Briefing Report: Student Mental Health Services Inventory (2016)

- Summary Information

- Multi-tiered Systems & Universal Supports

- Service Models

- Funding Sources

- Barriers to Services

- District Comments

- Education Service District

- Executive Summary

- Overview of Student Mental Health Services

- Medicaid-Funded Services

- About the Study

- Contacts

Executive Summary

At the Legislature’s request, staff of the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Committee (JLARC) inventoried mental health services available to students through schools, school districts, and educational service districts (ESDs). JLARC staff completed the inventory primarily through a survey of school districts, supplemented by interviews and analysis of existing data. The survey asked about what services are provided, who provides them, where they are provided, and who pays.

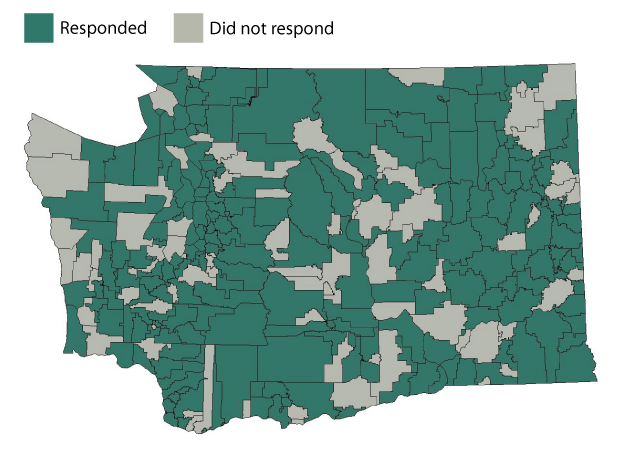

Three-quarters of school districts (218 of 295) completed the survey. The data in the inventory represent 85% of enrolled students and 83% of public schools (1,985 of 2,392) in Washington.

This report includes both summary information as well as topic-specific tables. Readers can sort, filter, and review the data presented in the tabs above. Readers also can download the complete data file for schools, school districts, or ESDs.

Inventory highlights

- 191 districts report that some or all of their schools have a basic level of mental health services that focuses on prevention and promoting positive behaviors (65% of all districts).

- Districts report that screening for mental health concerns occurs in 1,844 schools (77% of all schools).

- Districts report that students receive mental health services, such as therapies, in their communities and in schools:

- At 1,411 schools, services are provided in the community (59% of all schools).

- At 796 schools, services are provided in the school by a community provider (33% of all schools).

- At 448 schools, services are provided in the school by a district or ESD employee (19% of all schools).

- Districts report that funding comes from a variety of sources, regardless of where service is provided:

- Private insurance funds services for students at 942 schools (39% of all schools).

- Medicaid funds services for students at 863 schools (36% of all schools).

- Other: Levy dollars fund services for students at 240 schools and dedicated county sales taxes fund services for students at 221 schools.

- Districts report that students experience various barriers to accessing mental health services. Barriers include transportation, lack of providers, and affordability of private insurance co-pays.

Medicaid funds some school-based mental health services

In 2015, of the 1.1 million students in public schools, 55,000 (5%) received Medicaid-funded mental health services. Most of these students were served outside their schools through managed care plans and publicly-funded mental health and substance abuse treatment centers. Approximately 10,000 of the students (1%) received Medicaid-funded mental health services in their schools. School districts receive reimbursement from Medicaid for certain services through contracts with the Health Care Authority.

Access the inventory

The information in the inventory can be found by clicking on the top tabs. Please allow a moment or two for the data to load.

- The Multi-tiered Systems & Universal Supports tab contains information about universal supports and multi-tiered systems of support.

- The Service Models tab contains information about students’ access to services, screening, and where services are provided.

- The Funding Sources tab contains information about sources of mental health care funding.

- The Barriers to Services tab contains data about barriers to accessing mental health services.

- The District Comments tab contains additional input from districts regarding mental health services for students in their district.

- The Educational Service District tab contains results from the survey of educational service districts.

Overview of Student Mental Health Services

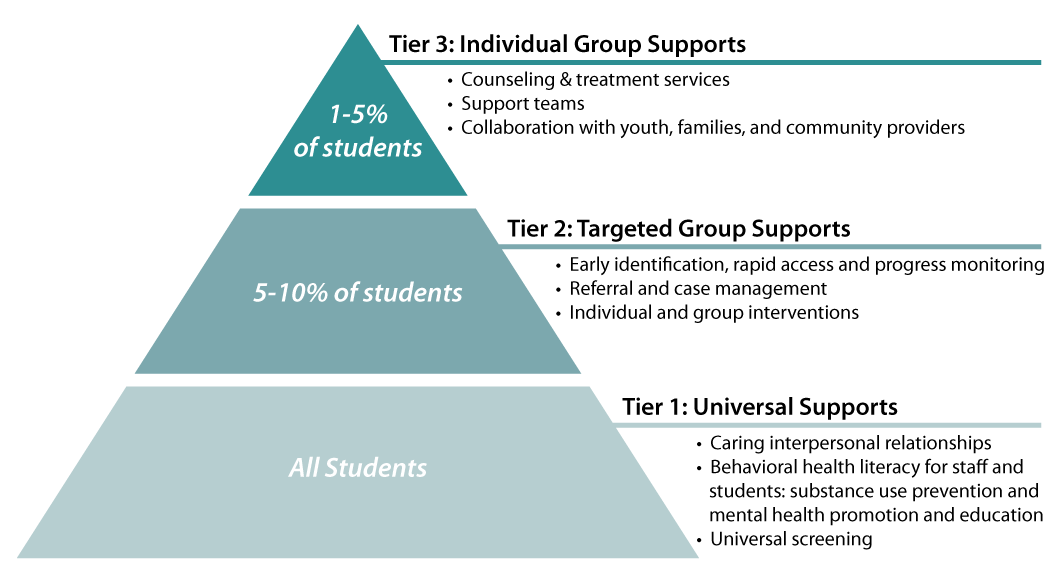

The Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI) has identified a multi-tiered system of support as a best practice for behavioral supports and mental health services. According to OSPI, the goal of the multi-tiered system is to integrate mental health services into a student’s academic instruction.

Universal supports are the first tier of a multi-tiered system. They are focused on prevention by promoting desired behavior. For example, a school may expect that all students “Respect Yourself, Others, and Property.” Universal supports are intended to create an environment conducive to learning and to promote positive behaviors. Staff members are to provide these supports to every student.

Tiers 2 and 3 involve referrals and more direct mental health services such as support groups or individual counseling.

For Tier 1, JLARC staff collected data about the use and types of universal supports provided in schools. For Tiers 2 and 3, JLARC staff collected information about screening, referrals, and services, and also identified where and by whom services are provided. Below are some highlights from the survey about multi-tiered systems and universal supports, as well as approaches to serving students in the community or directly in the schools.

Multi-tiered systems & universal supports

Districts were asked about multi-tiered systems of support and universal supports.

- 191 districts report that some or all of their schools have universal supports.

- 178 districts report that some or all of their staff are trained in multi-tiered systems of support.

- 126 districts report that the multi-tiered system of support used in some or all of their schools is the Positive Behavior Intervention and Support (PBIS) model. Some use PBIS only in special education classrooms. PBIS is one specific approach for implementing multi-tiered support, which focuses on creating a positive environment for learning and meeting student needs.

Referral to community providers

Some districts screen for mental health concerns. They report that if a need is identified, a referral to a community mental health provider is often made. The schools do not have licensed mental health professionals on staff or available from the district, and community providers do not come to the schools. Districts report that:

- 1,844 schools have staff, typically guidance counselors, teachers, and school nurses, who screen for mental health concerns.

- Students in 1,411 schools receive mental health services, such as therapies and counseling, from providers in the community.

In-school services

In some schools, after screening, students with identified needs are provided mental health services in their schools. These schools use a variety of approaches, such as:

- Employing mental health therapists to conduct assessments, develop plans, provide crisis intervention, and make referrals.

- Partnering with community health organizations to offer school-based health centers in middle and high schools where students receive therapy and counseling.

- Becoming a licensed mental health center with therapists on staff to provide group therapy and counseling.

Districts with these schools report that:

- Community providers serve students in 796 schools.

- Districts and educational service district (ESD) staff provide services in 448 schools.

Notable in-school service models used in Washington schools

The Legislature asked JLARC staff to identify models of mental health services that are integrated into schools. Interviews with mental health professionals, OSPI staff and academics identified four such examples:

- Project Aware (Advancing Wellness and Resilience in Education): Three school districts (Shelton, Battle Ground, and Marysville) have partnered with OSPI on a 5-year, $10 million federal grant to increase awareness of mental health issues among school-aged youth and to improve access to services. School-based mental health services are provided through collaborations with ESDs and community-based providers. Additionally, the Project provides training in mental health for school personnel, families and community members.

- Project Prevention: Funded by a federal grant, Educational Service District 101 Northeast employs eight mental health therapists. The therapists work in 15 schools providing therapy and counseling to students in four school districts (Cheney, Medical Lake, Riverside, and West Valley). The therapists assess students and coordinate teams that develop plans for individual students. The therapists also provide crisis intervention and stress management services. They work with both students and families to promote services, make referrals to community resources, and provide parent education.

- School Based Health Centers: Seattle Public Schools has partnered with community health organizations to have School-Based Health Centers (SBHCs) located in 64 of its middle and high schools. The SBHCs are operated by community health agencies. The centers evaluate and treat common health problems including mental health. They provide individual and group therapy and counseling for depression, trauma, stress, and problem-solving. The SBHCs are funded with city levy dollars, Medicaid, private insurance, and contributions from the sponsoring agencies. These services are also available in eight elementary and K-8 schools.

- Spokane Public Schools: Spokane Public Schools contracts with the Spokane County Behavioral Health Organization (BHO) to be a licensed mental health center. It is the only district that JLARC staff found licensed this way. As a licensed mental health center, the district qualifies to receive Medicaid funds. The district employs 50 therapists who have offices in schools where they can provide group therapy and individual counseling. Each high school has at least one therapist. Therapists are located in 45 out of 52 of the Spokane schools. Contracting with the BHO allows Spokane to work with the entire public mental health system. Spokane now contracts with the Mead and Central Valley school districts and has five therapists located in those districts.

Medicaid-Funded Services

There are 1.1 million public school students in Washington. In 2015, the Health Care Authority (HCA) estimates that about 55,000 students (5%) ages 5 through 17 received Medicaid-funded (Apple Health) mental health services. Most of these students were provided services outside of a school setting through managed care plans and publicly-funded mental health and substance abuse treatment centers known as Behavioral Health Organizations (BHOs). Approximately 10,000 students – 1 percent of all students – received Medicaid-funded mental health services in their schools.

Districts are eligible to receive Medicaid reimbursement for services provided, but few do

HCA contracts with 211 school districts to receive fee-for-service Medicaid reimbursement to provide medically necessary services. Counseling and psychological assessments are included in the covered services if provided by a qualified professional to a student as part of their Individualized Education Program (IEP) or Individualized Family Service Plan (IFSP).

HCA notes that many school districts report not having qualified staff to meet program requirements for billing Medicaid. In fact, according to HCA, only 4 of the 211 contracted school districts consistently bill Medicaid for mental health services.

A recent clarification by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) related to reimbursement may make it easier for districts and educational service districts (ESDs) to seek Medicaid reimbursement. The clarification allows districts and ESDs that contract with HCA to seek reimbursement for services provided to Medicaid-enrolled students even if other students are not charged for the same services.

Some districts also receive reimbursement for helping students and families access Medicaid

ESD 113 Capital Region and 37 school districts use the Medicaid Administrative Claiming program. They receive Medicaid reimbursement for helping students and their families learn about Apple Health (Medicaid), enroll in the program, and access services.

Study background and methodology

The 2016 Legislature passed E2SHB 2439 with a stated intent to improve access to adequate, appropriate, and culturally responsive mental health services for children and youth. The legislation directed the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Committee (JLARC) to inventory mental health services available to students through schools, school districts, and educational service districts (ESDs).

Methodology

JLARC staff was directed to use only data that is already collected by schools, school districts, and ESDs. Staff could not and did not collect or review student-level data.

Interviews and Surveys: JLARC staff interviewed staff from the Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI), ESDs, and school districts. JLARC staff learned that the inventory could not be completed with existing data due to a lack of information about current services. JLARC staff designed surveys in order to collect information requested by the Legislature.

School District Survey: JLARC staff worked with mental and behavioral health experts and staff from OSPI, ESDs, and school districts to develop and test school district survey questions. The Social and Economic Sciences Research Center (SESRC) at Washington State University conducted the survey between July and September 2016. Up to nine contacts (including letters, emails, postcards, and phone calls) were made to districts to encourage survey completion.

Overall, 218 school districts (74%) completed or partially completed the survey. The districts that responded include 85% of enrolled students and 83% of public schools (1,985 of 2,392).

Survey responses were compiled into an inventory of student mental health services. Readers can sort, filter, and review the data presented in the tabs above. Readers also can download the complete data files for schools, school districts and ESDs. In this report, the inventory is divided into five separate data sets based on different topics covered in the surveys. JLARC staff included additional information on districts and schools from the OSPI website to allow for more detailed sorting and analysis (Exhibit 2).

Exhibit 2: Information included in the Mental Health Services Inventory Report Tabs

| Topic/Tab | District or School-Level Information? | Additional Detail Included |

|---|---|---|

| School |

|

|

| School | ||

| District |

|

|

| District | ||

| District |

Educational Service District Survey: JLARC staff surveyed ESD prevention directors and student support administrators. Questions focused on trainings offered to district staff and mental health services provided to students by ESDs. Seven of the nine ESDs responded to the survey. The non-responding ESDs were ESD 121 Pasco and ESD 171 North Central. Readers can review the data presented in the tab above and download the complete data file for ESDs.

Contacts

Authors of this Study

John Bowden, Research Analyst, 360-786-5298

Eric Thomas, Research Analyst, 360-786-5182

Project Supervisor: John Woolley, 360-786-5184

Keenan Konopaski, Legislative Auditor

Joint Legislative Audit and Review Committee

Eastside Plaza Building #4, 2nd Floor

1300 Quince Street SE

PO Box 40910

Olympia, WA 98504-0910

Phone: 360-786-5171

FAX: 360-786-5180

Email: JLARC@leg.wa.gov

Key takeaways about prevention models and student supports

This table presents results from survey questions about universal supports and multi-tiered systems of support. Three-quarters of school districts (218 of 295) completed the survey. The data represent 85% of enrolled students and 83% of public schools (1,985 of 2,392) in Washington.

How many schools offer a basic level of mental health services and support?

- 191 districts report having universal supports in some or all schools. Universal supports are the foundation of a multi-tiered system. They are designed to prevent and identify mental health issues for all students (see Overview of Student Mental Health Services).

- 178 districts report that staff in some or all schools are trained in multi-tiered systems of support. A multi-tiered system integrates mental health services into a student’s academic instruction and support. Training helps staff identify students whose needs exceed the universal behavioral supports.

Who screens students for mental health concerns?

Districts report that screening for mental health concerns occurs in 1,844 schools. Many different staff members may screen students at each school.

- Guidance counselors conduct screenings in 1,327 schools.

- Other staff include psychologists (857 schools), school nurses (771 schools), teachers (646 schools), and social workers (348 schools).

Using the table

- Scroll the spreadsheet window to the right to view all columns.

- Use the drop down arrows in the column headings and click “Filter” to select results for specific school district characteristics or types of survey responses.

- To filter by Legislative district, click the dropdown arrow and enter the two-digit numeric district code into the “search” window (e.g., District 2 = “02”).

Key takeaways about services provided to students

This table presents results from survey questions about students’ access to services, screening, and where services are provided. Three-quarters of school districts (218 of 295) completed the survey. The data represent 85% of enrolled students and 83% of public schools (1,985 of 2,392) in Washington.

Can students access services?

Districts report that:

- 1,336 schools have limited access to direct mental health services (e.g., therapy and intervention).

- 369 schools have adequate access.

- 177 have no access to services.

Who provides services?

Schools may have both community-based providers and providers in schools. Districts report that:

- In 1,411 schools, direct mental health services are provided in the community.

- In 796 schools, services are provided in schools by a community provider.

- In 448 schools, services are provided in schools by a district or ESD employee.

What information do schools have?

Districts reported that 823 schools receive information from providers, within limits of federal law, about students who access services to ensure coordination of care with their education.

Using the table

- Scroll the spreadsheet window to the right to view all columns.

- Use the dropdown arrows in the column headings to filter the data by school characteristics and survey responses.

- “N/A” means that the data was not included in OSPI’s public dataset.

Key takeaways about funding for mental health services

This table presents results from survey questions about sources of mental health care funding. Three-quarters of school districts (218 of 295) completed the survey. The data represent 85% of enrolled students and 83% of public schools (1,985 of 2,392) in Washington.

What are the common funding sources?

Districts reported how the mental health services for students are funded, regardless of where the services are provided. Districts did not report total amounts spent. Districts report that:

- Private insurance funds services for students at 942 schools.

- Medicaid funds services for students at 863 schools.

Other sources include levy dollars (240 schools) and dedicated county sales taxes (221 schools). The county sales tax is 1/10th of 1 percent as authorized by RCW 82.14.460.

Using the table

- Scroll the spreadsheet window to the right to view all columns.

- Use the dropdown arrows in the column headings to filter the data by school characteristics and survey responses.

- “N/A” means that the data was not included in OSPI’s public dataset.

Key takeaways about barriers to accessing services

This table presents results from survey questions about barriers to accessing mental health services. Three-quarters of school districts (218 of 295) completed the survey. The data represent 85% of enrolled students and 83% of public schools (1,985 of 2,392) in Washington.

Are there barriers to accessing services?

203 districts report that students experience barriers to accessing direct mental health services (e.g., therapy, interventions).

What are the barriers?

The survey asked districts to identify specific barriers and allowed respondents to choose more than one.

- 159 districts report a lack of transportation.

- 156 districts report a lack of providers within an hour's drive of school.

- 122 districts report that private insurance co-payments are too high.

Do barriers differ between urban and rural districts?

- 56 urban districts report a lack of transportation as a barrier, followed by private insurance co-payments that are too high (51) and a lack of providers within an hour’s drive (47).

- 109 rural districts report lack of providers as a barrier, followed by lack of transportation (103) and high private insurance co-payments (71).

Using the table

- Scroll the spreadsheet window to the right to view all columns.

- Use the drop down arrows in the column headings and click “Filter” to select results for specific school district characteristics or types of survey responses.

- To filter by Legislative district, click the drop down arrow and enter the two-digit numeric district code into the “search” window (e.g., District 2 = “02”).

Comments from districts offer additional insights

Of the 218 school districts that responded to the survey, 136 provided comments related to mental health services for students.

This table presents comments from school districts about the mental health services that are available to students in the district.

- Scroll the spreadsheet window to the right to view all columns.

- Use the drop down arrows in the column headings and click “Filter” to select results for specific school district characteristics or types of survey responses.

- To filter by Legislative district, click the drop down arrow and enter the two-digit numeric district code into the “search” window (e.g., District 2 = “02”).

Key takeaways from survey of educational service districts

Seven of the state’s nine ESDs responded to the JLARC staff survey. This table presents results from the ESD survey.

What steps did the ESDs report taking?

All seven of the responding ESDs:

- Offer training to districts and schools to recognize mental health needs;

- Provide referrals to connect students to community mental health services;

- Work with local health districts and publicly-funded Behavioral Health Networks; and

- Have successfully applied for mental health grants (including Project AWARE).

How many mental health professionals are on staff?

The number of mental health professionals employed by each ESD ranged from 0 to 9 staff members.

Are any of the ESDs licensed mental health providers?

Only ESD 113 Capital Region reports that the ESD itself is a licensed mental health provider. It reports that this status allows it to implement comprehensive school-based behavioral health programs in pilot locations. ESD 112 Vancouver is exploring this option, and ESD 114 Olympic reports recently closing its program due to numerous barriers.

Are there pilot projects?

Three ESDs reported that mental health pilot projects are currently underway.

Using the table

- Scroll the spreadsheet window to the right to view all columns.

Updated on 11/8/16. Previous version incorrectly stated ESD 114 Olympic recently closed its licensed mental health program: this now reads ESD 189 Northwest recently closed its program.