JLARC Proposed Final Report: 2015 Tax Preference Performance Reviews

Interest on Real Estate Loans | B&O Tax

- Summary of this Review

- Details on this Preference

- Recommendations and Agency Response

- How We Do Reviews

- More about this Review

| The Preference Provides | Tax Type | Est. Beneficiary Savings in 2015-17 Biennium |

|---|---|---|

| Banks and other financial institutions may receive a business and occupation (B&O) tax deduction for the interest they receive on loans for residential property. | B&O RCWs 82.04.4292; 82.04.29005 |

$49.8 million |

| Public Policy Objective |

|---|

The Legislature did not state a public policy objective. JLARC staff infer the objectives were to:

|

| Recommendations |

|---|

| Legislative Auditor Recommendation: Review and Clarify Because:

Commissioner Recommendation: The Commission does not endorse the Legislative Auditor’s recommendation and recommends that the Legislature should maintain the 2012 legislation defining which lenders qualify for the preference. Washington State financial institutions that portfolio mortgage loans compete with their counterparts in other states who are subject to different tax regimes. The industry’s testimony made the reasonable argument that the current tax preference helps mitigate the competitive disadvantage created by recent federal regulatory changes. In this new environment, smaller financial institutions are struggling to absorb the increase in regulatory costs associated with lending. Although offsetting regulatory costs was not the preference’s original stated intent, the preference appears to enable smaller financial firms to compete with (1) large nationally-based financial firms whose size enables them to absorb these additional costs and (2) credit unions, which have special tax status. Indicative of increased cost pressures facing smaller community banks, the number of community banks nationally has fallen from about 7,000 in 2008 to 5,400 recently (a 23% decline). Over this same time period, the number of commercial banks headquartered in Washington State has declined from 81 to 45 (a 44% decline). While there are many factors driving shrinkage in the number of community banks, limiting the current preference in same fashion could aggravate that trend. Furthermore, the inferred public policy objectives do not capture the legislative debate and compromise that surrounded the compromise reached to determine the class and type of banks that would continue to qualify for the exemption. Specifically, the current testimony and debate at the time of the 2012 legislation indicated the restructuring of the exemption was to provide a benefit to a certain population of smaller, local lending institutions without violating commerce clause restrictions imposed by the courts. The community bank definitions considered by JLARC staff were not adopted during legislative debate of these provisions because they would not have encompassed the full population of banks the Legislature determined should be covered. |

- What is the Preference?

- Legal History

- Other Relevant Background

- Public Policy Objectives

- Are Objectives Being Met?

- Beneficiaries

- Revenue and Economic Impacts

- Other States with Similar Preference?

- Applicable Statutes

Banks and other financial businesses may receive a business and occupation (B&O) tax deduction for the interest they receive on loans for residential property. Three factors determine whether the business may receive the deduction:

- It must be a qualifying loan

- From a qualifying lender

- For qualifying property

Qualifying loans

The loan must be primarily secured by a first lien mortgage or a trust deed. The borrower may use the loan to purchase property such as a home but may also use it for other purposes such as home improvement or refinancing.

Qualifying lenders

The bank or other financial business making the loan must be located in 10 or fewer states. Being located in a state means the business or an affiliate must:

- Maintain a branch, office, or one or more employees or representatives in 10 or fewer states; and

- This state presence must allow borrowers to contact the branch, office, employee, or representative concerning mortgage loans.

Commercial banks, savings and loans associations, and savings banks (referred to collectively as “banks” in this review) qualify as financial businesses eligible for the deduction. Credit unions have a full exemption from B&O tax under a different preference that JLARC staff reviewed in 2011.

Mortgage companies also qualify if they are classified as “a lending mortgage broker” that uses its own funding source to advance funds to the borrower and bears the risk of interest rate fluctuations. A mortgage broker that acts as an agent for the lender does not qualify.

Qualifying property

The loan must be for “non-transient residential property” in Washington. This includes property such as homes, apartments, and construction of residential property. It excludes property such as hotels and motels. Exhibit 1 below provides more examples of what property qualifies and what does not.

| Qualifies | Does Not Qualify |

|---|---|

| Single family residences | Permanent care nursing homes or convalescent homes |

| Apartments | Hotels or motels |

| Construction of residential property, including trailer park sites | Transient apartments where occupants stay less than 30 days |

| Farmland where the value of the residential structure exceeds the land value | Churches |

The Legislature attempted unsuccessfully to tax the income of national banks in 1929, 1933, and 1935. In all three instances, the courts found the tax to be in violation of the U.S. Constitution. The Legislature consequently decided it would not tax state banks. As a result, Washington exempted from B&O taxation all bank income of any kind.

1969

Congress reversed long-standing prohibitions and allowed states to tax national banks, but not federally chartered credit unions.

1970

The Legislature repealed the B&O exemption for national and state banks and certain other financial institutions. In the same bill, the Legislature provided specific deductions to maintain the tax status of certain financial income, such as income covered by this tax preference.

Following enactment of the 1970 statute, the Department of Revenue (DOR) and stakeholders engaged in 40 years of administrative appeals and litigation on the tax preference. For the most part, subsequent rulings expanded the scope of the deduction. For a more detailed discussion, see the review of “Interest on Real Estate Loans,” conducted by JLARC staff in 2011.

2010

The Legislature codified many of these previous rulings and clarified which points, loan servicing fees, and other fees may be included when calculating the deduction.

2011

JLARC staff reviewed the B&O tax deduction for first lien mortgage interest and inferred that the 1970 public policy objective was to stimulate the residential housing market by making residential loans available to home buyers at lower cost. The Legislative Auditor recommended the Legislature review and clarify this objective because it may no longer apply given changes in the lending industry. An example of a change in the lending industry is the growth in the secondary market for “securitized” mortgages (see Other Relevant Background tab for an explanation of “securitized” mortgages).

2012

In a larger bill to raise tax revenue, the Legislature indicated it wanted to limit the pool of qualifying lenders to “community banks.” The issue remained how to identify a “community bank” in a manner that did not violate the Commerce Clause of the U.S. Constitution. The Legislature chose to narrow the deduction to apply only to lenders located in 10 or fewer states. The Department of Revenue advised the Legislature that limiting the deduction in this manner would likely be in conformance with the Commerce Clause. The change was effective July 1, 2012.

The Legislature also included a requirement that JLARC conduct a second review of this deduction in 2015.

2014

The Washington Supreme Court confirmed in Cashmere Valley Bank v. Department of Revenue that interest from investments on “securitized” mortgages sold on the secondary market are not primarily secured by real estate and are not entitled to the deduction.

Portfolio Versus “Securitized” Mortgages

When a home buyer borrows money from a lender to purchase a home, the borrower gives the lender a mortgage on the home as security for the loan. The lender then decides what to do with that mortgage.

- The lender may retain the mortgage in its portfolio;

- The lender may sell the mortgage to a buyer who receives the right to principal and interest payments on the loan and the right to foreclose on the loan if the borrower fails to make payments; or

- The holder of the mortgage (the originating lender or the buyer) may also choose to “securitize” a number of mortgages by pooling and packaging them into securities that are sold to investors on the secondary market.

Up until the mid-1980s, banks generally operated within local regions, soliciting deposits and making loans in their communities. Banks held mortgages in their own portfolios until the loans were paid off. The banking industry changed in the mid-1980s with the changes in regulatory laws allowing interstate branch banking and with the rise in the secondary mortgage market. In the current environment, most lenders sell their mortgages within a year of origination, but others may retain mortgages for various reasons. One reason is that the loan might fail to qualify under federal guidelines to be resold on the secondary market. Borrowers seeking loans that don’t qualify to be resold on the secondary market must find lenders willing to retain the mortgage in their portfolios. Some Washington banks retain 100 percent of their mortgages.

The Extent of the Preference the Lender Receives Depends on the Lender’s Choice to Retain or Sell the Mortgage

A lender’s choice whether to retain or sell a mortgage determines how that lender will benefit from the preference:

- Lenders that retain mortgages in their own portfolio may deduct the entire interest payment over the life of the loan.

- Other financial businesses that purchase mortgages may deduct the entire interest payment as long as the mortgage is not securitized.

- Lenders that sell mortgages in the secondary market receive the deduction on only a portion of the interest payment. They may deduct points and origination fees that are recognized over the life of the loan and servicing fees that are based on a percentage of the loan interest.

The amount of the exemption that a lender receives may influence the extent to which a lender passes on those savings to a home buyer in the form of a lower-cost loan. For example, a lender that is able to deduct the entire interest payment over the life of the loan may be in a better position to offer a home buyer a lower-cost loan than a lender that can deduct only a fraction of the interest payment.

What are the public policy objectives that provide a justification for the tax preference? Is there any documentation on the purpose or intent of the tax preference?

The Legislature did not state the specific public policy objective of this tax preference when it created the deduction in 1970. JLARC staff infer that the original objective was to stimulate Washington’s residential housing market by making loans available to home buyers at lower cost.

In 2012, the Legislature narrowed the deduction to apply to certain types of lenders (those located in 10 or fewer states) and stated its objective “to limit the tax preference to ‘community banks.’” In testimony supporting the 2012 legislation, the prime sponsor stated that community banks provided benefits to the local community that large banks do not. The prime sponsor described a “community bank” as a Washington-based bank:

“[There is] a bank in my district that never sold second mortgages [sold mortgages on the secondary market] and never laid off people even during the depression. Yet, their [FDIC] taxes have increased because of the need to pay off bad players. I am not sure why we should not exempt or carve out good players in our state that are home-grown Washington state business.”

Bank representatives testified on a 2011 bill to modify the tax preference that limiting or terminating the deduction would have an impact on portfolio lenders. They stated that portfolio lenders might need to increase interest rates or decrease residential loans in the future. They indicated that terms of loans already in place could not be restructured to adjust for the loss of the deduction. This testimony implies that the portfolio lenders were incorporating the exemption in the structuring of their loans.

In the 2011 review, the Legislative Auditor recommended that the Legislature review and clarify the first mortgage interest deduction given changes in the lending industry. In the 2012 bill amending the preference, the Legislature identified the type of lenders it intended to benefit. By limiting the preference to community banks, the Legislature may have been trying to achieve the original inferred public policy objective of stimulating Washington’s housing market by targeting lenders that could pass on the benefits to home buyers through lower cost loans. However, when the Legislature modified the statute to narrow the beneficiaries in 2012, it did not explicitly clarify the overall policy purpose for the underlying preference.

What evidence exists to show that the tax preference has contributed to the achievement of any of these public policy objectives?

It is unclear whether the preference is meeting the inferred objective.

The Legislature may have tried to limit the deduction to community banks because it anticipated that community banks are more likely to retain their mortgages and use principal and interest payments to make new loans in the local community. Lenders that retain mortgages benefit from the preference over the life of the loan and could choose to pass these savings on to home buyers. The availability of lower-cost loans might then stimulate Washington’s residential housing market.

JLARC staff analyzed evidence based on the assumption the tax preference would have a greater likelihood of impacting Washington’s housing market if:

- Mortgages are retained in the lender’s portfolio rather than sold;

- Loans are used for purchasing homes instead of other purposes such as refinancing; and

- Changes in Washington’s housing market are driven by local factors and not national trends.

Are Mortgages Retained or Sold?

More than two-thirds of mortgage amounts are sold. JLARC staff analyzed detailed data on mortgages originated in Washington. In 2013, qualifying lenders (those located in 10 or fewer states) retained an average of 29 percent of their first lien residential mortgage amounts within the year after loan origination. Exhibit 2 below shows that the percentage of mortgage amounts sold varied by the type of lender – bank or mortgage company. Data is for lenders that operate in 10 or fewer states.

| Type of Loan | Banks Loans |

Mortgage Company Loans |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| All WA Loans | $14.5 billion | $2.3 billion | $16.8 billion |

| WA Loans Retained in Originating Lender’s Portfolio |

$4.8 billion | $121.0 million | $4.9 billion |

| Percent Retained by Qualifying Lenders |

33% | 5% | 29% |

Are Loans Used for Purchasing Homes?

For the period 2007 to 2013, the percentage of qualifying loan amounts used for home purchases ranged between 26 and 47 percent. Qualifying loans can be used for other purposes such as home improvement or refinancing. Loans borrowed for these other purposes ranged from 54 percent to 74 percent of Washington loans originated by qualifying lenders over the same time period. It is unclear whether refinancing loans or home improvement loans contribute to the inferred public policy objective of stimulating the residential housing market.

Are Trends in Washington’s Housing Market Driven by Local Factors?

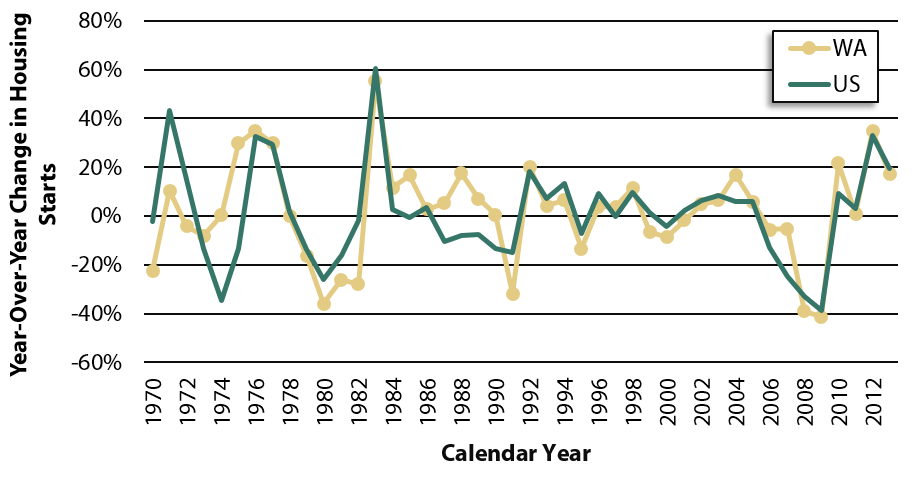

Washington housing starts follow national trends, making it less likely that the state’s tax policy can have an influence on the sale of residential mortgages in Washington. Exhibit 3 below shows that over the years 1970 through 2013, Washington housing starts follow the same pattern of peaks and troughs as national housing starts.

To what extent will continuation of the tax preference contribute to these public policy objectives?

To the extent a lender retains its mortgages and to the extent this lender passes on the cost savings from the tax preference to the home buyer, the tax preference lowers the cost of Washington loans. However, the effect of these cost savings on loan availability and on stimulating Washington’s overall housing market is less likely given that housing markets appear to follow national trends and do not appear to be driven by local factors.

If the public policy objectives are not being fulfilled, what is the feasibility of modifying the tax preference for adjustment of the tax benefits?

In the testimony supporting the 2012 legislation, the prime sponsor referenced home-grown Washington state businesses and banks that never sold mortgages on the secondary market. DOR counseled the Legislature that limiting the deduction to banks headquartered in Washington would violate the Commerce Clause of the U.S. Constitution, and the Legislature chose to limit the deduction to financial businesses operating in 10 or fewer states.

With this review, the Legislature now has information on the institutions that made loans that qualify for the preference following the 2012 law change and the amount of loans these institutions retained. If this is not the beneficiary pool the Legislature anticipated when it narrowed the preference, there are other ways to focus the preference that may not violate the Commerce Clause. Options include adopting either of two federal definitions of “community bank,” or the Legislature could focus on loans that are not sold on the secondary market, but that are instead retained in the lender’s portfolio. See the “Unintended Benefits” section under the Beneficiaries tab for more detail.

Who are the entities whose state tax liabilities are directly affected by the tax preference?

Beneficiaries of the tax preference are commercial banks, savings and loan associations, savings banks, and certain mortgage companies.

As shown in Exhibit 4 below, from publicly available data JLARC staff estimate that in 2013, a total of 204 banks and 48 mortgage companies made loans that met the criteria to qualify for the preference.

| Type of Mortgage Lender | Number of Institutions |

|---|---|

| Banks | 204 |

| Mortgage Companies | 48 |

| Total | 252 |

To what extent is the tax preference providing unintended benefits to entities other than those the Legislature intended?

In 2013, based on publicly available data 252 lenders made qualifying loans and met the current criterion for “community bank” (operating in 10 or fewer states).

If the Legislature wants to review how to focus the preference on community banks, below are three other options that may avoid the Commerce Clause concerns raised in 2012:

- The Federal Reserve Board (FRB), with supervisory responsibility over a number of commercial banks, thrifts, and bank holding companies, defines a “community bank” for regulatory purposes as a banking organization with assets of $10 billion or less.

- The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) defines a “community bank” for research purposes using a number of factors associated with the services they provide. According to FDIC, “community banks tend to be relationship lenders, characterized by local ownership, local control, and local decision making.” Among the factors that FDIC uses to define a community bank are asset size, loan to asset ratio, core deposits to asset ratio, number of total offices, and number of states with offices.

- The Legislature could focus its definition of “community bank” on portfolio lenders, that is, lenders that retain a threshold portion of their mortgages in their own portfolios for the duration of the loans.

Note that the two federal definitions of “community bank” exclude mortgage companies. A focus on portfolio lenders would not exclude mortgage companies by definition. However, the earlier analysis showed that mortgage companies retained only 5 percent of their loan amounts in 2013.

Exhibit 5 below provides summary information comparing the number of lenders using the current statutory criterion for “community bank” with the number of lenders meeting alternative definitions listed above.

| Alternative Ways to Identify a “Community Bank” | Number of Lenders | Value of 1st Lien Residential Mortgage ($Thousands) |

|---|---|---|

| Bank | ||

| Current 10-State Statutory Criterion | 204 | $14,477,792 |

| Federal FRB Definition of Community Bank | 168 | $5,762,401 |

| Federal FDIC Definition of Community Bank | 138 | $3,086,100 |

| Portfolio Lender retains: | ||

|

89 | $2,656,644 |

|

69 | $1,486,014 |

| Mortgage Company | ||

| Current 10-State Statutory Criterion | 48 | $2,334,795 |

| Portfolio Lender retains: | ||

|

2 | $75,091 |

|

2 | $75,091 |

Using publicly available data, Exhibit 6 provides the same information for each of the 252 qualifying institutions.

Click on any column heading to sort the information.

| Institution Name (State) | WA 1st Lien Residential Loans |

Asset Size $10B or Less (FRB Regulatory Definition) |

Community Bank (FDIC Research Definition) |

Amount of Loans Retained |

Percent Retained in Lender Portfolio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homestreet Bank (WA) | $3,142,428 | No | No | $568,109 | 18% |

| Sterling Savings Bank (WA) | $2,318,184 | No | No | $636,875 | 27% |

| Flagstar Bank (MI) | $1,022,878 | Yes | No | $46,232 | 5% |

| Washington Federal (WA) | $670,060 | No | No | $670,060 | 100% |

| USAA Federal Savings Bank (TX) | $626,050 | No | No | $34,604 | 6% |

| Union Bank, N.A. (CA) | $490,413 | No | No | $479,407 | 98% |

| Peoples Bank (WA) | $474,295 | Yes | Yes | $99,552 | 21% |

| Banner Bank (WA) | $431,660 | Yes | No | $122,561 | 28% |

| Umpqua Bank (WA) | $331,749 | No | No | $82,666 | 25% |

| Everbank (FL) | $308,455 | No | No | $63,897 | 21% |

| Washington Trust Bank (WA) | $261,649 | Yes | No | $116,353 | 44% |

| 1st Security Bank of WA (WA) | $259,359 | Yes | Yes | $33,710 | 13% |

| Cole Taylor Bank (IL) | $253,673 | Yes | Yes | $12,085 | 5% |

| The Bank of the Pacific (WA) | $251,488 | Yes | Yes | $37,328 | 15% |

| AmericanWest Bank (WA) | $219,789 | Yes | No | $73,993 | 34% |

| Morgan Stanley Private Bank (NY) | $184,189 | No | No | $163,573 | 89% |

| Colorado Federal Savings (CO) | $172,184 | Yes | No | $5,164 | 3% |

| Whidbey Island Bank (WA) | $163,543 | Yes | Yes | $32,333 | 20% |

| Ally Bank (UT) | $142,851 | No | No | $35,258 | 25% |

| Cashmere Valley Bank (WA) | $139,234 | Yes | Yes | $60,599 | 44% |

| Opus Bank (CA) | $120,768 | Yes | No | $119,328 | 99% |

| Timberland Bank (WA) | $115,773 | Yes | Yes | $45,820 | 40% |

| Sound Community Bank (WA) | $114,362 | Yes | Yes | $41,377 | 36% |

| Luther Burbank Savings (CA) | $111,504 | Yes | No | $111,504 | 100% |

| Yakima Federal S&L (WA) | $110,940 | Yes | Yes | $110,940 | 100% |

| Glacier Bank (MT) | $94,491 | Yes | No | $9,242 | 10% |

| Columbia State Bank (WA) | $92,655 | Yes | No | $92,655 | 100% |

| First Federal Savings Bank (WA) | $75,335 | Yes | Yes | $40,731 | 54% |

| First Savings Bank Northwest (WA) | $70,337 | Yes | Yes | $70,337 | 100% |

| Heritage Bank (WA) | $69,971 | Yes | Yes | $63,185 | 90% |

| State Farm Bank (IL) | $68,183 | No | No | $39,735 | 58% |

| Farmers Bank & Trust Company (KS) | $64,154 | Yes | Yes | $2,563 | 4% |

| Olympia Federal S&L (WA) | $60,150 | Yes | Yes | $60,150 | 100% |

| UBS Bank, USA (UT) | $56,028 | No | No | $56,028 | 100% |

| East West Bank (CA) | $52,974 | No | No | $52,974 | 100% |

| OneWest Bank (CA) | $51,028 | No | No | $205 | 0% |

| First Republic Bank (CA) | $50,918 | No | No | $45,750 | 90% |

| Inland Northwest Bank (WA) | $50,818 | Yes | Yes | $7,520 | 15% |

| North American Savings Bank (MO) | $49,331 | Yes | Yes | $1,918 | 4% |

| National Bank of Kansas City (KS) | $47,284 | Yes | Yes | $843 | 2% |

| Seattle Savings Bank (WA) | $45,598 | Yes | Yes | $0 | 0% |

| Bofi Federal Bank (CA) | $45,588 | Yes | No | $14,876 | 33% |

| BNC National Bank (AZ) | $45,507 | Yes | Yes | $255 | 1% |

| Beech Street Capital LLC (MD) | $45,382 | No | No | $0 | 0% |

| Riverview Community Bank (WA) | $40,566 | Yes | Yes | $17,160 | 42% |

| Baker Boyer National Bank (WA) | $37,440 | Yes | Yes | $3,758 | 10% |

| Proficio Bank (UT) | $35,394 | Yes | Yes | $935 | 3% |

| Kitsap Bank (WA) | $30,027 | Yes | Yes | $14,018 | 47% |

| Third Federal S&L (OH) | $29,471 | No | No | $29,471 | 100% |

| Banc of California, NA (CA) | $27,710 | Yes | No | $130 | 0% |

| BNY Mellon, N.A. (PA) | $26,441 | No | No | $25,291 | 96% |

| Charles Schwab (NV) | $26,430 | No | No | $26,430 | 100% |

| Colonial Savings (TX) | $26,183 | Yes | Yes | $1,752 | 7% |

| Willamette Valley Bank (OR) | $25,289 | Yes | Yes | $0 | 0% |

| Pacific Crest Savings Bank (WA) | $24,908 | Yes | Yes | $24,908 | 100% |

| Coastal Community Bank (WA) | $23,065 | Yes | Yes | $23,065 | 100% |

| Grand Bank (NJ) | $21,864 | Yes | Yes | $4,767 | 22% |

| First Internet Bank of Indiana (IN) | $21,268 | Yes | Yes | $1,333 | 6% |

| Mariner Bank (MD) | $21,138 | Yes | Yes | $486 | 2% |

| Anchor Savings Bank (WA) | $20,260 | Yes | Yes | $14,182 | 70% |

| Capital One, NA (VA) | $20,223 | No | No | $12,356 | 61% |

| Kansas State Bank Of Manhattan (KS) | $20,035 | Yes | Yes | $0 | 0% |

| Boston Private Bank & Trust (MA) | $18,207 | Yes | No | $0 | 0% |

| The Federal Savings Bank (KS) | $16,741 | Yes | Yes | $749 | 4% |

| Goldman Sachs (NY) | $16,552 | No | No | $16,552 | 100% |

| Peoples Bank (KS) | $15,820 | Yes | Yes | $0 | 0% |

| CertusBank, NA (SC) | $15,427 | Yes | No | $0 | 0% |

| Skagit State Bank (WA) | $15,387 | Yes | Yes | $15,387 | 100% |

| Goldwater Bank, N.A. | $14,554 | Yes | Yes | $0 | 0% |

| NCB, FSB (OH) | $14,221 | Yes | Yes | $2,417 | 17% |

| Cathay Bank (CA) | $13,287 | No | No | $10,630 | 80% |

| Business Bank (WA) | $12,746 | Yes | Yes | $12,746 | 100% |

| First Century Bank, N.A. (GA) | $11,724 | Yes | Yes | $0 | 0% |

| Barrington Bank & Trust CO.NA (IL) | $9,521 | Yes | No | $0 | 0% |

| Panhandle State Bank (ID) | $9,397 | Yes | Yes | $6,682 | 71% |

| North Cascades Bank (WA) | $9,317 | No | Yes | $9,317 | 100% |

| West Town Savings Bank (IL) | $8,621 | Yes | Yes | $0 | 0% |

| Grandpoint Bank (CA) | $8,492 | Yes | No | $8,492 | 100% |

| Stifel Bank & Trust (MO) | $8,003 | Yes | No | $417 | 5% |

| First National Bank of Layton (UT) | $7,397 | Yes | Yes | $0 | 0% |

| Mountain Pacific Bank (WA) | $7,384 | Yes | Yes | $7,384 | 100% |

| American Bank (MD) | $7,274 | Yes | Yes | $0 | 0% |

| Bank Of Washington (WA) | $7,215 | Yes | Yes | $7,215 | 100% |

| First Federal Bank, FSB (MO) | $7,090 | Yes | Yes | $672 | 9% |

| First Federal Bank of Florida (FL) | $6,249 | Yes | Yes | $0 | 0% |

| Zions First National Bank (UT) | $5,905 | No | No | $3,481 | 59% |

| Silicon Valley Bank (CA) | $5,606 | No | No | $5,606 | 100% |

| Security State Bank (WA) | $4,969 | Yes | Yes | $4,969 | 100% |

| Community 1st Bank (ID) | $4,852 | Yes | Yes | $4,852 | 100% |

| CBC National Bank (FL) | $4,628 | Yes | Yes | $0 | 0% |

| South Sound Bank (WA) | $3,968 | Yes | Yes | $3,768 | 95% |

| BOKF NA (OK) | $3,963 | No | No | $0 | 0% |

| Raymond James Bank (FL) | $3,915 | No | No | $3,680 | 94% |

| Dubuque Bank & Trust Co. (IA) | $3,762 | Yes | No | $254 | 7% |

| Bank2 (OK) | $3,741 | Yes | Yes | $0 | 0% |

| Access National Bank (VA) | $3,670 | Yes | Yes | $0 | 0% |

| Celtic Bank Corporation (UT) | $3,521 | Yes | No | $0 | 0% |

| Toyota Financial Savings Bank (NV) | $3,303 | Yes | No | $3,303 | 100% |

| Peoples National Bank (CO) | $3,218 | Yes | Yes | $0 | 0% |

| RBC Bank (GEORGIA), NA (GA) | $3,178 | Yes | No | $3,178 | 100% |

| Wheatland Bank (WA) | $3,135 | Yes | Yes | $3,135 | 100% |

| Foundation Bank (WA) | $3,129 | No | No | $3,129 | 100% |

| Prime Pacific Bank, N.A. (WA) | $2,989 | Yes | Yes | $2,989 | 100% |

| Community First Bank (WA) | $2,985 | Yes | Yes | $2,985 | 100% |

| Commerce Bank of Washington (WA) | $2,980 | Yes | No | $2,980 | 100% |

| MBank (OR) | $2,948 | Yes | Yes | $2,468 | 84% |

| The Huntington National Bank (OH) | $2,903 | No | No | $486 | 17% |

| Commerce Bank (MO) | $2,884 | No | No | $2,884 | 100% |

| Puget Sound Bank (WA) | $2,795 | Yes | Yes | $2,795 | 100% |

| Heartland Bank (MO) | $2,679 | Yes | Yes | $685 | 26% |

| Pacific Mercantile Bank (CA) | $2,674 | Yes | No | $0 | 0% |

| Compass Bank (AL) | $2,607 | Yes | Yes | $2,397 | 92% |

| Bank of Fairfield (WA) | $2,433 | Yes | Yes | $2,433 | 100% |

| Riverbank (WA) | $2,339 | Yes | Yes | $2,339 | 100% |

| Fife Commercial Bank (WA) | $2,333 | Yes | Yes | $2,333 | 100% |

| Pacific Continental Bank (OR) | $2,225 | Yes | Yes | $2,225 | 100% |

| Idaho Independent Bank (ID) | $2,150 | Yes | Yes | $154 | 7% |

| Regal Financial Bank (WA) | $2,085 | Yes | Yes | $2,085 | 100% |

| State Bank Northwest (WA) | $1,886 | Yes | Yes | $1,886 | 100% |

| Barclays Bank Delaware (DE) | $1,820 | No | No | $1,820 | 100% |

| Commencement Bank (WA) | $1,819 | Yes | Yes | $1,819 | 100% |

| Bank of Manhattan (CA) | $1,811 | Yes | No | $0 | 0% |

| Lewis & Clark Bank (OR) | $1,799 | Yes | Yes | $1,799 | 100% |

| The National Bank (IL) | $1,739 | Yes | Yes | $0 | 0% |

| Liberty Bay Bank (WA) | $1,738 | Yes | Yes | $1,738 | 100% |

| Capital Bank, NA (MD) | $1,695 | Yes | Yes | $0 | 0% |

| Georgia Banking Company (GA) | $1,475 | Yes | Yes | $0 | 0% |

| Century Bank, NA (CA) | $1,300 | Yes | Yes | $1,300 | 100% |

| BBCN Bank (CA) | $1,300 | Yes | No | $1,300 | 100% |

| Washington Business Bank (WA) | $1,178 | Yes | Yes | $1,178 | 100% |

| The PrivateBank and Trust Co. (IL) | $1,151 | No | No | $0 | 0% |

| Twin City Bank (WA) | $1,098 | Yes | Yes | $1,098 | 100% |

| Twin River National Bank (WA) | $1,042 | Yes | Yes | $1,042 | 100% |

| Legacy Bank (OK) | $1,007 | Yes | Yes | $1,007 | 100% |

| Community Bank (OR) | $1,005 | Yes | Yes | $1,005 | 100% |

| Nationwide Bank (OH) | $1,003 | Yes | Yes | $1,003 | 100% |

| Sterling National Bank (NY) | $1,001 | Yes | Yes | $0 | 0% |

| Alerus Financial, N.A. (ND) | $986 | Yes | Yes | $0 | 0% |

| First State Bank of St Charles (MO) | $963 | Yes | Yes | $0 | 0% |

| Regents Bank, N.A. (CA) | $946 | No | No | $946 | 100% |

| Greenchoice Bank, FSB (IL) | $918 | Yes | Yes | $0 | 0% |

| Astoria Federal Savings & Loan (NY) | $860 | No | No | $860 | 100% |

| Bank of Blue Valley (KS) | $842 | Yes | Yes | $0 | 0% |

| Allied First Bank, SB (IL) | $813 | Yes | Yes | $0 | 0% |

| Mountain West Bank, N.A. (MT) | $809 | Yes | Yes | $0 | 0% |

| First Choice Bank (NJ) | $799 | Yes | Yes | $135 | 17% |

| Stockman Bank of Montana (MT) | $769 | Yes | Yes | $769 | 100% |

| Bank of Utah (UT) | $769 | Yes | Yes | $0 | 0% |

| Canyon Community Bank, NA (AZ) | $716 | Yes | Yes | $0 | 0% |

| Prime Bank (IA) | $711 | Yes | Yes | $711 | 100% |

| American B & T C N.A. (IA) | $687 | Yes | Yes | $475 | 69% |

| UMB Bank NA (MO) | $687 | No | No | $545 | 79% |

| Comerica Bank (TX) | $675 | No | No | $675 | 100% |

| Albina Community Bank (OR) | $630 | Yes | Yes | $630 | 100% |

| EagleBank (MD) | $585 | Yes | Yes | $0 | 0% |

| Golden Pacific Bank, NA (CA) | $584 | Yes | Yes | $0 | 0% |

| Bank of American Fork (UT) | $573 | Yes | Yes | $0 | 0% |

| Mutual of Omaha Bank (NE) | $565 | Yes | No | $0 | 0% |

| Oregon Pacific Bank (OR) | $528 | Yes | Yes | $355 | 67% |

| MWA Bank (IL) | $528 | Yes | Yes | $528 | 100% |

| HBank Texas (TX) | $525 | Yes | Yes | $525 | 100% |

| Wolverine Bank FSB (MI) | $506 | Yes | Yes | $0 | 0% |

| Syringa Bank (ID) | $459 | Yes | Yes | $0 | 0% |

| First National Bank of Layton (UT) | $417 | Yes | Yes | $0 | 0% |

| Illinois National Bank (IL) | $417 | Yes | Yes | $0 | 0% |

| Oakstar Bank (MO) | $417 | Yes | Yes | $0 | 0% |

| Great Western Bank (SD) | $412 | Yes | No | $412 | 100% |

| Millennium Bank (IL) | $401 | Yes | Yes | $0 | 0% |

| Central Trust Bank (MO) | $376 | Yes | No | $376 | 100% |

| Union Savings Bank (IL) | $372 | Yes | No | $0 | 0% |

| Nexbank SSB (TX) | $368 | Yes | Yes | $368 | 100% |

| Presidential Bank (ND) | $364 | Yes | Yes | $0 | 0% |

| First Merchants Bank, NA (IN) | $357 | Yes | No | $0 | 0% |

| American Midwest Bank (IL) | $354 | Yes | Yes | $0 | 0% |

| Grand Bank (TX) | $352 | Yes | Yes | $0 | 0% |

| Cache Valley Bank (UT) | $342 | Yes | Yes | $0 | 0% |

| Bank of The Cascades (OR) | $340 | Yes | Yes | $340 | 100% |

| TIB The Independent Bankers Bank (TX) | $339 | Yes | No | $0 | 0% |

| Santander Bank N.A. (DE) | $334 | No | No | $0 | 0% |

| Commercial Bank of Texas, N.A. (TX) | $320 | Yes | Yes | $0 | 0% |

| The First Bexley Bank (OH) | $320 | Yes | Yes | $0 | 0% |

| Landmark Bank (MO) | $302 | Yes | Yes | $0 | 0% |

| Cross River Bank (NJ) | $302 | Yes | Yes | $0 | 0% |

| FirstOak Bank (KS) | $268 | Yes | Yes | $0 | 0% |

| The Citizens National Bank (OH) | $236 | Yes | Yes | $0 | 0% |

| Bank'34 (NM) | $217 | Yes | Yes | $0 | 0% |

| Carrollton Bank (IL) | $210 | Yes | Yes | $0 | 0% |

| First Montana Bank (MT) | $203 | Yes | Yes | $203 | 100% |

| First Federal Savings Bank (WA) | $195 | Yes | Yes | $0 | 0% |

| North Valley Bank (CA) | $194 | Yes | Yes | $0 | 0% |

| People's Bank of Commerce (OR) | $191 | Yes | Yes | $0 | 0% |

| Citizens Bank Minnesota (MN) | $186 | Yes | Yes | $0 | 0% |

| First National Bank (SD) | $181 | Yes | Yes | $181 | 100% |

| Bank of Canton (MA) | $150 | Yes | Yes | $150 | 100% |

| MidFirst Bank (OK) | $142 | Yes | No | $142 | 100% |

| Main Bank (NM) | $130 | Yes | Yes | $0 | 0% |

| First National Bank of America (MI) | $123 | Yes | Yes | $0 | 0% |

| Midwest Bank (MN) | $112 | Yes | Yes | $112 | 100% |

| First State Bank (IL) | $110 | Yes | Yes | $0 | 0% |

| 1st Constitution Bank (NJ) | $107 | Yes | Yes | $0 | 0% |

| Five Points Bank (NE) | $93 | Yes | Yes | $93 | 100% |

| Bank of Whittier, NA (CA) | $83 | Yes | Yes | $83 | 100% |

| Bank of Stockton (CA) | $80 | Yes | Yes | $80 | 100% |

| Mohave State Bank (AZ) | $55 | Yes | Yes | $0 | 0% |

| Evergreen Moneysource Mortgage (WA) | $455,141 | NA | NA | $21,236 | 5% |

| Mortgage Master Service Corp (WA) | $230,182 | NA | NA | $490 | 0% |

| Directors Mortgage Inc. (OR) | $227,117 | NA | NA | $6,301 | 3% |

| Mortgage Investors Corp (FL) | $200,732 | NA | NA | $885 | 0% |

| Mortgage Broker Services Inc. (WA) | $170,496 | NA | NA | $0 | 0% |

| Roundpoint Mortgage Company (NC) | $115,346 | NA | NA | $395 | 0% |

| Summit Mortgage Corporation (OR) | $111,345 | NA | NA | $0 | 0% |

| Network Mortgage Services (WA) | $101,448 | NA | NA | $0 | 0% |

| Westwood Mortgage, Inc. (WA) | $76,506 | NA | NA | $506 | 1% |

| Northwest Mortgage Alliance (WA) | $50,987 | NA | NA | $50,987 | 100% |

| Wallick and Volk, Inc. (WY) | $50,591 | NA | NA | $0 | 0% |

| First Financial Services, Inc. (NC) | $50,327 | NA | NA | $0 | 0% |

| First Priority Financial Inc. (CA) | $46,141 | NA | NA | $243 | 1% |

| Mortgage Express, LLC (OR) | $38,810 | NA | NA | $0 | 0% |

| Northwest Mortgage Group, Inc. (OR) | $36,649 | NA | NA | $0 | 0% |

| Military Family Home Loans, LLC (IA) | $31,533 | NA | NA | $10,014 | 32% |

| Pacific Residential Mortgage (OR) | $30,432 | NA | NA | $0 | 0% |

| LPMC LLC (OR) | $30,360 | NA | NA | $216 | 1% |

| American Southwest Mortgage (OK) | $26,326 | NA | NA | $506 | 2% |

| Central Banc Mortgage (WA) | $24,986 | NA | NA | $0 | 0% |

| Equity Home Mortgage, LLC (OR) | $24,104 | NA | NA | $24,104 | 100% |

| Residential Mortgage, LLC (AK) | $24,067 | NA | NA | $0 | 0% |

| American Interbanc (CA) | $20,565 | NA | NA | $0 | 0% |

| Premier Mortgage Resources LLC (OR) | $20,507 | NA | NA | $1,050 | 5% |

| Shea Mortgage Inc. (AZ) | $18,679 | NA | NA | $2,016 | 11% |

| Golden Empire Mortgage Inc. (CA) | $17,560 | NA | NA | $0 | 0% |

| Residential Finance Corp (OH) | $16,952 | NA | NA | $0 | 0% |

| University Islamic Financial (MI) | $15,319 | NA | NA | $202 | 1% |

| Mortgage Trust, Inc. (OR) | $15,119 | NA | NA | $0 | 0% |

| Crossline Capital Inc. (CA) | $12,688 | NA | NA | $0 | 0% |

| HighTechLending Inc. (CA) | $12,301 | NA | NA | $0 | 0% |

| Legacy Group Capital LLC (WA) | $8,189 | NA | NA | $0 | 0% |

| South Pacific Financial Corporation (CA) | $4,522 | NA | NA | $0 | 0% |

| Community Mortgage Funding (CA) | $3,968 | NA | NA | $1,352 | 34% |

| Affiliated Mortgage Company (LA) | $3,363 | NA | NA | $386 | 11% |

| LHM Financial Corporation (AZ) | $3,006 | NA | NA | $0 | 0% |

| Summit Mortgage Corporation (MN) | $2,424 | NA | NA | $417 | 17% |

| JMAC Lending, Inc. (CA) | $1,528 | NA | NA | $0 | 0% |

| Manhattan Financial Group, Inc. (CA) | $820 | NA | NA | $0 | 0% |

| Allen Mortgage LC (AR) | $655 | NA | NA | $0 | 0% |

| JFK Financial Inc. (NV) | $548 | NA | NA | $0 | 0% |

| Mountain west financial, Inc. (CA) | $501 | NA | NA | $0 | 0% |

| A. K. T. American Capital, Inc. (CA) | $482 | NA | NA | $0 | 0% |

| Coast 2 Coast Funding Group (CA) | $390 | NA | NA | $0 | 0% |

| Sacramento 1st Mortgage, Inc. (CA) | $363 | NA | NA | $0 | 0% |

| BM Real Estate Services Inc. (CA) | $283 | NA | NA | $0 | 0% |

| American Lending (CA) | $260 | NA | NA | $0 | 0% |

| Veritas Funding (UT) | $177 | NA | NA | $0 | 0% |

What are the past and future tax revenue and economic impacts of the tax preference to the taxpayer and to the government if it is continued?

JLARC staff estimated the beneficiary savings for this preference by matching records from DOR, federal Home Loan Disclosure Act (HMDA) data, Call and Thrift Reports from the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC), and data from the Conference of State Bank Supervisors (CSBS). Deduction detail from DOR tax returns is incomplete and must be supplemented with HMDA data which provides information on first lien residential mortgages originated in Washington identified by lender. FFIEC Call and Thrift Reports provide information on depository institutions that operate in 10 or fewer states. The CSBS provides information on mortgage companies making mortgage loans in Washington and that operate in 10 or fewer states.

The beneficiaries of the preference, including banks and mortgage companies, saved an estimated at $23 million in Fiscal Year 2014 and will save an estimated $49.8 million in the 2015-17 Biennium. See Exhibit 7 below.

| Fiscal Year | Depository Institutions | Mortgage Companies | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | $24,144,000 | $2,242,000 | $26,386,000 |

| 2013 | $21,247,000 | $1,973,000 | $23,220,000 |

| 2014 | $21,074,000 | $1,957,000 | $23,031,000 |

| 2015 | $21,379,000 | $1,985,000 | $23,365,000 |

| 2016 | $22,251,000 | $2,066,000 | $24,317,000 |

| 2017 | $23,272,000 | $2,161,000 | $25,433,000 |

| 2015-17 Biennium |

$45,523,000 | $4,227,000 | $49,750,000 |

If the tax preference were to be terminated, what would be the negative effects on the taxpayers who currently benefit from the tax preference and the extent to which the resulting higher taxes would have an effect on employment and the economy?

If the tax preference were terminated, lenders would have to pay B&O tax on the interest received from loans for first lien mortgages.

Lenders that retain a larger portion of their loans in their own portfolios could be affected more than lenders that sell their loans. Lenders that retain portfolio loans would not be able to restructure existing loans on their books. Some of these loans lock in interest rates for long periods and cannot be adjusted for the loss of the deduction. Representatives of the banking industry testified to the Legislature that portfolio lenders might need to increase interest rates or decrease residential loans if the preference were terminated.

It is not known how loan availability and Washington’s housing market would be impacted by this change given that Washington’s housing market appears to follow national trends.

Do other states have a similar tax preference and what potential public policy benefits might be gained by incorporating a corresponding provision in Washington?

States imposing a personal income tax have the ability to allow a mortgage interest deduction that provides tax relief directly to the homeowner. Washington has no personal income tax and instead provides tax relief to the mortgage lender.

Washington is the only state to offer a deduction from state taxes for income derived from interest on loans secured by first mortgages or trust deeds. West Virginia has a similar deduction for municipal business and occupation taxes. Almost all other states use net income or net worth to tax financial institutions and do not provide a deduction for mortgage interest.

Of the 41 states that impose a personal income tax, 31 allow a deduction for interest paid on mortgages for homeowners that itemize deductions.

RCW 82.04.4292

Deductions - Interest on investments or loans secured by mortgages or deeds of trust.

(1) In computing tax there may be deducted from the measure of tax by those engaged in banking, loan, security or other financial businesses, interest received on investments or loans primarily secured by first mortgages or trust deeds on nontransient residential properties.

(2) Interest deductible under this section includes the portion of fees charged to borrowers, including points and loan origination fees, that is recognized over the life of the loan as an adjustment to yield in the taxpayer's books and records according to generally accepted accounting principles.

(3) Subsections (1) and (2) of this section notwithstanding, the following is a nonexclusive list of items that are not deductible under this section:

(a) Fees for specific services such as: Document preparation fees; finder fees; brokerage fees; title examination fees; fees for credit checks; notary fees; loan application fees; interest lock-in fees if the loan is not made; servicing fees; and similar fees or amounts;

(b) Fees received in consideration for an agreement to make funds available for a specific period of time at specified terms, commonly referred to as commitment fees;

(c) Any other fees, or portion of a fee, that is not recognized over the life of the loan as an adjustment to yield in the taxpayer's books and records according to generally accepted accounting principles;

(d) Gains on the sale of valuable rights such as service release premiums, which are amounts received when servicing rights are sold; and

(e) Gains on the sale of loans, except deferred loan origination fees and points deductible under subsection (2) of this section, are not to be considered part of the proceeds of sale of the loan.

(4) Notwithstanding subsection (3) of this section, in computing tax there may be deducted from the measure of tax by those engaged in banking, loan, security, or other financial businesses, amounts received for servicing loans primarily secured by first mortgages or trust deeds on nontransient residential properties, including such loans that secure mortgage-backed or mortgage-related securities, but only if:

(a)(i) The loans were originated by the person claiming a deduction under this subsection (4) and that person either sold the loans on the secondary market or securitized the loans and sold the securities on the secondary market; or

(ii)(A) The person claiming a deduction under this subsection (4) acquired the loans from the person that originated the loans through a merger or acquisition of substantially all of the assets of the person who originated the loans, or the person claiming a deduction under this subsection (4) is affiliated with the person that originated the loans. For purposes of this subsection, "affiliated" means under common control. "Control" means the possession, directly or indirectly, of more than fifty percent of the power to direct or cause the direction of the management and policies of a person, whether through the ownership of voting shares, by contract, or otherwise; and

(B) Either the person who originated the loans or the person claiming a deduction under this subsection (4) sold the loans on the secondary market or securitized the loans and sold the securities on the secondary market; and

(b) The amounts received for servicing the loans are determined by a percentage of the interest paid by the borrower and are only received if the borrower makes interest payments.

(5) The deductions provided in this section do not apply to persons subject to tax under RCW 82.04.29005.

(6) By June 30, 2015, the joint legislative audit and review committee must review the deductions provided in this section in accordance with RCW 43.136.055 and make a recommendation as to whether the deductions should be continued without modification, modified, or terminated immediately.

[2012 2nd sp.s. c 6 § 102; 2010 1st sp.s. c 23 § 301; 1980 c 37 § 12. Formerly RCW 82.04.430(11).]

RCW 82.04.29005

Tax on loan interest - 2012 2nd sp.s. c 6.

(1) Amounts received as interest on loans originated by a person located in more than ten states, or an affiliate of such person, and primarily secured by first mortgages or trust deeds on nontransient residential properties are subject to tax under RCW 82.04.290(2)(a).

(2) For the purposes of this subsection [section], a person is located in a state if:

(a) The person or an affiliate of the person maintains a branch, office, or one or more employees or representatives in the state; and

(b) Such in-state presence allows borrowers or potential borrowers to contact the branch, office, employee, or representative concerning the acquiring, negotiating, renegotiating, or restructuring of, or making payments on, mortgages issued or to be issued by the person or an affiliate of the person.

(3) For purposes of this section:

(a) "Affiliate" means a person is affiliated with another person, and "affiliated" has the same meaning as in RCW 82.04.645; and

(b) "Interest" has the same meaning as in RCW 82.04.4292 and also includes servicing fees described in RCW 82.04.4292(4).

[2012 2nd sp.s. c 6 § 101.]

- Legislative Auditor Recommendation

- Commissioners’ Recommendation

- Letter from Commission Chair

- Agency Response

Legislative Auditor Recommendation 1: Review and Clarify

The Legislature should review the detailed information on the lenders that make loans that qualify for the preference compared to other “community bank” definitions and determine whether the preference is focused on the pool of lenders the Legislature intended.

In its 2012 deliberations, the Legislature indicated it wanted to limit the preference to lenders that were “community banks.” Potential violation of the federal Commerce Clause was a concern. The Legislature chose to identify community banks as lenders located in 10 or fewer states.

If the Legislature determines after its review of qualifying institutions that this is not the lending pool it intended, this review provides other options for identifying “community banks” that may avoid Commerce Clause concerns. Options include using either of two federal definitions of “community bank” or focusing on lenders that retain a threshold portion of their loans in their own portfolios. Identifying community banks using one of these other options would further limit the pool of qualifying lenders.

Legislation Required: Yes.

Fiscal Impact: Depends on legislative action.

Legislative Auditor Recommendation 2: Review and Clarify

The Legislature should review and clarify the public policy objective of the mortgage interest deduction because the original inferred public policy objective of stimulating the residential housing market may no longer apply given the changes in the lending industry and the rise of the secondary mortgage market.

Evidence presented in this year’s review indicates that:

- Qualifying lenders sell more than two-thirds of their loan amounts within one year of the loan origination;

- Borrowers use qualifying loans more for uses such as refinancing than for purchasing homes; and

- Washington housing starts follow national trends and appear not to be driven by local factors.

The Legislative Auditor’s guidance document for drafting performance statements provides a framework for identifying policy objectives and linking these to performance metrics.

Legislation Required: Yes.

Fiscal Impact: Depends on legislative action.

The Commission does not endorse the Legislative Auditor’s recommendation and recommends that the Legislature should maintain the 2012 legislation defining which lenders qualify for the preference.

Washington State financial institutions that portfolio mortgage loans compete with their counterparts in other states who are subject to different tax regimes. The industry’s testimony made the reasonable argument that the current tax preference helps mitigate the competitive disadvantage created by recent federal regulatory changes. In this new environment, smaller financial institutions are struggling to absorb the increase in regulatory costs associated with lending. Although offsetting regulatory costs was not the preference’s original stated intent, the preference appears to enable smaller financial firms to compete with (1) large nationally-based financial firms whose size enables them to absorb these additional costs and (2) credit unions, which have special tax status. Indicative of increased cost pressures facing smaller community banks, the number of community banks nationally has fallen from about 7,000 in 2008 to 5,400 recently (a 23% decline). Over this same time period, the number of commercial banks headquartered in Washington State has declined from 81 to 45 (a 44% decline). While there are many factors driving shrinkage in the number of community banks, limiting the current preference in same fashion could aggravate that trend.

Furthermore, the inferred public policy objectives do not capture the legislative debate and compromise that surrounded the compromise reached to determine the class and type of banks that would continue to qualify for the exemption. Specifically, the current testimony and debate at the time of the 2012 legislation indicated the restructuring of the exemption was to provide a benefit to a certain population of smaller, local lending institutions without violating commerce clause restrictions imposed by the courts. The community bank definitions considered by JLARC staff were not adopted during legislative debate of these provisions because they would not have encompassed the full population of banks the Legislature determined should be covered.