This technical appendix provides background detail and supporting information for the

JLARC staff analysis of the employment impacts associated with Washington's sales and

use tax deferral for investment projects in high unemployment counties and CEZs. The

appendix is divided into three sections:

- Section One titled REMI Methodology details how JLARC staff set up and

calibrated the Tax-PI program prior to using the model.

- Section Two titled Jobs for the Manufacturing Industries in REMI discusses

baseline manufacturing employment in the REMI model of the Washington economy, and

the observed increase in employment at business sites where beneficiaries have used

the preference.

- Section Three titled Modeling the Impact of the Sales and Use Tax Deferral for

the Manufacturing Industry in REMI describes the scenarios used to estimate

the range of potential employment effects of the sales and use tax deferral on

statewide employment. The results of this analysis are presented in the "Are

Objectives Being Met?" tab.

1) REMI Methodology

User Inputs in REMI

REMI's Tax-PI model allows users to model policy changes and analyze the estimated

impacts to the Washington economy, both in terms of economic activity and government

finances. (See Technical Appendix 1 for an overview of the REMI model.)

Prior to running modeling scenarios, users must make a series of choices about how to

set up the modeling environment by building a state budget and calibrating the model

accordingly. JLARC staff used the November 2017 revenue estimates produced by the

Economic and Revenue Forecast Council (ERFC) and budgeted expenditures for fiscal

years 2016 and 2017, as reported by the Legislative Evaluation and Accountability

Program (LEAP) Committee. This data represents the budget and revenue data in the

model and serves as the "jump off" point for Tax-PI's economic and fiscal estimates.

Because Tax-PI is a forecasting tool, JLARC staff was unable to model the economic

impact of the tax preference beginning in 2010.

In addition to establishing a budget and inputting expected revenue values, users

must specify whether government expenditures are determined by demand or revenue. "By

demand" imposes a level of government spending in future years that is necessary to

maintain the same level of service as the final year in which budget data is entered.

"By revenue" ties government expenditures to estimated changes in revenue collections.

Users may also elect to impose a balanced budget restriction or leave the model

unconstrained. The balanced budget feedback forces revenue and expenditures to be

equivalent and thus may impose some limitations on economic activity.

By setting expenditures to be determined by demand, users avoid making assumptions

about how policymakers may alter spending priorities in the future. In addition, users

essentially establish the current budget allocation as carry-forward levels for each

expenditure category.

JLARC staff ran the reported scenarios with expenditures set to be determined by

demand and with the balanced budget feedback option turned on.

Data for the REMI Model

The REMI model comes with historical economic and demographic data back to 1990. The

data comes from federal government agencies such as the U.S. Census Bureau, U.S.

Energy Information Administration, the Bureau of Labor Statistics, and the Bureau of

Economic Analysis. As described above, current revenue and expenditure data for

Washington comes from ERFC and LEAP, respectively. The data to build the modeling

scenario described in section three is from JLARC staff estimations of beneficiary

savings, based on Department of Revenue tax records.

2) Jobs for the Manufacturing Industries in REMI

The majority of businesses that claim the deferral report North American Industry

Classification System (NAICS) numbers identifying them as primarily manufacturing

businesses. Therefore, JLARC staff modeled the potential employment effects of the

preference on baseline employment of businesses in the manufacturing industry (NAICS

31 - 33).

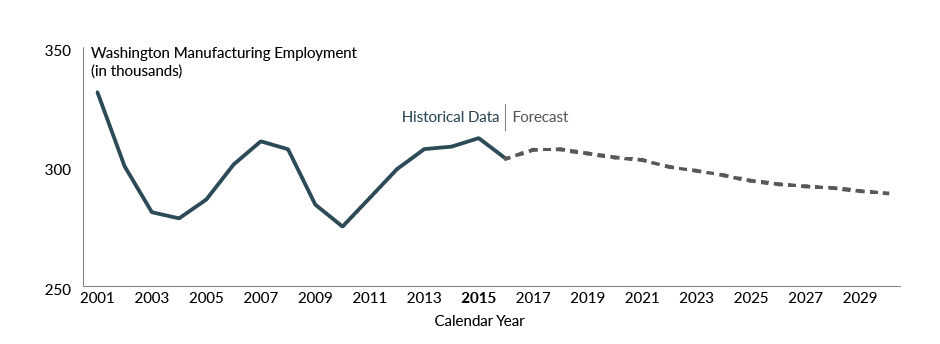

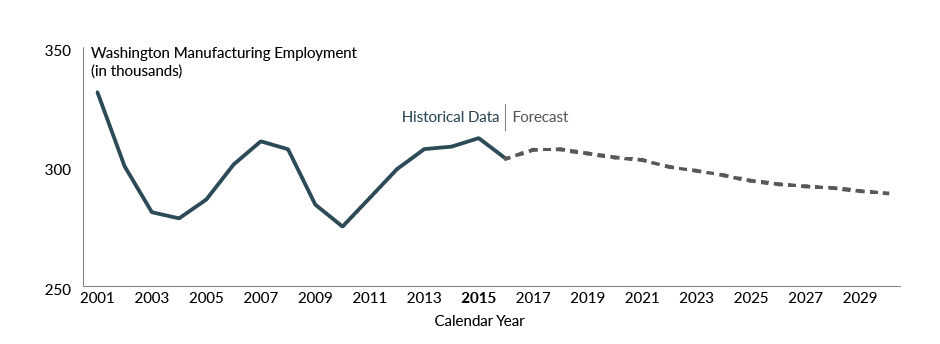

Manufacturing Industry Jobs Fluctuated in Washington between 2001 and 2015

REMI's historical baseline forecast employment data for the manufacturing industry

fluctuated from a high of 331,000 in 2001 to a low of 275,000 in 2010. Employment is

projected to decline steadily from 312,000 in 2015 to 289,000 in 2030.

Exhibit: REMI Baseline and Forecast Data Shows Statewide Manufacturing Jobs Decline

after 2015

Source: JLARC staff analysis of REMI data for jobs using NAICS codes for

manufacturing (31 - 33).

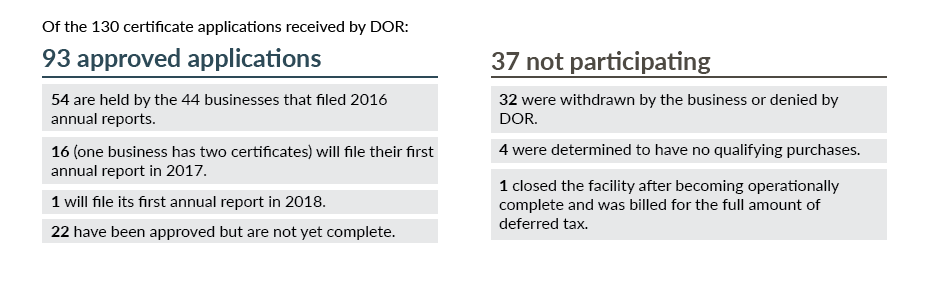

Beneficiaries of the Tax Preference Report 131 New Jobs at Qualifying Sites

Data reported to the Department of Revenue shows the 44 businesses that claimed the

preference in 2016 increased employment by 131 during 2010-2016, the years the tax

preference has been in effect.

3) Modeling the Impact of the Sales and Use Tax Deferral for Investment Projects in

High Unemployment Counties and CEZs

JLARC staff followed a two-step approach to modeling the employment impacts of the

tax preference:

- Increased employment in all manufacturing sectors included in the REMI model.

- Reduced government spending by an amount equivalent to the taxpayer savings.

JLARC staff modeled three scenarios that illustrate the range of potential employment

effects that result from the tax preference. JLARC staff are unable to determine how

many of the 131 jobs created at the manufacturing sites of beneficiary businesses were

created directly as a result of the preference. Instead, JLARC staff attempted to

illustrate lower and upper bounds of potential employment effects based on two

assumptions for the share of reported jobs that were directly created as a result of

the preference, as well as the point at which the positive employment effects of

additional manufacturing employment offset the negative employment effects of reduced

government spending.

For each scenario modeled, JLARC staff modeled a change in nominal state government

spending in the amount of the estimated beneficiary savings for FY 2016-2030.These

amounts are shown below:

|

Fiscal Year

|

Estimated Beneficiary Savings

|

|

2016

|

1,203,669

|

|

2017

|

1,631,488

|

|

2018

|

2,046,273

|

|

2019

|

2,461,059

|

|

2020

|

2,875,844

|

|

2021

|

2,875,844

|

|

2022

|

2,876,000

|

|

2023

|

2,876,000

|

|

2024

|

2,876,000

|

|

2025

|

2,876,000

|

|

2026

|

2,461,000

|

|

2027

|

2,046,000

|

|

2028

|

1,632,000

|

|

2029

|

1,217,000

|

|

2030

|

802,000

|

Scenario 1: Beneficiary Savings Induce No Change in Manufacturing Sector

In the first scenario, JLARC staff assumed none of the 131 new jobs were

created directly due to the preference. This scenario assumes no manufacturing

employment change from the baseline, and includes only the direct, indirect, and

induced employment effects of the change in state government spending.

Scenario 2: Beneficiary Savings Induce Reported Job Increases at Manufacturing

Sites

In the second scenario, JLARC staff assumed all of the 131 new jobs were

created directly due to the preference. This scenario assumes the manufacturing

employment change from the baseline of 131 jobs, distributed among the 75

manufacturing subsectors in the REMI model, weighted by each subsector's relative

output level. The employment changes are applied at the firm (competes locally) level.

Scenario 3: Beneficiary Savings Induce Some Job Increases at Manufacturing Sites, No

Net Employment Change in 2016

In the third scenario, JLARC staff assumed just enough of the 131 new jobs

were created directly due to the preference to offset the employment losses resulting

from the reduction in government spending. This scenario involved running REMI

scenarios with incrementally increasing manufacturing employment changes until the

2016 employment change from the baseline was zero. In each case, the manufacturing

employment change from the baseline was distributed among the 75 manufacturing

subsectors in the REMI model, weighted by each subsector's relative output level. The

employment changes are applied at the firm (competes locally) level.

JLARC staff used REMI to model how this direct employment change and its indirect and

induced effects offset the direct, indirect, and induced employment effects of the

change in state government spending.

Exhibit: Three Scenarios Illustrate Range of Possible Statewide Employment Effects

of Tax Preference

|

Scenario #

|

Description

|

2016

|

2017

|

2018

|

2019

|

2020

|

2021

|

|

1

|

Beneficiary Savings Induce No Change in Manufacturing Sector

|

-29

|

-40

|

-51

|

-59

|

-65

|

-62

|

|

2

|

Beneficiary Savings Induce Reported Job Increases at Manufacturing Sites

|

429

|

455

|

539

|

532

|

516

|

503

|

|

3

|

Beneficiary Savings Induce Some Job Increases at Manufacturing Sites, No Net

Employment Change in 2016

|

0

|

-8

|

-12

|

-20

|

-28

|

-26

|

Source: JLARC staff analysis on future year possible employment changes using REMI

economic modeling tool.

Two Employment Data Sources

Different Approaches in Reporting Employment

The employment and wage numbers used in the main report are from administrative data

collected and maintained by the Washington Employment Security Department (ESD) and

reported to the U.S. Department of Labor's Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). This data

captures workers covered by state unemployment insurance and federal workers covered

by unemployment compensation for federal employees. It omits some workers in the labor

market, including self-employed and sole proprietors.

The REMI model, on the other hand, uses employment data from the U.S. Department of

Commerce's Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). BEA makes a number of adjustments to

employment and wage data for occupations not covered by the BLS system (see BEA's Frequently Asked

Questions for further details).

Understanding the distinction between BEA and BLS employment data is important for

two reasons. First, the BEA jobs numbers tend to be higher, as they capture a wider

selection of employment, including sole proprietors. However, it may count a person

holding multiple jobs as a number greater than one, whereas the BLS data counts a

person one time regardless of the number of jobs performed. Second, while BEA provides

a more comprehensive picture, it has an approximate two-year lag behind BLS data,

which is regularly updated throughout the year and receives more attention in the

press. According to REMI, BEA employment data operates as a unit of demand related to

the tasks a worker performs within a job, rather than a job itself.

❮ Previous

Next ❯

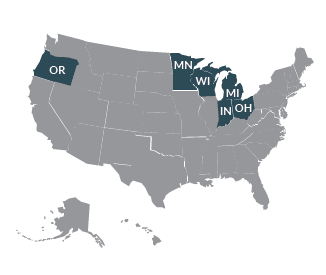

JLARC staff reviewed economic development tax incentive programs offered in top

manufacturing states as well as Idaho and Oregon, two neighboring states. Staff

focused on leading manufacturing states because the majority of beneficiaries of this

preference are manufacturers. In 2016, the five states with the greatest concentration

of manufacturing jobs were Michigan, Wisconsin, Ohio, Indiana, and Minnesota.

JLARC staff reviewed economic development tax incentive programs offered in top

manufacturing states as well as Idaho and Oregon, two neighboring states. Staff

focused on leading manufacturing states because the majority of beneficiaries of this

preference are manufacturers. In 2016, the five states with the greatest concentration

of manufacturing jobs were Michigan, Wisconsin, Ohio, Indiana, and Minnesota.