JLARC Final Report: 2015 Tax Preference Performance Reviews

Report 15-5, January 2016

Motion Picture Program Contributions | B&O Tax

- Summary of this Review

- Details on this Preference

- Recommendations and Agency Response

- How We Do Reviews

- More about this Review

| The Preference Provides | Tax Type | Est. Beneficiary Savings in 2015-17 Biennium |

|---|---|---|

| A business and occupation (B&O) tax credit equal to the amount of contributions made to the Washington Motion Picture Competitiveness Program. | B&O RCWs 82.04.4489; 43.365.020 |

$7 million |

| Public Policy Objective |

|---|

The Legislature stated two public policy objectives:

|

| Recommendations |

|---|

Legislative Auditor’s Recommendation: Review and Clarify To provide additional detail on the target for Washington’s film industry relative to other states, as well as desired employment outcomes for jobs, average hourly wages, and health and benefits coverage. Commissioner Recommendation: The Commission endorses the Legislative Auditor’s recommendation without comment. |

- What is the Preference?

- Legal History

- Other Relevant Background

- Public Policy Objectives

- Are Objectives Being Met?

- Beneficiaries

- Revenue and Economic Impacts

- Technical Appendix

- Other States with Similar Preference?

- Applicable Statutes

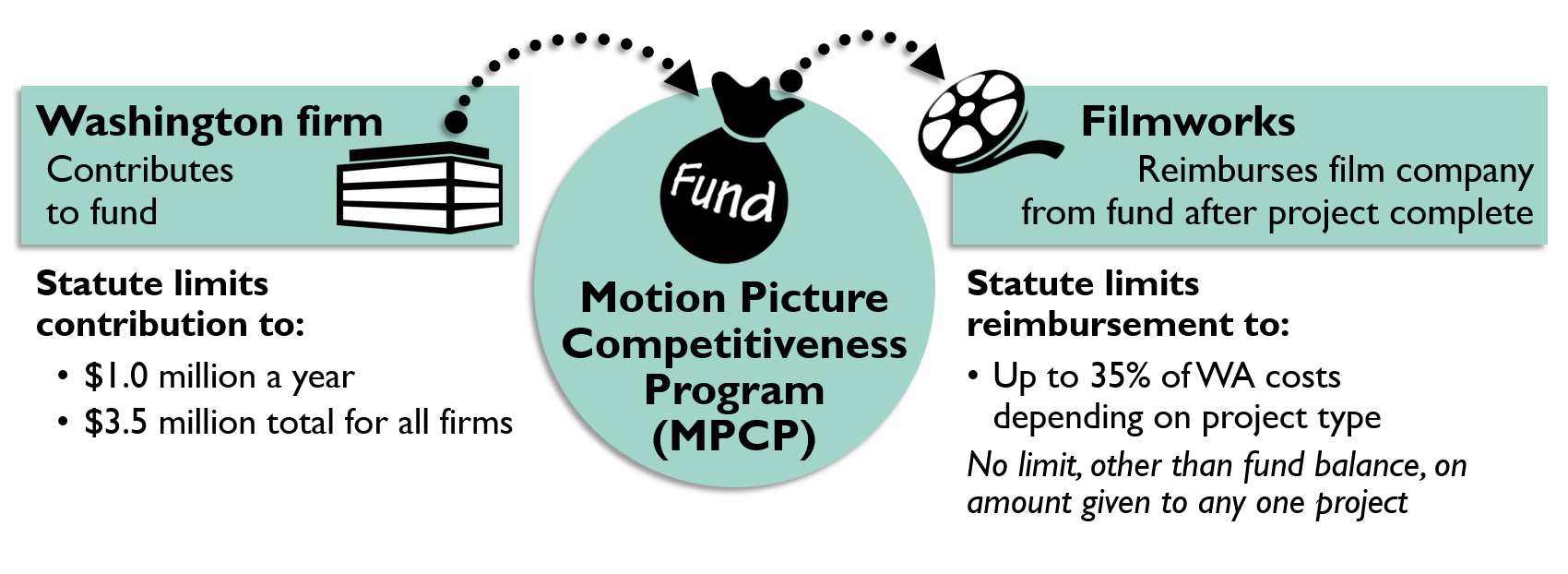

Businesses may claim a credit against their business and occupation (B&O) tax equal to the amount of contributions they make to the Washington Motion Picture Competitiveness Program (MPCP). The MPCP reimburses motion picture companies for their qualifying expenses in Washington with these contributions. There are two types of beneficiaries considered in this tax preference review:

- The businesses with Washington tax liability that make contributions to the MPCP; and

- The businesses producing motion pictures in Washington that benefit from the funding assistance provided by the MPCP.

The Washington Business Contributors

The annual amount of B&O tax credit for any one contributor is capped at $1 million a year. The total cap for all contributions is $3.5 million a year. Contributors include businesses such as banks, hotels, and restaurants. A business may carry over unused credit to use against its tax liability for three succeeding years after the year it made the contribution, but it may not exceed the credit maximum of $1 million a year. No credit may be earned for contributions made after June 30, 2017.

The Motion Picture Production Projects

The MPCP uses the businesses’ contributions to provide assistance to motion picture projects for costs incurred in Washington. Motion picture businesses apply to the program for assistance before beginning production. Washington Filmworks, the nonprofit organization that manages the program, reimburses feature films, episodic series, and commercials after completion of the project. Reimbursement covers up to 35 percent of their Washington costs. Except for the available fund balance, there is no limit on the amount given to any one project.

Exhibit 1 below shows the flow of contributions into the MPCP fund and the reimbursements to film companies out of the fund.

Statute sets the broad criteria for selecting motion picture projects and establishes the funding levels and required investment minimums for different types of projects, including feature films, episodic series, and commercials. The law allows more restrictive criteria to be established by the Department of Commerce (Commerce) or by the Governor-appointed board of directors of the MPCP.

The Legislature requires consideration for approval be given to, among other factors:

- The additional income and tax revenue to be retained in the state for general purposes;

- The creation and retention of family wage jobs that provide health and retirement benefits;

- The impact on maximizing in-state labor and the use of in-state production and post-production companies; and

- The impact on the state and local economy, including multiplier effects.

Additional Requirements

According to statute, the percentage of reimbursement varies from 30 percent to 35 percent of eligible costs depending on the type of project. Non-resident labor costs are reimbursed at 15 percent if at least 85 percent of the workforce are Washington residents. Washington Filmworks guidelines further define labor eligibility requirements and reimbursement criteria for feature films, episodic series, and commercials. For example, statute allows reimbursement up to 30 percent of qualifying expenses for commercial applicants but Filmworks guidelines limit reimbursement to between 15 percent and 25 percent of their in-state production costs.

Statute also allows for up to 10 percent of the annual funding to support the Innovation Lab, a new program designed for Washington filmmakers using new forms of production and emerging technologies. Washington Filmworks guidelines outline the eligibility requirements and per-project reimbursement rates of Innovation Lab funded projects. All projects receiving reimbursement through the MPCP must meet a minimum investment requirement. See Exhibit 2 below.

| Type of Project | Minimum WA Project Investment At Least: | Maximum Statutory Reimbursement |

|---|---|---|

| Feature films | $500,000 | 30% of WA costs |

| Episodic series – 6 or more | $300,000 per episode | 35% of WA costs |

| Episodic series –Fewer than 6 | $300,000 per episode | 30% of WA costs |

| Commercials associated with a national or regional campaign | $150,000 | 30% of WA costs |

| WA filmmakers using new forms of production or emerging technologies (Innovation Lab) | $25,000 | N/A |

Motion picture businesses must report to Commerce on a survey following the completion of each funded project and before receiving reimbursement. The survey asks beneficiaries for the amount of taxes paid in Washington broken down by type of tax, the amount of qualified expenditures and amount of reimbursement received, and detailed information on the number of employees, their hours, wages, and benefits. Commerce must report annual descriptive statistics to the Legislature by September of each even-numbered year.

Commerce and MPCP Requirements

Qualified expenditures are listed in Commerce’s rules and in the MPCP guidelines. They include food and lodging, set construction, wardrobe, production services such as photography and sound synchronization, rental of equipment and vehicles, and compensation to Washington residents and certain non-residents. News, talk shows, sports events, political advertising and video games are not eligible for funding assistance.

Motion picture businesses are also eligible for sales and use tax exemptions under a different tax preference. That preference is for rental of production equipment and production services. Equipment includes grip and lighting equipment, cameras, camera mounts, and motor vehicles. Production services include motion picture and video processing, printing, editing, duplicating, animation, graphics, special effects, and sound effects. This tax preference was included in JLARC’s 2014 expedited review.

2006

The Legislature enacted the Motion Picture Competitiveness Program (MPCP) and the B&O tax credit for contributors to the program. No credits could be earned for contributions made after June 30, 2011.

The program reimbursed film projects at 20 percent of their Washington costs, and no one project could receive more than $1 million. The Legislature set the minimum investment requirements for feature films at $500,000 and episodes at $300,000, the same as current levels. Commercial projects were required to invest at least $250,000 in Washington to be eligible.

The legislation also required JLARC to report to the legislative fiscal committees by December 2010 on the effectiveness of the program.

2008

The Legislature made changes to the incentive statute, including eliminating the $1 million-per-production cap and decreasing the investment requirement for commercials from $250,000 to $150,000.

2009

The Legislature increased the maximum reimbursement from 20 percent to 30 percent of the company’s in-state costs. The higher funding level went into effect April 15, 2009.

2010

JLARC staff conducted a performance review of the Motion Picture Competitiveness Program as required in the 2006 legislation. The Legislative Auditor made two recommendations:

- “Because Washington has maintained its position as a competitive location for filming, the Legislature should continue this preference and reexamine the preference at a later date to determine its ongoing effectiveness in encouraging filming in Washington.”

- “If the Legislature desires information on the revenue and economic impacts of the tax credit, it should require more stringent reporting and clarify what entity is responsible for maintaining the information.” The report noted some difficulties in determining types of taxes paid and full-time versus part-time employment from the Commerce Survey.

2011

The credit for motion picture contributions expired June 30, 2011.

2012

The Legislature re-enacted the motion picture credit to apply to contributions made between June 7, 2012 and June 30, 2017. Businesses claimed $3.5 million in both Calendar Years 2011 and 2012, despite the incentive not being in place for a year after expiring in June 2011.

In addition, the 2012 legislation:

- Increased the maximum reimbursement for producers of episodic series of six or more episodes to 35 percent;

- Provided reimbursement for non-resident crew members of up to 15 percent of their compensation if at least 85 percent of the employees are Washington residents (previously, only resident compensation was reimbursed);

- Allowed up to 10 percent of annual funding to support Washington filmmakers, new forms of production, and emerging technologies; and

- Addressed the 2010 JLARC study findings by requiring motion picture companies to report more detail on taxes and employment to Commerce.

Entities Responsible for Administering and Managing the MPCP

The Motion Picture Competitiveness Program (MPCP) is administered by a nine-member board of directors appointed by the Governor, and managed by a non-profit organization, Washington Filmworks. Members of the board represent the motion picture production industry, the interactive media or emerging technology industry, labor unions, visitors and convention bureaus, and travel-related industries. The board is involved in aspects such as developing program guidelines, approving completion package requirements, approving which motion picture projects are to receive funding, and providing fiscal oversight for the program.

The motion picture companies benefiting from state reimbursement have received $22.6 million over the life of the program for qualifying investments of $85.4 million. A total of 96 projects have received assistance over the same eight years. Reimbursements are not limited by the amount of contributions, but by the balance in the MPCP fund. While MPCP may collect $3.5 million in a given year, it does not need to disperse the full amount in that year. See Exhibit 3 below.

FYs 2007-2014

| Fiscal Year | Number Completed Projects |

Qualified Project Spending |

State Reimbursement Paid |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | 2 | $1,047,031 | $203,665 |

| 2008 | 8 | $6,704,051 | $1,337,810 |

| 2009 | 14 | $15,808,957 | $3,205,607 |

| 2010 | 16 | $18,387,627 | $5,516,288 |

| 2011 | 22 | $13,465,933 | $3,992,689 |

| 2012 | 9 | $10,899,713 | $3,119,780 |

| 2013 | 14 | $9,435,555 | $2,570,383 |

| 2014 | 11 | $9,688,254 | $2,649,530 |

| Total | 96 | $85,437,121 | $22,595,752 |

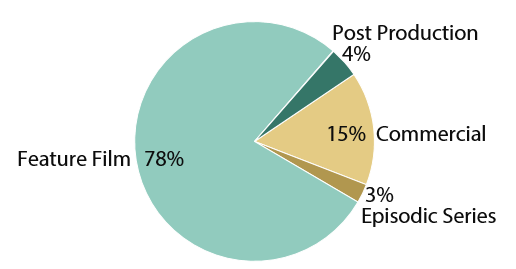

For the years 2009 to 2014, feature film projects have consistently received the largest share of the available funding from the MPCP.

What are the public policy objectives that provide a justification for the tax preference? Is there any documentation on the purpose or intent of the tax preference?

The Legislature stated two public policy objectives in the 2006 statute:

1. To regain and revitalize Washington’s competitive position both nationally and internationally.

Bill language indicated the Legislature’s commitment to “leveling the competitive playing field” in recognition of national and international competition and its interest in regaining “Washington’s place as a premier destination to make motion pictures, television, and television commercials.”

In addition, the Legislature required Commerce to establish criteria for the Motion Picture Competitiveness Program (MPCP) “with the sole purpose of revitalizing the state’s economic, cultural, and educational standing in the national and international market of motion picture production.”

2. To provide family wage jobs with health and retirement benefits.

The Legislature expressed a finding that Washington workers are increasingly without health and retirement benefits, causing “hardships on workers and their families and higher costs to the state.” In selecting projects to be funded, the Legislature required that consideration be given to the creation of family wage jobs that provide health and retirement benefits and the impact of the project to maximize in-state labor and the use of in-state production companies.

What evidence exists to show that the tax preference has contributed to the achievement of any of these public policy objectives?

1. Regain and Revitalize Washington’s Competitive Position

Evidence is inconclusive regarding whether Washington is regaining and revitalizing its competitive position.

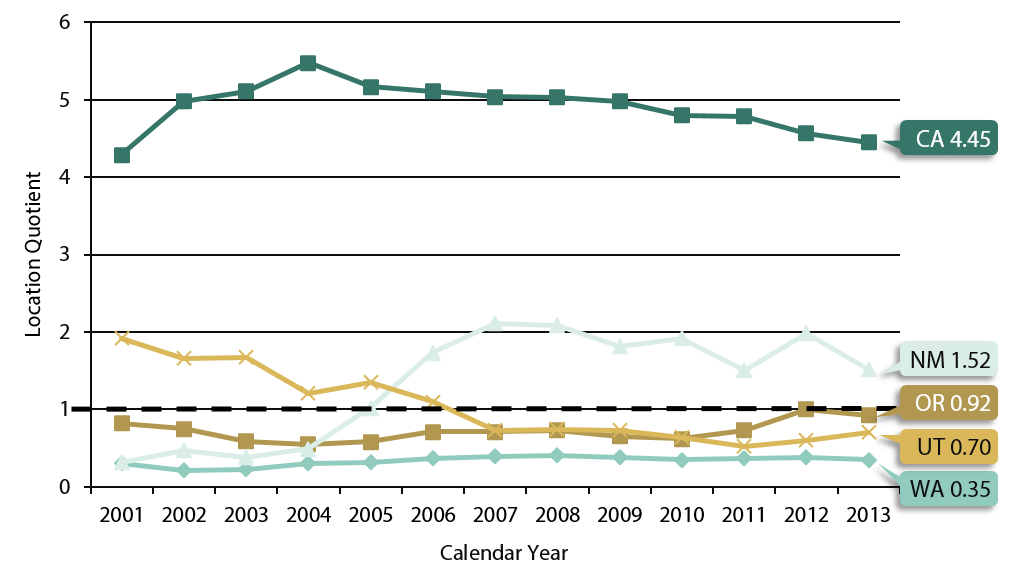

JLARC staff analyzed Washington’s competitive position by measuring employment concentration using federal Bureau of Labor Statistics location quotients. Location quotients compare a state’s share of employment in an industry to the total national share of employment in that industry. A location quotient of 1.0 means an industry is equally concentrated in the state as in the nation. Location quotients are available for the motion picture industry which is representative of companies qualifying for Motion Picture Competitiveness Program (MPCP) funding.

Exhibit 4 below shows that Washington’s motion picture location quotient is lower than the national average of 1.0 and lower than other western states with motion picture incentives. Location quotients are not available for other countries.

Exhibit 5 below shows that Washington ranks 14th (the top third) of the states in its concentration of motion picture industry employment. California ranks first, and New York ranks second.

| State | Location Quotient | Location Quotient Rank |

Motion Picture Tax Preference |

|---|---|---|---|

| California | 4.45 | 1 | Yes |

| New York | 3.35 | 2 | Yes |

| Louisiana | 1.88 | 3 | Yes |

| New Mexico | 1.52 | 4 | Yes |

| Hawaii | 1.22 | 5 | Yes |

| Connecticut | 1.07 | 6 | Yes |

| Oregon | 0.92 | 7 | Yes |

| Utah | 0.70 | 8 | Yes |

| Georgia | 0.63 | 9 | Yes |

| Nevada | 0.61 | 10 | Yes |

| Massachusetts | 0.51 | 11 | Yes |

| New Jersey | 0.46 | 12 | Yes |

| Tennessee | 0.38 | 13 | Yes |

| Washington | 0.35 | 14 | Yes |

| Florida | 0.34 | 15 | Yes |

| Colorado | 0.34 | 16 | Yes |

| Pennsylvania | 0.33 | 17 | Yes |

| Montana | 0.33 | 18 | Yes |

| Maryland | 0.33 | 19 | Yes |

| Virginia | 0.26 | 20 | Yes |

| Texas | 0.26 | 21 | Yes |

| Rhode Island | 0.24 | 22 | Yes |

| Michigan | 0.24 | 23 | Yes |

| Illinois | 0.20 | 24 | Yes |

| Minnesota | 0.19 | 25 | Yes |

| South Dakota | 0.18 | 26 | No |

| Vermont | 0.17 | 27 | No |

| New Hampshire | 0.17 | 28 | No |

| South Carolina | 0.16 | 29 | Yes |

| Wisconsin | 0.14 | 30 | No |

| Ohio | 0.14 | 31 | Yes |

| North Carolina | 0.14 | 32 | Yes |

| Missouri | 0.13 | 33 | No |

| Arizona | 0.13 | 34 | No |

| Arkansas | 0.12 | 35 | Yes |

| Maine | 0.11 | 36 | Yes |

| North Dakota | 0.10 | 37 | No |

| Oklahoma | 0.09 | 38 | Yes |

| Kentucky | 0.09 | 39 | Yes |

| Alaska | 0.09 | 40 | Yes |

| Alabama | 0.09 | 41 | Yes |

| Iowa | 0.08 | 42 | No |

| Indiana | 0.08 | 43 | No |

| Nebraska | 0.07 | 44 | No |

| Mississippi | 0.06 | 45 | Yes |

| Kansas | 0.06 | 46 | No |

| Idaho | 0.05 | 47 | No |

| West Virginia | 0.04 | 48 | Yes |

| Wyoming | Not disclosable | NA | Yes |

| Delaware | Not disclosable | NA | No |

The effect of tax preferences on the motion picture industry location quotient is unclear. States that allowed their incentives to expire, Arizona, Indiana, Iowa, and Kansas, experienced a declining concentration of motion picture industry employment before their incentives expired. Washington’s location quotient grew before the tax incentive was enacted in 2006. Exhibit 6 below shows Washington’s motion picture location quotients compared to states that have allowed their motion picture incentives to expire.

2. Provide Family Wage Jobs With Health and Retirement Benefits

It is unclear whether the preference is meeting the objective.

Due to changes in the reporting requirements and survey instrument consistent with the Legislative Auditor’s 2010 recommendations, JLARC staff were only able to review two years of production survey data.

Motion picture projects tend to be short in duration, averaging 52 days in Washington including preparation, production, and post-production time. The projects qualifying for funding assistance created 1,382 part-time production positions for Washington residents working on feature film, episodic series, or commercial projects and averaged 115,000 hours of annual employment for Washington residents, or the equivalent of 55 full-time employees.

Average wages for Washington residents hired to work on qualifying commercials and feature films are shown in Exhibit 7 below compared to average Washington private and public sector wages. Wages vary by type of film project and by type of job, and range from $80 an hour for cast to $10 an hour for extras. Washington private sector wages average $31 an hour and Washington public sector wages average $29 an hour. Crew members make up 80 percent of the total hours worked, followed by production assistants (PAs) at 12 percent, extras at 6 percent, and cast at 2 percent.

| Type of Project/Type of Job | Average Hourly Wage | % of Total Hours Worked (115,000 Hours Total) |

|---|---|---|

| Commercials | ||

| Cast | No employees reported in the survey | |

| Crew | $57 | 8% |

| PAs | $17 | 2% |

| Extras | $40 | 1% |

| Feature Films & Post Production | ||

| Cast | $80 | 2% |

| Crew | $26 | 72% |

| PAs | $13 | 10% |

| Extras | $10 | 5% |

| Weighted Average Across All Projects | $26 | |

| Private Sector Average Hourly Wage in WA |

$31 | |

| Public Sector Average Hourly Wage in WA |

$29 | |

Source: JLARC staff analysis of Department of Commerce and Employment Security Department data.

Projects are required to provide health and retirement benefits for positions covered by collective bargaining agreements which generally include skilled professionals such as cast and crew members. Extras tend to be unskilled positions and typically do not receive benefits. Exhibit 8 below shows that the percentage of projects providing health and retirement benefits to workers ranges from 100 percent for cast and crew to no benefits for extras.

| Type of Project | % Projects Providing Benefits to | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cast | Crew | PAs | Extras | |

| Commercials | N/A | 100% | 58% | 8% |

| Feature Films & Post Production | 100% | 100% | 29% | 0% |

Source: JLARC staff analysis Department of Commerce and Employment Security Department data.

Who are the entities whose state tax liabilities are directly affected by the tax preference?

The beneficiaries of the B&O tax credit for motion picture contributions include the Washington business contributors and the motion picture companies receiving funding assistance from the Motion Picture Competitiveness Program (MPCP).

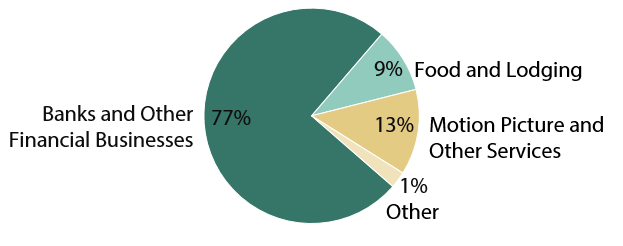

The Washington Business Contributors

Businesses may claim a B&O tax credit equal to the amount of contributions they make to the MPCP. Exhibit 9 below shows that banks and other financial businesses claimed the highest percent of tax credit at 77 percent over the life time of the program, followed by motion picture and other business services (13 percent), and food and lodging businesses (9 percent). These firms may claim the lesser of $1 million or the extent of the firm’s tax liability over the current tax year plus three years.

The Motion Picture Production Projects

Motion picture projects apply for assistance from the MPCP to cover a share of their Washington costs. Exhibit 10 below shows that feature films and their related post production work have received 82 percent of all MPCP funding over the life of the program. Commercials received the next largest share of funding at 15 percent followed by episodic series which received 3 percent of funding.

What are the past and future tax revenue and economic impacts of the tax preference to the taxpayer and to the government if it is continued?

Exhibit 11 below shows the actuals for Fiscal Years 2013 and 2014 differ from the annual cap of $3.5 million because the cap is administered on a calendar year cycle. The actual credit claimed in Fiscal Year 2014 was $5.2 million. The estimated beneficiary savings for the 2015-17 Biennium is $7 million.

| Fiscal Year | Motion Picture Tax Credit Beneficiary Savings |

|---|---|

| 2012 | $2,171,653 |

| 2013 | $1,661,719 |

| 2014 | $5,188,889 |

| 2015 | $3,500,000 |

| 2016 | $3,500,000 |

| 2017 | $3,500,000 |

| 2015-17 Biennium | $7,000,000 |

If the tax preference were to be terminated, what would be the negative effects on the taxpayers who currently benefit from the tax preference and the extent to which the resulting higher taxes would have an effect on employment and the economy?

For those preferences enacted for economic development purposes, what are the economic impacts of the tax preferences compared to the economic impact of government activities funded by the tax?

JLARC staff estimated four measures of economic impact as a result of the Motion Picture Competitiveness Program (MPCP). The analyses ask if the motion picture tax preference pays for itself in terms of:

- New jobs;

- New personal income;

- New economic activity; and

- New tax revenues.

Each estimate involved varying the assumption on how much film industry spending is caused by the tax preference. Economists often use this approach to model the “but for?” question: “but for” the preference, would the spending have taken place? Each estimate also included a reduction in economic impacts that may occur if the preference resulted in reduced government spending. (See technical appendix for detail on JLARC staff’s estimates.)

1. Is there a net increase in jobs resulting from the tax preference?

There is a range of possible answers.

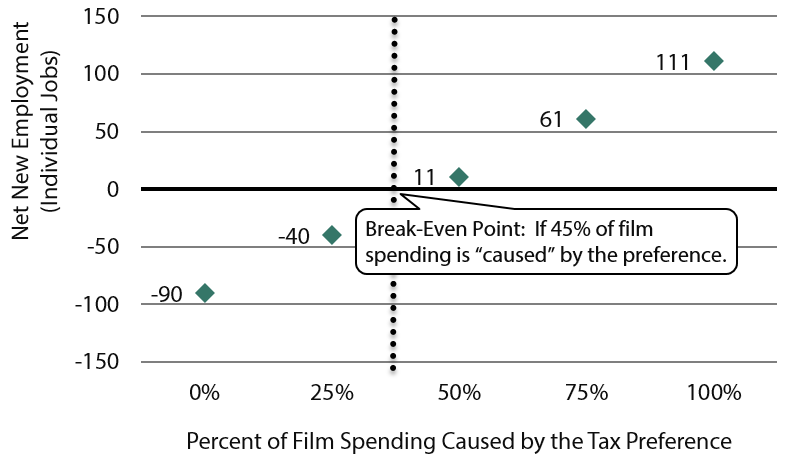

In the absence of knowing whether or not location decisions for individual film projects are “caused” by the tax preference, JLARC staff tested multiple assumptions about the level of activity taking place in Washington due to the preference. Exhibit 12 shows the estimated net results for new employment for different levels of assumptions regarding how much economic activity was caused by the preference.

For example, if 100 percent of reported film activity is due to the preference, JLARC staff estimated a net gain of 111 economy-wide jobs. If all of the film activity would have taken place despite the incentive, the estimated net loss is 90 jobs across the state economy. These job estimates reflect an assumption that the state forgoes public sector spending and employment in order to provide the incentive to qualifying film projects.

The break-even point, where job losses from foregone public sector spending are offset by job gains due to the preference, is when 45 percent of film spending by firms receiving assistance is caused by the tax preference.

2. Is there a net increase in overall personal income resulting from the tax preference?

There is a range of possible answers.

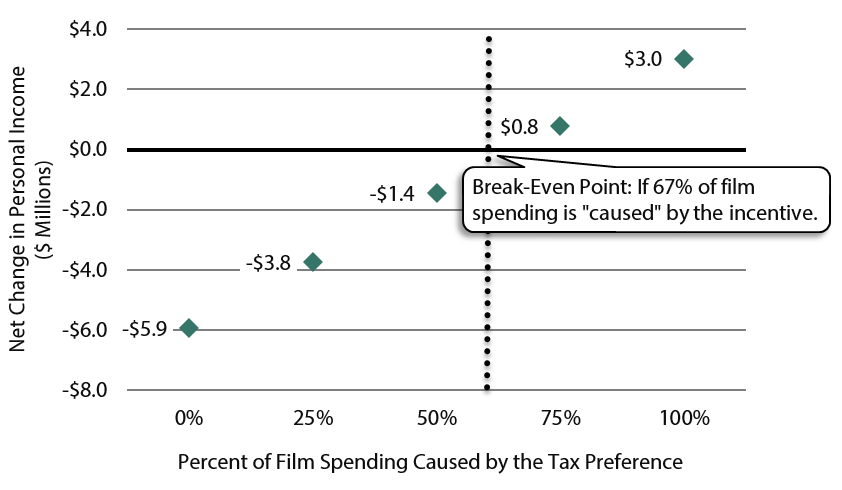

Exhibit 13 shows the estimated net results for aggregate statewide personal income for different levels of assumptions regarding how much economic activity was caused by the preference.

For example, if 100 percent of reported film activity is due to the preference, JLARC staff estimate a net increase of $3 million in personal income. If all of the film activity would have taken place despite the incentive, the estimated net loss is $5.9 million in personal income. These estimates reflect an assumption that the state forgoes public sector spending and employment in order to provide the incentive to qualifying film projects.

The break-even point, where personal income losses from foregone public sector spending are offset by personal income gains due to the preference, is when 67 percent of film spending by firms receiving assistance is caused by the tax preference.

Personal income is a measure used by economists to understand what individuals are earning from all sources, and these earnings eventually impact consumer spending. Personal income is included to augment the jobs estimates to provide a more complete picture of how motion picture spending impacts economic activity statewide. New jobs with higher wages will increase personal income more than new jobs with lower wages.

3. Is there a net increase in overall economic activity resulting from the tax preference?

There is a range of possible answers.

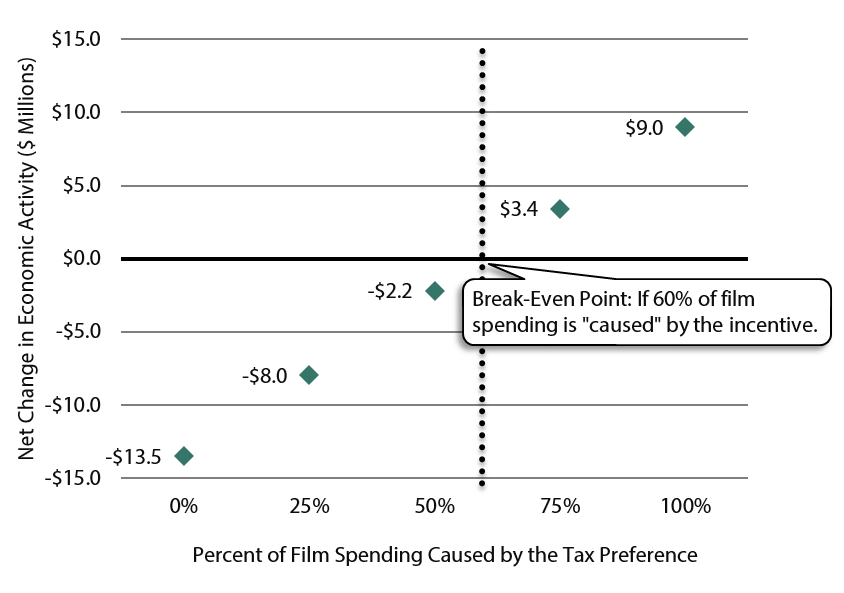

Exhibit 14 shows the estimated results for overall economic activity for different levels of preference-induced economic activity.

For example, if 100 percent of reported film activity is due to the preference, JLARC staff estimate a net gain of $9 million in overall economic activity in the state. If all of the film activity would have taken place despite the incentive, the estimated net loss is $13.5 million in economic activity. These estimates reflect an assumption that the state forgoes public sector spending in order to provide the incentive to qualifying film projects.

The break-even point, where reductions in economic activity losses from foregone public sector spending are offset by increased economic activity due to the preference, is when 60 percent of film spending by firms receiving assistance is caused by the tax preference.

The break-even point is different depending on the type of economic impact that is measured (jobs, personal income, or economic activity).

When the focus is jobs, the break-even point is 45 percent (Exhibit 12), for personal income it is 67 percent (Exhibit 13), and for overall economic activity it is 60 percent (Exhibit 14). In order to compensate for job losses in the public sector, at least 45 percent of the in-state employment and spending by film production companies needs to be “caused” by the incentive. However, this same level is not enough to regain losses in terms of personal income and economic activity. To accomplish this, the incentive would need to have caused between 60 and 67 percent of the film productions’ in-state spending.

4. Do the taxes generated by increased economic activity offset the reduction in taxes foregone due to the preference?

No, it does not, even if using the assumption that 100 percent of spending in Washington by film companies receiving assistance is caused by the tax preference.

Film companies generate economic activity in the state which, in turn, generates new tax revenues. However, any new tax revenues are more than offset by the state’s tax credit of $3.5 million.

JLARC staff estimated that the tax preference results in a net reduction of $3.3 million, after accounting for taxes from additional economic activity. This equates to collecting six cents of new taxes for every dollar of taxes foregone due to the preference. JLARC staff based this estimate on the “best case” scenario that 100 percent of the film company spending in Washington is “caused” by the rebate. See Exhibit 15 below.

| Tax Revenues Generated by Economic Activity | Estimated 4-Year Average |

|---|---|

| New Sales Taxes | $122,000 |

| New B&O Taxes | $48,000 |

| New Other Taxes | $33,000 |

| Total new state taxes | $203,000 |

| Reduction in state taxes due to credit | ($3,500,000) |

| Net change in taxes | ($3,297,000) |

| New Taxes for Every One Dollar of Tax Credit | $0.06 |

Results for Changes in Tax Revenues Are Comparable to Film Incentive Studies Conducted by Other States

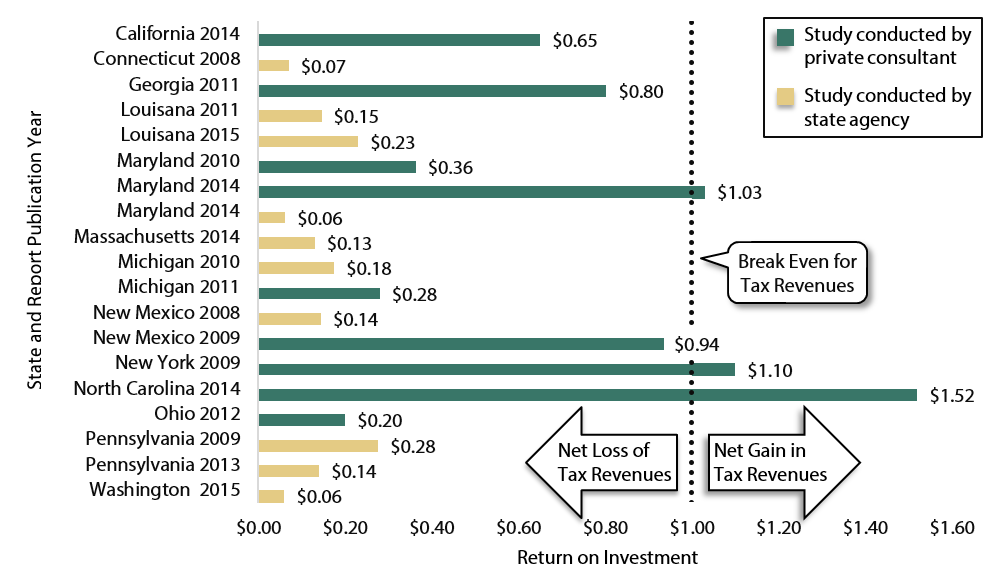

JLARC staff reviewed studies estimating economic impacts on changes in tax revenues for other states’ film tax incentives conducted between 2008 and 2015.

The studies were conducted by state government agencies or consultants on behalf of state government, or by private entities. The studies include estimated tax revenues generated by economic activity resulting from their state’s film tax incentive.

State government studies estimated new tax revenues ranging from $.06 to $.28 for every dollar of film tax incentive. New tax revenue estimates by private consultants range from $.20 to $1.52 for every dollar of tax incentive. Exhibit 16 below compares these studies.

To estimate economic impacts of the motion picture competitiveness program (MPCP) JLARC staff used a model developed for Washington by Regional Economic Models, Inc. (REMI), which is the same model used to analyze the aerospace industry tax preferences in 2014. The REMI model is used by 30 state governments and a number of private sector consulting firms and research universities. The model incorporates aspects of four major modeling approaches: input-output, general equilibrium, econometric, and economic geography. The model is based on a complex set of mathematical equations designed to capture the interrelationships between sectors of Washington’s economy including private industry, consumers, and government.

The REMI software allows users to simulate policy initiatives within the state and includes the estimation of direct, indirect, and induced effects of a policy change as these effects spread through the state’s economy.

- Direct effects are industry specific and capture how businesses or an industry responds to a particular policy change (e.g., employment and spending decisions by motion picture production companies working in Washington and benefitting from the tax preference);

- Indirect effects capture employment and spending decision by businesses providing goods and services for the film industry (e.g., hotels); and

- Induced effects capture the in-state spending practices of individuals employed in the film industry and sectors that support it. Consumer spending patterns are a response to changes in direct and indirect spending on employee compensation.

The REMI model includes features that make it particularly useful for this analysis:

- In consultation with staff from OFM, REMI staff customized the model to reflect the economy of Washington;

- The REMI model contains 160 industry sectors and forecasts effects multiple years into the future; and

- The REMI model includes state and local government as a sector within the model. This ability to estimate the impact of government spending on the economy is a special feature of REMI.

Key Assumptions

All of the analyses described above use the same assumptions for film industry jobs and spending and for reductions in state government spending. Analysis of impacts on jobs, personal income, and overall economic activity consider a range of assumptions about the amount of motion picture activity that would take place in the state with or without the tax preference.

Film Industry Jobs and Spending

Direct inputs into the REMI model include the number of Washington residents hired and expenditures on goods and services made in Washington by the film companies that received assistance from the MPCP. Goods and services include categories such as food and accommodation, air and ground transportation, and professional services.

These amounts are based on detailed data verified by Washington Filmworks from surveys submitted by the beneficiary film companies to the Department of Commerce after production is complete.

Beneficiaries of the rebate reported how many Washington residents they hired, and the duration they worked. The average number of hours worked by Washington residents in 2013 and 2014 averaged 115,000. JLARC staff converted total jobs hours to full-time equivalent (FTE) workers for the purpose of modeling the estimated economic impacts of MPCP-related film spending. This employment is equivalent to 55 FTE positions. Beneficiaries also reported that they spent $4.6 million on goods and services a year, averaged over 2013 and 2014.

Film companies also reported that 51 percent to 59 percent of their qualified spending in Washington is exempt from the sales tax. Film companies located out of state generally are not liable for B&O tax in Washington.

State Government Spending

The analyses assume that the Legislature would respond to the revenue loss from the preference by reducing spending by the amount of the tax credit, $3.5 million per year. The assumed reductions in spending are in the same proportions as current government spending.

Alternatively, the Legislature could respond by raising taxes or reducing funding in specific areas of the budget. However, in the absence of such evidence, JLARC staff did not model these alternate options.

Motion Picture Activity With or Without the Credit

One key factor in estimating net impacts is how much motion picture activity takes place in the state because of the tax preference and how much would take place regardless of the preference. Because the true percentage is unknown, the analyses consider a range of possibilities.

At one end of the spectrum is the assumption that 100 percent of film spending is “caused” by the availability of the preference, that is, that none of the motion picture activity would have occurred without the preference. At the other end of the spectrum is the assumption that zero percent of film spending is “caused” by the preference, that is, that all of the motion picture activity in Washington would have happened anyway.

The true percentage may be somewhere in between these two extremes. For example, California film companies with cast and crew members from California might have been induced to film in Washington by the tax incentive. In contrast, Washington-based film companies might have still received requests to make commercials in state for Washington products without the tax incentive. However, all of these production companies could apply for the tax credit.

JLARC staff modeled different scenarios to estimate whether the state’s investment in the film industry paid for itself in new economic activity. As shown in Exhibit 17 below, the state provides the same $3.5 million tax credit under each scenario, but the percentage of film production employment and spending on goods and services “caused” by the rebate is reduced from 100 percent to 75 percent, 50 percent, 25 percent, and zero percent.

| Assumptions: Percent of Film Spending "Caused" by Tax Credit | Number of Direct Film FTE Positions (Individual Jobs) | Increased Direct Film Company Spending on Goods and Services ($Millions) | Reduced Direct State Spending ($Millions) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 100% | 55 | $4.6 | $3.5 |

| 75% | 41 | $3.4 | $3.5 |

| 50% | 28 | $2.3 | $3.5 |

| 25% | 14 | $1.1 | $3.5 |

| 0% | 0 | $0.0 | $3.5 |

The state receives a diminishing return on its tax investment if the percentage declines because the tax credit is assumed to cause a smaller amount of film production spending, and the state is providing reimbursements for a larger percentage of film production spending that may have taken place anyway without the inducement.

Output Multipliers

The estimated economic impacts shown for the various scenarios in the MPCP analysis depend in part on the effects of multipliers in the REMI model. The calculation of multipliers is an accepted method for estimating different aspects of economic activity. These values provide estimates of how economic activity may increase or decrease given different assumptions. Multipliers are calculated as a ratio of total direct (initial), indirect (spin-off or suppliers), and induced (consumer spending) effects to the direct effect.

There are multipliers throughout the REMI model, reflecting actual spending and consumption patterns for multiple sectors in the economy. For example, the REMI jobs multiplier resulting from spending by the film projects funded by the incentive is 3.7. This indicates that for every one job created in the film industry, the statewide economy realizes an additional 2.7 jobs.

Do other states have a similar tax preference and what potential public policy benefits might be gained by incorporating a corresponding provision in Washington?

Exhibit 18 below shows that 37 states, including Washington, provide incentives to the motion picture industry in the form of tax credits, grants, or rebates. Like Washington, 32 states require a minimum investment by the film company, and 26 have an annual cap on the amount of state funding. The amount of funding ranges from 15 percent of qualified investment to 58 percent.

| State | Expires | Type of Preference |

Annual Cap $Millions |

Project Cap $Millions |

Maximum Percent Funding |

Minimum Investment for Film |

Location Quotient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | No | Rebate | $20 | $7 | 35% | $500,000 | 0.09 |

| Alaska | 2018 | Transferable Credit | $200 thru 2018 | None | 58% | $75,000 | 0.09 |

| Arizona | Expired 2010 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.13 |

| Arkansas | 2019 | Rebate | None | None | 30% | $200,000 | 0.12 |

| California | 2017 | Credit | $330 | None | 25% | $1,000,000 | 4.45 |

| Colorado | No | Rebate | $5 | None | 20% | $1,000,000 | 0.34 |

| Connecticut | No | Transferable Credit | None | None | 30% | $100,000 | 1.07 |

| Delaware | No Preference | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Florida | 2016 | Transferable Credit | $296 | $8 | 30% | $100,000 | 0.34 |

| Georgia | No | Transferable Credit | None | None | 30% | $500,000 | 0.63 |

| Hawaii | 2018 | Refundable Credit | None | $15 | 25% | $200,000 | 1.22 |

| Idaho | Not Funded | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.05 |

| Illinois | 2021 | Transferable Credit | None | None | 45% | $100,000 | 0.20 |

| Indiana | Expired 2011 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.08 |

| Iowa | Suspended 2009 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.08 |

| Kansas | Expired 2012 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.06 |

| Kentucky | No | Refundable Credit | None | None | 20% | $500,000 | 0.09 |

| Louisiana | No | Transferable Credit | None | None | 35% | $300,000 | 1.88 |

| Maine | No | Rebate/Credit | None | None | 17% | $75,000 | 0.11 |

| Maryland | 2016 | Refundable Credit | $7.5 | None | 27% | $500,000 | 0.33 |

| Massachusetts | 2022 | Rebate/Credit | None | None | 25% | $50,000 | 0.51 |

| Michigan | 2017 | Rebate | $50 | None | 35% | $100,000 | 0.24 |

| Minnesota | No | Rebate | $10 | $5 | 25% | $100,000 | 0.19 |

| Mississippi | 2016 | Rebate | $20 | $10 | 35% | $50,000 | 0.06 |

| Missouri | Expired 2013 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.13 |

| Montana | 2016 | Refundable Credit | None | None | 34% | None | 0.33 |

| Nebraska | No Preference | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.07 |

| Nevada | 2017 | Transferable Credit | $20 | $6 | 19% | $500,000 | 0.61 |

| New Hampshire | No Preference | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.17 |

| New Jersey | 2015 | Transferable Credit | $10 | None | 20% | None | 0.46 |

| New Mexico | No | Transferable Credit | $50 | None | 30% | None | 1.52 |

| New York | 2019 | Transferable Credit | $420 | None | 35% | None | 3.35 |

| North Carolina | No | Transferable Credit | None | $20 | 25% | $250,000 | 0.14 |

| North Dakota | No Preference | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.10 |

| Ohio | No | Transferable Credit | $40 | $5 | 35% | $300,000 | 0.14 |

| Oklahoma | 2024 | Rebate | $5 | None | 37% | $25,000 | 0.09 |

| Oregon | 2017 | Rebate | $10 | None | 20% | $1,000,000 | 0.92 |

| Pennsylvania | No | Transferable Credit | $60 | $12 | 30% | None | 0.33 |

| Rhode Island | 2019 | Transferable Credit | $15 | $5 | 25% | $100,000 | 0.24 |

| South Carolina | No | Rebate | $10 | None | 30% | $1,000,000 | 0.16 |

| South Dakota | Expired 2011 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.18 |

| Tennessee | No | Rebate | $2 | None | 25% | $200,000 | 0.38 |

| Texas | No | Grant | $95 | None | 22.50% | $250,000 | 0.26 |

| Utah | No | Rebate/Credit | $6.79 | None | 25% | $200,000 | 0.70 |

| Vermont | No Preference | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.17 |

| Virginia | 2018 | Transferable Credit | $6.5 | None | 40% | $250,000 | 0.26 |

| Washington | 2017 | Rebate | $3.5 | None | 35% | $500,000 | 0.35 |

| West Virginia | No | Transferable Credit | $5 | None | 31% | $25,000 | 0.04 |

| Wisconsin | Terminated 2013 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.14 |

| Wyoming | 2016 | Rebate | $0.9 | None | 15% | $200,000 | ND |

Generally, states provide assistance for feature films and episodic series. Smaller productions such as commercials, interactive video, music video, news, and sporting events are less often funded. Of these smaller productions, Washington provides funding to commercials, but not video games, sporting events, and news. Funding through Washington’s Innovation Lab may be provided to smaller productions produced by Washington filmmakers using new forms of production and emerging technologies.

RCW 82.04.4489

Credit - Motion picture competitiveness program.

(1) Subject to the limitations in this section, a credit is allowed against the tax imposed under this chapter for contributions made by a person to a Washington motion picture competitiveness program.

(2) The person must make the contribution before claiming a credit authorized under this section. Credits earned under this section may be claimed against taxes due for the calendar year in which the contribution is made. The amount of credit claimed for a reporting period may not exceed the tax otherwise due under this chapter for that reporting period. No person may claim more than one million dollars of credit in any calendar year, including credit carried over from a previous calendar year. No refunds may be granted for any unused credits.

(3) The maximum credit that may be earned for each calendar year under this section for a person is limited to the lesser of one million dollars or an amount equal to one hundred percent of the contributions made by the person to a program during the calendar year.

(4) Except as provided under subsection (5) of this section, a tax credit claimed under this section may not be carried over to another year.

(5) Any amount of tax credit otherwise allowable under this section not claimed by the person in any calendar year may be carried over and claimed against the person's tax liability for the next succeeding calendar year. Any credit remaining unused in the next succeeding calendar year may be carried forward and claimed against the person's tax liability for the second succeeding calendar year; and any credit not used in that second succeeding calendar year may be carried over and claimed against the person's tax liability for the third succeeding calendar year, but may not be carried over for any calendar year thereafter.

(6) Credits are available on a first in-time basis. The department must disallow any credits, or portion thereof, that would cause the total amount of credits claimed under this section during any calendar year to exceed three million five hundred thousand dollars. If this limitation is reached, the department must notify all Washington motion picture competitiveness programs that the annual statewide limit has been met. In addition, the department must provide written notice to any person who has claimed tax credits in excess of the limitation in this subsection. The notice must indicate the amount of tax due and provide that the tax be paid within thirty days from the date of the notice. The department may not assess penalties and interest as provided in chapter 82.32 RCW on the amount due in the initial notice if the amount due is paid by the due date specified in the notice, or any extension thereof.

(7) To claim a credit under this section, a person must electronically file with the department all returns, forms, and any other information required by the department, in an electronic format as provided or approved by the department. Any return, form, or information required to be filed in an electronic format under this section is not filed until received by the department in an electronic format. As used in this subsection, "returns" has the same meaning as "return" in RCW 82.32.050.

(8) No application is necessary for the tax credit. The person must keep records necessary for the department to verify eligibility under this section.

(9) A Washington motion picture competitiveness program must provide to the department, upon request, such information needed to verify eligibility for credit under this section, including information regarding contributions received by the program.

(10) The department may not allow any credit under this section before July 1, 2006.

(11) For the purposes of this section, "Washington motion picture competitiveness program" or "program" means an organization established pursuant to chapter 43.365 RCW.

(12) No credit may be earned for contributions made on or after July 1, 2017.

[2012 c 189 § 4; 2008 c 85 § 3; 2006 c 247 § 5.]

RCW 43.365.020

Program criteria - Permissible expenditures - Maximum funding assistance - Funding assistance approval - Rules.

(1) The department must adopt criteria for the approved motion picture competitiveness program with the sole purpose of revitalizing the state's economic, cultural, and educational standing in the national and international market of motion picture production. Rules adopted by the department shall allow the program, within the established criteria, to provide funding assistance only when it captures economic opportunities for Washington's communities and businesses and shall only be provided under a contractual arrangement with a private entity. In establishing the criteria, the department shall consider:

(a) The additional income and tax revenue to be retained in the state for general purposes;

(b) The creation and retention of family wage jobs which provide health insurance and payments into a retirement plan;

(c) The impact of motion picture projects to maximize in-state labor and the use of in-state film production and film postproduction companies;

(d) The impact upon the local economies and the state economy as a whole, including multiplier effects;

(e) The intangible impact on the state and local communities that comes with motion picture projects;

(f) The regional, national, and international competitiveness of the motion picture filming industry;

(g) The revitalization of the state as a premier venue for motion picture production and national television commercial campaigns;

(h) Partnerships with the private sector to bolster film production in the state and serve as an educational and cultural purpose for its citizens;

(i) The vitality of the state's motion picture industry as a necessary and critical factor in promoting the state as a premier tourist and cultural destination;

(j) Giving preference to additional seasons of television series that have previously qualified;

(k) Other factors the department may deem appropriate for the implementation of this chapter.

(2) The board of directors created under RCW 43.365.030 shall create and administer an account for carrying out the purposes of subsection (3) of this section.

(3) Money received by the approved motion picture competitiveness program shall be used only for:

(a) Health insurance and payments into a retirement plan, and other costs associated with film production; and

(b) Staff and related expenses to maintain the program's proper administration and operation.

(4) Except as provided otherwise in subsection (7) of this section, maximum funding assistance from the approved motion picture competitiveness program is limited to an amount up to thirty percent of the total actual investment in the state of at least:

(a) Five hundred thousand dollars for a single motion picture produced in Washington state; or

(b) One hundred fifty thousand dollars for a television commercial associated with a national or regional advertisement campaign produced in Washington state.

(5) Except as provided otherwise in subsection (7) of this section, maximum funding assistance from the approved motion picture competitiveness program is limited to an amount up to thirty-five percent of the total actual investment of at least three hundred thousand dollars per episode produced in Washington state. A minimum of six episodes of a series must be produced to qualify under this subsection. A maximum of up to thirty percent of the total actual investment from the approved motion picture competitiveness program may be awarded to an episodic series of less than six episodes.

(6) With respect to costs associated with nonstate labor for motion pictures and episodic services, funding assistance from the approved motion picture competitiveness program is limited to an amount up to fifteen percent of the total actual investment used for costs associated with nonstate labor. To qualify under this subsection, the production must have a labor force of at least eighty-five percent of Washington residents. The board may establish additional criteria to maximize the use of in-state labor.

(7)(a) The approved motion picture competitiveness program may allocate an annual aggregate of no more than ten percent of the qualifying contributions by the program under RCW 82.04.4489 to provide funding support for filmmakers who are Washington residents, new forms of production, and emerging technologies.

(i) Up to thirty percent of the actual investment for a motion picture with an actual investment lower than that of motion pictures under subsection (4)(a) of this section; or

(ii) Up to thirty percent of the actual investment of an interactive motion picture intended for multiplatform exhibition and distribution.

(b) Subsections (4) and (5) of this section do not apply to this subsection.

(8) Funding assistance approval must be determined by the approved motion picture competitiveness program within a maximum of thirty calendar days from when the application is received, if the application is submitted after August 15, 2006.

[2012 c 189 § 2; 2009 c 100 § 1; 2008 c 85 § 1; 2006 c 247 § 3.]

- Legislative Auditor Recommendation

- Commissioners’ Recommendation

- Letter from Commission Chair

- Agency Response

Legislative Auditor Recommendation: Review and Clarify

The Legislature should review and clarify the policy objective for the tax credit for contributions to the Motion Picture Competitiveness Program, providing additional detail on the target for Washington’s industry relative to other states, as well as desired employment outcomes for jobs, average hourly wages, and health and benefits coverage.

While there is information available on industry share and employment, it is unclear what level of outcomes the Legislature would like to achieve for these measures:

- Washington’s concentration of motion picture employment is below the national average, but ranks in the top third of the nation.

- Beneficiaries provide an average of 115,000 hours of employment a year to Washington residents, or 55 full-time equivalent jobs.

- The average hourly wages for 90 percent of the hours worked on qualifying projects are below the Washington average hourly wage.

- Beneficiaries are required to provide health and retirement benefits for positions covered by collective bargaining agreements which generally include cast and crew, but may not include production assistants and extras.

Additional detail should provide guidance on:

- The Legislature’s desired increase in the number and quality of jobs; and

- Criteria for determining if Washington has achieved the objective of regaining and revitalizing the competitive position in the motion picture industry.

The Legislative Auditor’s guidance document for drafting performance statements provides a framework for identifying policy objectives and linking these to performance metrics.

Legislation Required: Yes.

Fiscal Impact: Depends on legislative action.

The Commission endorses the Legislative Auditor’s recommendation without comment.