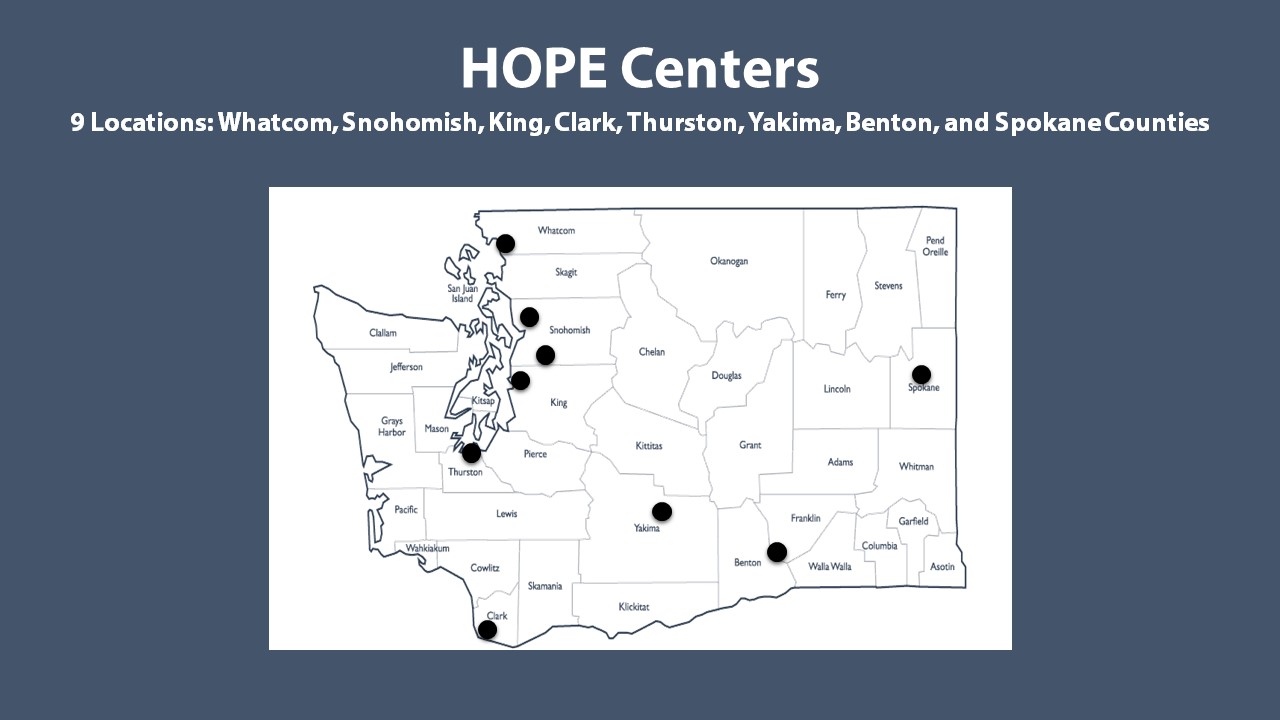

HOPE Centers are offered in Whatcom, Snohomish, King, Clark, Thurston, Yakima, Benton, and Spokane Counties. There are 9 locations offering 22 beds.

HOPE Centers provide housing, longer-term intervention, and more intensive case management. They help youth learn life skills and set personal goals and help youth reconcile with family or find other safe housing. Youth may leave these facilities during the day for appointments or to attend school.

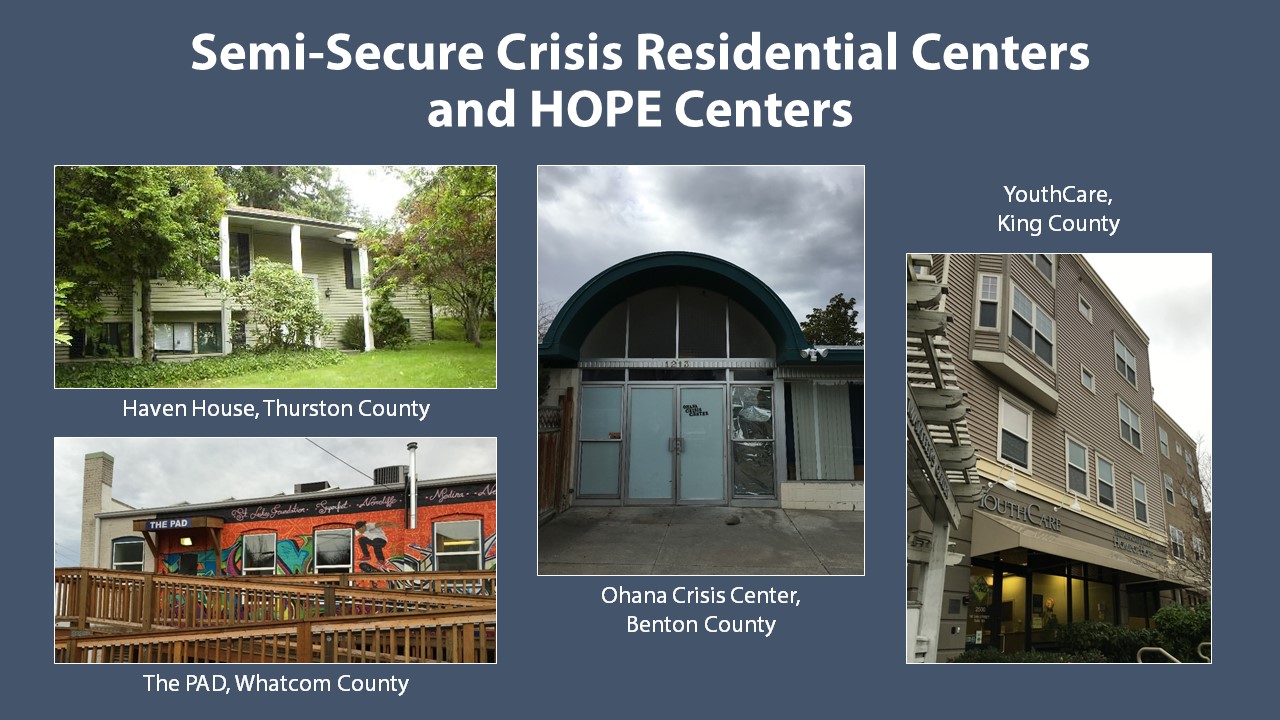

Semi-Secure Crisis Residential Centers and HOPE Centers are often located in the same facility. These are exterior photos of Semi-Secure Crisis Residential Centers and HOPE Centers in Thurston, Whatcom, Benton, and King Counties. Some are in urban areas while others are in residential neighborhoods.

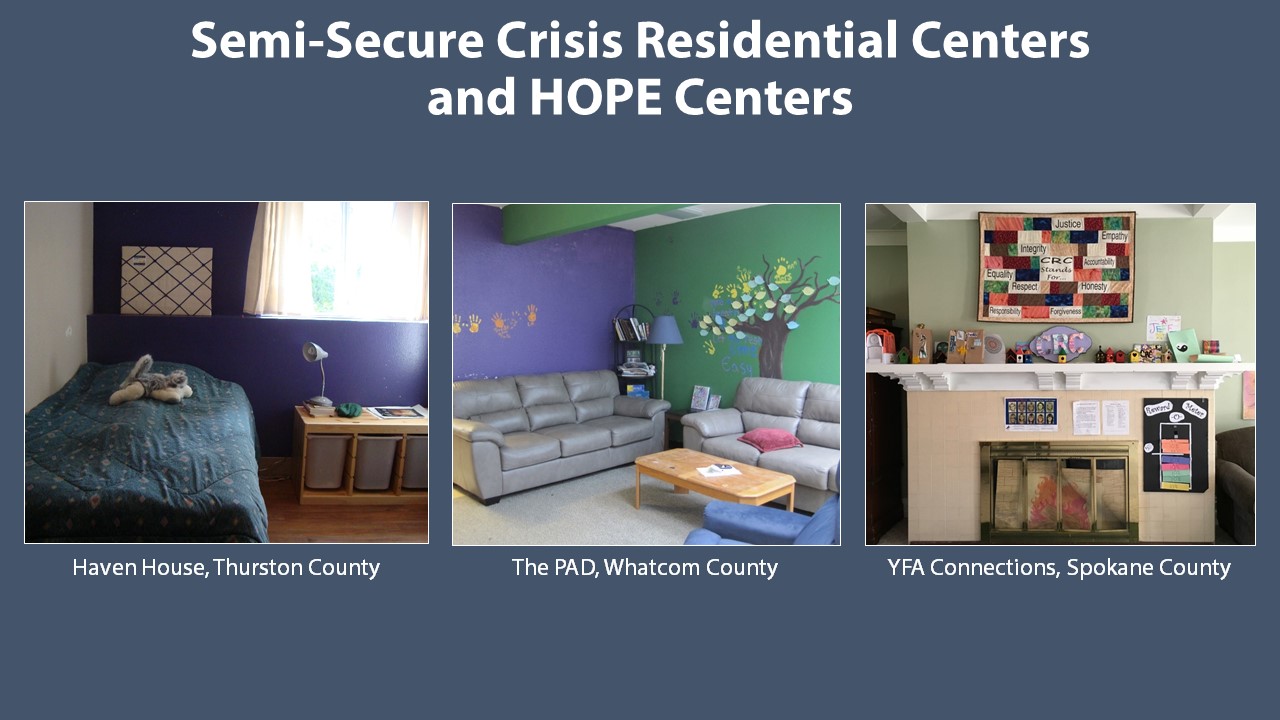

Many Semi-Secure Crisis Residential Centers and HOPE Centers aim to provide a home-like setting where youth can become comfortable with a structured environment (e.g., daily schedule with set times for meals, homework, and other activities). These are interior photos of Semi-Secure Crisis Residential Centers and HOPE Centers in Thurston, Whatcom, and King Counties.

Commerce can develop program-specific performance measures that reflect Legislative goals and are consistent with those used by other organizations

Download the appendix as a PDF

Federal programs, national organizations serving youth, and some state-contracted providers have performance measurement models in place for evaluating programs that serve unaccompanied homeless youth. The models include system-wide and program-specific measures to evaluate programs in four key areas: accessibility, quality, management, and outcomes. This is consistent with best practices for performance measurement.

Sample frameworks suggest core areas for performance measurement

Program-specific measures should reflect each program’s operations, purpose, short duration, and role in early or crisis intervention (Exhibit B).

JLARC staff developed sample performance measurement frameworks (Exhibits C and D) that align the measures used by other entities with Commerce’s statutory goals and program purposes.

- While not definitive, the frameworks suggest core performance measurement areas and indicators from which Commerce could develop specific measures.

- These sample measures are intended to be a foundation for developing program-specific measures and performance targets in consultation with the advisory committee and program providers.

- Commerce also could consider data availability and alignment with its other programs (e.g., transitional housing for young adults) in its measures.

| Measurement Area | Performance indicators |

|---|---|

| Accessibility | Number of youth served Program utilization rates Youth legal status Turn away rates |

| Quality | Number and percent of youth completing needs assessment |

| Management | Expenditure per youth served Expenditure per bed Lengths of stay |

| Outcomes (Statutory Goals) | |

| Stable housing | Number and percent of youth who: Exit to a safe and stable location, by destination (family, foster care, group home, transitional living, other program, treatment, detention) Return to program after exit Exit without permission (run away) |

| Permanent Connections | Number and percent of youth who: Complete service/case management plan Receive community support or participate in community activities Develop relationship with non-homeless peers, professionals, mainstream services |

| Education and Employment | Number and percent of youth who: Enroll in an education program Achieve education goals Complete education program Enroll in job training program/participate in related activity Obtain employment |

| Social and Emotional Well Being | Show improvement in some aspect of social/emotional well-being Participate in/complete substance abuse treatment Receive medical/mental health/dental care Participate in life skills development activities |

| Family Reconciliation | Number and percent of youth who: Receive Family Reconciliation Services referrals Reunite with family |

| Measurement Area | Performance indicators |

|---|---|

| Accessibility | Number of youth contacts, by contact location |

| Quality | Number of: Meals, hygiene, other supplies distributed Youth receiving service referrals |

| Management | Expenditure per youth served Number of contacts compared to staff size and homeless youth population |

| Outcomes (Statutory Goals) | |

| Stable housing | Number and percent of youth who: Receive referral to shelter or housing program, by program type (emergency shelter, short-term residential facility, transitional housing, permanent housing) |

| Permanent Connections | Number and percent of youth who: Enroll in case management Are new youth contacts Are repeat youth contacts |

| Education and Employment | Number and percent of youth who: Receive referrals to education/employment services |

| Social and Emotional Well Being | Number and percent of youth who: Receive service referrals or direct services, by service type (education, employment, medical, dental, substance abuse, mental health, family reconciliation, generic counseling, other) Receive basic needs services (food, clothing, supplies, hygiene) |

| Family Reconciliation | Number and percent of youth who: Receive Family Reconciliation Services referrals |

The Legislative Auditor makes three recommendations to improve data collection, grant management, and population estimates

Recommendation #1

Commerce should brief relevant legislative committees about how current consent law is interpreted, its effect on collecting data from homeless youth, and the potential impacts and trade-offs of collecting this data to evaluate program outcomes.

The Legislative goal of performance measurement and evaluation of youth outcomes appears to conflict with a Commerce legal interpretation that prevents prohibiting the inclusion of an unaccompanied homeless youth from consenting to include their personal data in HMIS.

Legislation Required |

No |

Fiscal Impact |

JLARC staff assume the briefings can be completed within existing resources. |

Implementation Date |

April 2017 |

Agency Response |

Recommendation #2

Commerce should develop program-specific performance measures. Commerce should incorporate performance measurement into grant agreements beginning in fiscal year 2018.

These measures should be based on the suggested performance measurement frameworks in Appendix 2 and should be developed with input from providers. Measures should include clearly defined program outputs (e.g. number of youth exiting the program to a particular destination), desired program outcomes (e.g. youth exiting to stable housing), and performance targets (e.g., at least 50% of youth exit the program to stable housing).

Legislation Required |

No |

Fiscal Impact |

JLARC staff assume measures and agreements can be developed within existing resources. |

Implementation Date |

June 2017 |

Agency Response |

Recommendation #3

Commerce and OSPI should issue joint guidance to counties and school districts, and clarify how they can work together to improve estimates of the unaccompanied homeless youth population.

The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and the U.S. Department of Education (ED) support collaboration between organizations serving homeless youth and school districts, within the limits of federal privacy laws.

Legislation Required |

No |

Fiscal Impact |

JLARC staff assume guidance can be issued within existing resources. |

Implementation Date |

December 2017 |

Agency Response |

Commerce and OSPI responded to Legislative Auditor recommendations

The Department of Commerce concurred with Legislative Auditor recommendations

The letter from Commerce is below. The agency concurred with the recommendations and suggested additional actions.

The Office of the Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI) partially concurred with the Legislative Auditor recommendation

The letter from OSPI is below. OSPI partially concurred with the recommendation that it issue joint guidance to counties and school districts and clarify how they can work together to improve estimates of the unaccompanied homeless youth population. It its letter, OSPI asked JLARC staff to clarify the recommendation.

Legislative Auditor comment on OSPI response

The intent of this recommendation is that the two agencies work together to clarify how counties and school districts can collaborate to improve the point-in-time counts coordinated by Commerce. As noted in this report, the U.S. Department of Education has distributed guidance that addresses such efforts. However, in interviews with individuals who conduct the counts, we learned there is confusion about the collaboration allowed. For example, interviewees reported that school districts had different ideas about what information could be shared and whether they could participate. We believe that OSPI is well-positioned to help inform school districts and reduce confusion.

DSHS and the Office of Financial Management did not comment

The Department of Social and Health Services (DSHS) and the Office of Financial Management (OFM) were given an opportunity to comment on this report. DSHS did not respond to this invitation, and OFM stated that it did not have comments.

Letters from Commerce and OSPI

Department of Commerce

Office of the Superintendent of Public Instruction

Audit Authority

The Joint Legislative Audit and Review Committee (JLARC) works to make state government operations more efficient and effective. The Committee is comprised of an equal number of House members and Senators, Democrats and Republicans.

JLARC's non-partisan staff auditors, under the direction of the Legislative Auditor, conduct performance audits, program evaluations, sunset reviews, and other analyses assigned by the Legislature and the Committee.

The statutory authority for JLARC, established in Chapter 44.28 RCW, requires the Legislative Auditor to ensure that JLARC studies are conducted in accordance with Generally Accepted Government Auditing Standards, as applicable to the scope of the audit. This study was conducted in accordance with those applicable standards. Those standards require auditors to plan and perform audits to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for findings and conclusions based on the audit objectives. The evidence obtained for this JLARC report provides a reasonable basis for the enclosed findings and conclusions, and any exceptions to the application of audit standards have been explicitly disclosed in the body of this report.

Committee Action to Distribute Report

On January 4, 2017 this report was approved for distribution by the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Committee.

Action to distribute this report does not imply the Committee agrees or disagrees with Legislative Auditor recommendations.

Scope & Objectives

Why a JLARC study of programs for unaccompanied homeless youth?

In 2015, the Legislature passed the Homeless Youth Prevention and Protection Act (2SSB 5404), which aims to coordinate statewide programs to reduce and prevent youth homelessness. The Act:

- Creates the Office of Homeless Youth Prevention and Protection Programs within the Department of Commerce (Commerce);

- Transfers some responsibilities from the Department of Social and Health Services (DSHS) to Commerce; and

- Directs the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Committee (JLARC) to review state-funded programs and services provided to unaccompanied homeless youth.

The Act also sets five priority service areas: stable housing, family reconciliation, permanent connections with adults, education and employment, and social and emotional well-being.

Who are unaccompanied homeless youth?

The Act defines unaccompanied homeless youth as persons under 18 years of age who lack a fixed nighttime residence and who are not in the physical custody of a parent or guardian. Local, state, federal, and non-profit entities may use a variety of other definitions for other purposes. For example, in other settings “youth” may include individuals between the ages of 18 and 24, and “homeless” may exclude individuals who stay temporarily in other people’s homes (“couch surfing”).

Programs and services include housing, support services, family reconciliation, and outreach

State-funded programs that serve unaccompanied homeless youth and other youth in crisis include the following:

- HOPE Centers and Crisis Residential Centers house youth for 5 to 30 days and provide counseling, health, education, and family reconciliation services.

- The Street Youth Services outreach program helps youth access health, housing, employment, and other support services.

Private organizations operate these programs under state contracts.

DSHS and Commerce will share responsibility

HOPE Centers, Crisis Residential Centers, and Street Youth Services were previously provided by DSHS. The Act transferred these programs from DSHS to Commerce. Commerce will now manage the programs and contracts, and DSHS will license the centers.

Study scope

The study will focus on youth under the age of 18. JLARC staff will report the estimates of Washington’s unaccompanied homeless youth population and the methods used to quantify this population.

The report will identify state-funded programs and services provided to unaccompanied homeless youth and review performance measures, data reliability, and reporting requirements. The study’s scope excludes programs that serve unaccompanied homeless youth as part of a broader population (e.g., food stamps).

JLARC staff will identify national practices and other appropriate standards regarding population estimates and performance measures for programs and services for homeless youth.

Study objectives

This study will address the following questions:

- How many unaccompanied homeless youth do agencies estimate there are in Washington, and what methods are used to make these estimates?

- What performance measures, reporting requirements, and data exist for state-funded programs and services provided to unaccompanied homeless youth?

- What national practices and other appropriate standards could inform the state’s approach to providing programs and services, and evaluating outcomes for unaccompanied homeless youth?

Timeframe for the study

Staff will present its preliminary report at the September 2016 JLARC meeting and the proposed final report at the December 2016 JLARC meeting.

Study methodology

The methodology JLARC staff use when conducting analyses is tailored to the scope of each study, but generally includes the following:

- Interviews with stakeholders, agency representatives, and other relevant organizations or individuals.

- Site visits to entities that are under review.

- Document reviews, including applicable laws and regulations, agency policies and procedures pertaining to study objectives, and published reports, audits or studies on relevant topics.

- Data analysis, which may include data collected by agencies and/or data compiled by JLARC staff. Data collection sometimes involves surveys or focus groups.

- Consultation with experts when warranted. JLARC staff consult with technical experts when necessary to plan our work, to obtain specialized analysis from experts in the field, and to verify results.

The methods used in this study were conducted in accordance with Generally Accepted Government Auditing Standards.

More details about specific methods related to individual study objectives are described in the body of the report under the report details tab or in technical appendices.

Contact

Authors of this Study

Rebecca Connolly, Research Analyst, 360-786-5175

Suzanna Pratt, Research Analyst, 360-786-5106

Valerie Whitener, Audit Coordinator

Keenan Konopaski, Legislative Auditor

Joint Legislative Audit and Review Committee

Eastside Plaza Building #4, 2nd Floor

1300 Quince Street SE

PO Box 40910

Olympia, WA 98504-0910

Phone: 360-786-5171

FAX: 360-786-5180

Email: JLARC@leg.wa.gov

JLARC Members on Publication Date

Senators

Randi Becker

John Braun, Chair

Sharon Brown

Annette Cleveland

David Frockt

Bob Hasegawa

Mark Mullet, Assistant Secretary

Representatives

Jake Fey

Larry Haler

Christine Kilduff

Drew MacEwen

Ed Orcutt, Secretary

Gerry Pollet

Derek Stanford, Vice Chair

Drew Stokesbary