WSDOT Can Provide Reliable Long-Term Pavement Estimates, but Accuracy of Bridge Estimates Is Uncertain

Final Report 14-5, January 2015

This is the second of two reports required by the Legislature to review the methods and systems the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) uses to develop long-term estimates of maintenance and preservation needs. In this second phase, JLARC contracted with expert consultants to review how WSDOT estimates future needs for highway pavement and bridges. They found that WSDOT:

- Maintains accurate data for pavement and bridges.

- Can provide reliable long-term (10-year) estimates for pavement maintenance and preservation.

- Did not use best practices to develop long-term estimates for bridge maintenance and preservation needs, so the consultants could not verify the accuracy of the bridge estimates.

The Legislative Auditor offers recommendations to improve WSDOT’s bridge estimates and to develop a process to improve stakeholders’ confidence and understanding of how WSDOT develops its estimates.

JLARC’s consultants identified key components that should be included in a 10-year estimate of maintenance and preservation needs. These components, as well as WSDOT’s ability to provide them, are summarized below.

WSDOT's capacity for  |

WSDOT's capacity for |

|

| Expected asset deterioration | Yes | Partial. Estimated for steel coating systems and short term concrete deck deterioration. |

| Expected effectiveness of maintenance and preservation work | Yes | Partial. With a few exceptions, effectiveness of maintenance and preservation work not measured. |

| Investment options and predicted conditions based on different funding scenarios | Yes | No. Predicted condition is not based on validated, quantitative analysis of bridge deterioration and the effectiveness of alternative treatments. |

| Investment recommendations based on life cycle cost analysis | Yes | No |

| Risk | Yes | Partial |

Bottom line |

Reliable. Developed using industry best practices. |

JLARC’s consultants could not verify accuracy. Estimates were not developed using best practices. WSDOT’s estimate may be:

|

Friendly

In Brief

The Legislature directed JLARC to review the methods and systems the Department of Transportation (WSDOT) uses to develop cost estimates for highway maintenance and preservation needs. Our review focuses on state highway pavement and bridges.

WSDOT’s cost estimates for long-term pavement needs are reliable. The agency’s cost estimates for long-term bridges needs, need improvement. WSDOT could help ensure stakeholder confidence in its cost estimates for both pavement and bridges by establishing a routine and consistent cost estimating process.

Legislative Auditor Recommends:

-

1: Improve bridge estimates

WSDOT should use best practices to make its bridge estimates as reliable as its pavement estimates.JLARC’s consultant notes that every state that uses its bridge management system effectively has required several years of incremental changes, and expects that WSDOT will be no different. Therefore, developing a multi-year plan of implementing recommendations is a key first step.

- Develop implementation plan. WSDOT should develop and report its plan to improve the reliability of its long-term bridge estimates to the appropriate Legislative committees by June 30, 2015.

- Identify near term actions. While fully implementing the recommendations from this report will be a multi-year process, there are several actions that WSDOT can complete in the short-term to improve the accuracy of its long-term bridge estimates. Examples include developing:

- Deterioration models and cost models;

- Preliminary estimates of life cycle costs and construct a preservation plan which minimizes life cycle cost;

- A list of bridges that are most vulnerable to natural and man-made hazards, and the Department’s plans to report regularly on its progress reducing risk.

- Identify longer-term actions. These actions include acquiring or developing a bridge management system, and determining when these actions will be completed and what, if any, cost is associated with doing so.

Legislation Required: None Fiscal Impact: None Implementation Date: June 30, 2015 -

2: Document and communicate

WSDOT and OFM should develop a process to improve stakeholders’ confidence in its highway estimates.JLARC’s report identifies best practices that contribute to a confidence-building forecasting and estimating process. These include:

- Thoroughly documented estimates, including key assumptions and uncertainties;

- Clear, routine communication with key stakeholders;

- Internal and external review; and

- Organizational buffers to assure estimate is not influenced by other factors.

WSDOT and OFM should identify an approach that incorporates these practices. WSDOT should use this approach to keep key stakeholders updated on changes to long-term bridge maintenance and preservation cost estimates as well as progress implementing Recommendation One. WSDOT should report its plans to accomplish this to the appropriate Legislative committees by June 30, 2015.

Legislation Required: None Fiscal Impact: None Implementation Date: June 30, 2015

State highway pavement and bridges

-

System overview

WSDOT manages:

- A pavement network of 18,622 lane miles of state highways, and 2,000 lane miles of ramps and special use lanes.

- A bridge network that consists of 3,829 state-owned bridges and structures. This includes structures that range from the SR 520 Bridge to fish culverts.

Other highway assets include:

- 1,100 traffic signal systems

- 48 safety rest areas

- 10 mountain pass highway routes kept open year-round

- Weigh stations

- Guardrails

- Drainage ditches

- Stormwater facilities

-

Maintenance vs. Preservation

Maintenance provides routine activities each year to ensure that highway components will meet operational and service life expectations. Examples of maintenance activities include sealing pavement cracks and patching potholes, making minor bridge repairs, cleaning culverts and drainage ditches, repairing damage caused by motorists or natural events, and controlling snow and ice on highways during winter months.

Preservation is the periodic replacement or restoration of highway system components to renew service life. Examples of preservation work include repaving highways before surface wear and tear lead to subsurface deterioration, painting bridges, replacing bridge deck pavement, and replacing deteriorated culverts. Unlike maintenance, where work is performed on a frequent, recurring cycle, the preservation cycle for an individual asset may be as long as a decade or more.

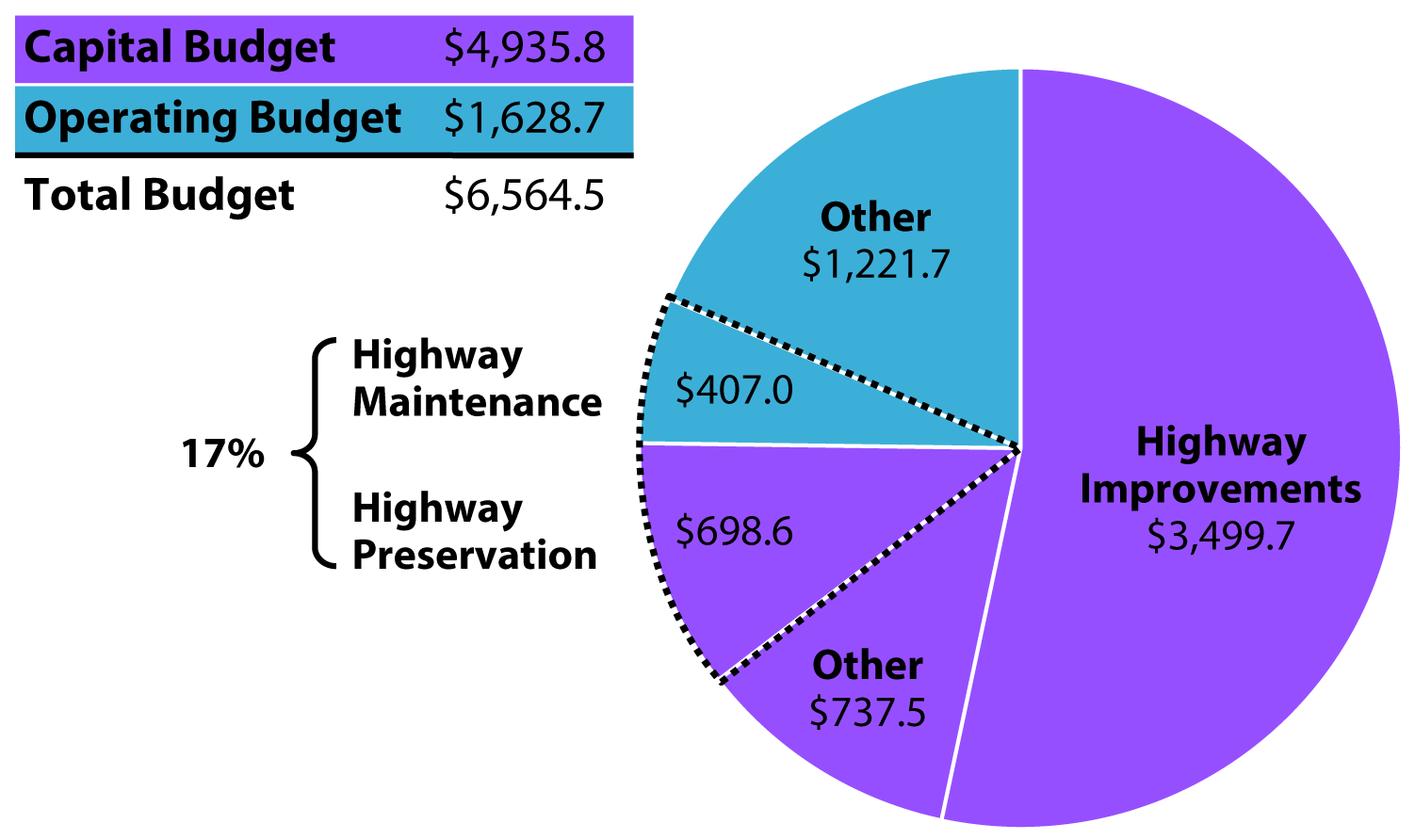

Maintenance and preservation activities accounted for 17 percent of WSDOT’s 2013-15 biennial budget (Exhibit 2 below). Maintenance activities are funded through the operating budget, while preservation work is funded through the capital budget.

Exhibit 2 - Maintenance and preservation are 17 percent of the WSDOT 2013-15 biennial budget (dollars in millions) Source: JLARC staff analysis of 2013-15 WSDOT appropriations.

Source: JLARC staff analysis of 2013-15 WSDOT appropriations. -

Impact of Federal Legislation

WSDOT may need to use certain estimating practices such as life cycle cost analysis and risk assessment in order to receive federal funding.

Federal legislation passed in 2012 called Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century Act (MAP-21) includes new requirements for states that make estimating long-term transportation needs more critical. MAP-21 requires each state to establish performance targets for the National Highway System, and provides sanctions for states that do not achieve the targets. For bridges, the law specifies that no more than 10 percent of the total deck area of National Highway System bridges may be classified as structurally deficient. Other targets, including pavement, may be set by the states under rules that Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) is currently developing.

To describe how each state intends to develop and meet its targets, MAP-21 requires a Transportation Asset Management Plan. Federal guidance requires that these plans establish performance objectives, identify gaps, use life cycle cost and risk management analysis, and develop investment strategies. MAP-21 makes clear reference to the requirement for analysis of life cycle cost and performance, and explicitly ties funding to performance. However, specific requirements will not be known until FHWA formally adopts rules, which is likely to be late 2015 according to FHWA officials.

-

Phase 1 results

Phase 1 of this audit reviewed documentation of the procedures WSDOT follows to estimate maintenance and preservation needs. The Phase 1 report notes that procedures for estimating maintenance and preservation biennial and supplemental budget requests are clearly documented. Procedures for long-term maintenance estimates are also well-documented. However, procedures for estimating long-term preservation needs are not well-documented. Based on these results, Phase 2 focuses primarily on estimating long-term preservation needs. Maintenance is addressed in the context of its role in complementing and supporting preservation activities. Bridge and pavement preservation work account for nearly 70 percent of WSDOT’s 2013-15 highway preservation budget. Phase 2 is focused on these key budget drivers.

Expert consultants address four key questions

JLARC staff contracted with experts in pavement and bridge management to address four key questions.

-

Information accurate?

Is the data that WSDOT uses as the basis of its estimates accurate?

-

Estimating approach follows best practices?

In estimating needs for the next ten years, does WSDOT include:

Expected deterioration that will occur over the next ten years? Most state DOTs use deterioration models to estimate the average number of bridges and pavement miles that will be due for preservation projects in a given time period.

The effectiveness of maintenance and preservation projects that are planned during that timeframe? Effectiveness models predict the conditions after preservation work is completed. Cyclical maintenance actions usually do not improve condition, although they do slow the rate of deterioration. Preservation work and maintenance work that is completed in response to a specific condition, such as a pothole repair, will improve the condition in a manner that will be visible in the next inspection.

-

Minimize life cycle costs?

Does WSDOT base the estimate on managing the bridges and pavement network using life cycle cost analysis? Life cycle cost analysis (LCCA) evaluates the possibility of incurring a smaller expense now for preventive maintenance in order to postpone a much bigger expense later for preservation or replacement projects. This analysis identifies specific alternatives for treating a given asset and determines the stream of costs over time that result from each alternative. For example, a life cycle cost analysis could compare the stream of future costs associated with painting a bridge every 20, 25, or 30 years. By comparing two or more alternatives, a DOT can use life cycle cost analysis to identify the most cost effective alternative.

Life cycle cost analysis can be used at two different levels. Life cycle cost analysis at the project level looks at individual bridge or pavement segments, while analysis at the network level looks at all of the state-owned bridges or pavement miles.

At the … Agencies use LCCA to … Project level Identify the most cost-effective design for a new, replacement, or preservation project Network level Develop maintenance policies and ten-year needs estimates to allocate the correct amount of funding to preservation and maintenance activities to minimize long term costs The distinctions between project and network are important. Work that is appropriate and effective for a specific condition on a given bridge or pavement segment is not necessarily work that the agency can afford to perform statewide. Similarly, strategies that minimize project life cycle costs are not necessarily the same strategies that minimize network life cycle costs.

-

Estimates address risk?

Does WSDOT account for risk in the estimate? There are inevitable uncertainties that a DOT needs to analyze, and develop contingency strategies to address. These include systemic risks, such as changes in the cost and quality of materials and in available revenues, and site specific risks, such as natural or man-made hazards. A truly useful needs estimate evaluates these different scenarios.

estimates are reliable

estimates are reliable

WSDOT uses best practices to estimate current and long-term pavement needs. As a result, the Legislature can consider fiscal and program alternatives based on accurate data and thorough analysis.

-

Information accurate? Yes

The agency’s Washington State Pavement Management System (WSPMS) inventory database contains all of the minimum information requirements and most of the other pavement characteristics identified in industry guidebooks.

To test the reliability of WSDOT’s condition ratings, JLARC’s consultants independently reviewed eight one-mile pavement sections, using the same software and examining the same images that the agency’s surveyors use. The results of the independent review were comparable with WSDOT’s assessment. The consistency between ratings and the quality of WSDOT reference guides indicate that WSDOT has a consistent and repeatable methodology to determine pavement surface condition ratings.

-

Estimating approach follows best practices? Yes

JLARC’s consultants found that WSDOT meets and in many ways exceeds industry standards for estimating long-term (10-year) pavement maintenance and preservation needs. This allows policy makers to understand predicted pavement condition at different funding levels. Below, we review three key questions.

Does WSDOT: WSDOT Status Project the rate that pavement deteriorates? Yes Know the effectiveness of its pavement maintenance and preservation projects? Yes Have the tools to analyze its pavement condition and long-term needs? Yes A more detailed description of WSDOT’s approach to estimating long-term needs is available here.

Consultant Observation: JLARC’s consultants noted that WSDOT does not have documented guidance on (1) how it selects the type of treatment for a given condition, or (2) pavement condition values that would initiate preservation work. They suggest that WSDOT could further improve its pavement management practice by documenting its treatment selection process to guide future decision-makers.

-

Minimize life cycle costs? Yes

JLARC’s consultants determined that WSDOT uses life cycle cost analysis (LCCA) to prioritize pavement investments. Below, we review four key questions.

Does WSDOT: WSDOT Status Use LCCA at the project level? Yes Use LCCA to manage the pavement network? Partial. WSDOT uses life cycle cost analysis to determine its long term funding needs, but may be able to perform work earlier to further extend pavement life. Consider the tradeoffs between earlier, routine maintenance and preservation work later in a pavement segment’s life? No. Few state DOTs do. WSDOT completed a pilot project to do so and has a new system that may allow it to in the future. Estimate its backlog and estimate different fiscal scenarios? Yes A more detailed description of WSDOT’s approach to using life cycle cost analysis is available here.

-

Estimates address risk? Yes

JLARC’s consultants determined that WSDOT’s pavement estimates incorporate risk consistent with best practices. Below, we review three key questions.

Does WSDOT: WSDOT Status Quantify systemic risks, such as changes in material costs and site-specific risks, such as floods or severe storms? Yes Analyze different investment alternatives based on various fiscal scenarios? Yes Consider risk in prioritizing projects and long-term work? Yes A more detailed description of WSDOT’s approach to quantifying risk is available here.

estimates need improvement

estimates need improvement

WSDOT has reliable information on the current condition of state bridges. However, WSDOT’s approach for estimating long-term (10-year) bridge needs is not consistent with best practices. WSDOT’s approach does not allow the agency to systematically assess the impact of alternative funding scenarios on long-term bridge conditions or determine if it is managing the bridge network at the lowest life cycle cost.

-

Information accurate? Yes

JLARC’s consultants found that WSDOT maintains accurate bridge data that can serve as the basis of reliable long-term needs estimates.

To assess the quality of WSDOT’s data, the consultants reviewed the Federal Highway Administration’s (FHWA) 2008-13 Quality Assurance Review reports. These reviews measure the quality of each state’s bridge inspection program and include National Bridge Inspection Standards, data items unique to each state, and the condition of structural elements gathered under American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) guidelines. FHWA found that, with the exception of portions of some types of bridges, the quality of bridge inventory and condition data is excellent.

-

Estimating approach follows best practices? Partial

While WSDOT has excellent data on current bridge conditions, its approach for estimating long-term (10-year) needs is not consistent with best practices. As such, policy makers cannot consider predicted bridge conditions at different funding levels. Based on a review of FHWA and AASHTO guides, JLARC’s consultants identified the following processes that comprise a needs assessment, and they evaluated WSDOT’s ability to complete each process. Below, we review three key questions.

Does WSDOT: WSDOT Status Project the rate that bridges deteriorate? Partial. WSDOT has made progress on developing models for two expensive elements: steel coating systems (which include estimates of paint and steel deterioration rates) and concrete bridge decks. see bridge elements Know the effectiveness of its bridge maintenance and preservation projects? Partial. With a few exceptions, WSDOT has not measured the effectiveness of maintenance or preservation bridge work. Have the tools to analyze its bridge condition and long-term needs? No. WSDOT does not have a system comparable to its pavement management system to manage the state bridge network. A more detailed description of WSDOT’s approach to estimating long-term needs is available here.

-

Minimize life cycle costs? No

JLARC’s consultants determined that WSDOT has not established practices to routinely estimate or minimize bridge life cycle preservation and maintenance costs. Below, we review four key questions.

Does WSDOT: WSDOT Status Use LCCA at the project level? Partial. WSDOT uses industry publications and best practices for standard bridge work that is common across the states. Use LCCA to manage the bridge network? No. WSDOT does not have models or software to help estimate long-term maintenance and preservation costs. Consider the tradeoffs between earlier, routine maintenance and preservation work later in a bridge’s life? Partial. WSDOT completes maintenance work to reduce future costs, but has not determined the optimal allocation between maintenance and preservation. Estimate its backlog and estimate different fiscal scenarios? Partial. Although WSDOT has estimated unfunded work, its estimate was not based on a life cycle cost analysis. Additionally, WSDOT cannot link different investment scenarios to the expected condition of the network. A more detailed description of WSDOT’s approach to using life cycle cost analysis is available here.

-

Estimates address risk? Partial

JLARC’s consultants determined that WSDOT’s estimates partially incorporate risk in estimating bridge maintenance and preservation needs. Below, we review three key questions.

Does WSDOT: WSDOT Status Quantify systemic risks, such as changes in material costs and site-specific risks, such as floods or severe storms? Partial. WSDOT largely accounts for risk in its estimates, but does not consider risk mitigation for man-made hazards, such as collisions, in its long-term estimates. Analyze different investment alternatives based on various fiscal scenarios? No. WSDOT is not required to develop performance constrained maintenance and preservation needs estimates and has not done so. Consider risk in prioritizing projects and long-term work? No. Risk is not integrated into priority setting. A more detailed description of WSDOT’s approach to quantifying risk is available here.

Improving stakeholder confidence in WSDOT’s long-term estimates

WSDOT can improve stakeholder confidence in its long-term pavement and bridge estimates by establishing and communicating a well-documented, thoroughly reviewed estimating process.

-

Guidance on how to improve

Legislators, legislative staff, and other stakeholders need to have confidence in WSDOT’s long-term highway preservation estimates. The Transportation Research Board and others have identified best practices that contribute to a confidence-building forecasting and estimating process. A common theme is to involve parties beyond the agency or project team.

Specific practices include:

- Thoroughly documented estimates, including key assumptions and uncertainties;

- Clear, routine communication with key stakeholders;

- Internal and external review; and

- Organizational buffers to assure estimate is not influenced by other factors.

Documented procedures

In JLARC’s 2014 Phase I Report on Maintenance and Preservation estimates, JLARC found that WSDOT’s process for estimating long-term needs is not as well-documented as it is for the current biennium. The agency did not have specific procedures or a flowchart to document the process for estimating future needs.

Communication with stakeholders

Cost estimates will change over time, for example, as material prices change or new sections are added to the highway system. Also, legislators, legislative staff, and other key stakeholders change over time. So a clear, routine communication is important to keep everyone updated.

WSDOT will need to communicate:

- Key assumptions and uncertainties, such as deterioration rates and material prices; and

- Why estimates have changed.

Exhibit 3 provides an example of the volatility in cost estimates. While there may be legitimate reasons for the wide variation in these estimates, absent clear communication, stakeholders are left with uncertainty about what the correct estimate is.

Exhibit 3 - Clear communication could help explain wide variation of bridge estimates (dollars in millions)Source Steel bridge painting Bridge replacement / rehabilitation Bridge repairs, movable bridges Concrete deck rehabilitation Seismic retrofit 2012 Gray Notebook

(6/2012)$566 $285 $100 $156 $152 “Orange List,” 2013 Session

(1/2013)$490 $272 $100 $92 $105 2013 Gray Notebook

(6/2013)$486 $240 $80 $147 $103 Information Provided by Bridge Office to JLARC (7/2014) $738 Not

requestedNot

requested$123 Not

requested2014 Gray Notebook

(8/2014)$694 Not included Additionally, our consultants indicate it will take some time to fully implement the practices to improve the bridge estimates. It will be important for WSDOT to keep stakeholders fully informed on the status of its progress on bridge estimates.

Internal and external review

Literature recommends two levels of review:

- Internal review from peers, who can identify possible errors, omissions, and clarifications in an estimate; and an

- External review conducted by individuals independent of the originating office to examine the assumptions that form the basis of the estimate and the methods it used to prepare the estimate.

Skepticism concerning the accuracy of a needs estimate or request with a high budget impact is not unique to transportation. The Legislature created the Caseload Forecast Council, which estimates K-12 students, adult and juvenile inmates, and social welfare cases, to address other policy areas. The Council has workgroups that involve its staff, OFM, agency staff, and legislative budget analysts. The Council was created to ensure these other parties have access to the same information that the agency has in developing various caseload forecasts.

Another model is the Transportation Revenue Forecast Council, which WSDOT convenes each quarter with agency, OFM, and legislative staff to estimate transportation revenues.

These models provide opportunities for key stakeholders to review data and raise questions about the methodology and assumptions that underlie estimates. A similar approach to developing maintenance and preservation needs may reduce any uncertainty and skepticism about WSDOT estimates.

Organizational Buffers

JLARC’s 2010 report on Highway Cost Estimating identified protecting cost estimates from outside pressures as a best practice. It noted that clear communication about an estimate’s uncertainty and why it changes is critical to maintaining stakeholder trust and building confidence.

As noted above, communication is critical to long-term estimates as well. Unlike individual projects, where stakeholders may seek to accelerate design and construction, the primary stakeholder concern with long-term preservation estimates is that WSDOT may overestimate needs, and Legislative staff lack the time and expertise to fully analyze and vet WSDOT estimates.

Clearly documenting changes in estimates and assumptions, working with stakeholders to communicate the reasons for these changes, and allowing for review, can help protect long-term estimates from undue influence.

Side by side comparison of bridge and pavement estimating practices

Link to consultants’ detailed technical report

Agency Responses:

Contact

Authors of this Study

Mark Fleming, Research Analyst, 360-786-5181

Eric Thomas, Research Analyst, 360-786-5182

Valerie Whitener, Audit Coordinator

Keenan Konopaski, Legislative Auditor

Joint Legislative Audit and Review Committee

Eastside Plaza Building #4, 2nd Floor

1300 Quince Street SE

PO Box 40910

Olympia, WA 98504-0910

Phone: 360-786-5171

FAX: 360-786-5180

Email: JLARC@leg.wa.gov

Audit Authority

The Joint Legislative Audit and Review Committee (JLARC) works to make state government operations more efficient and effective. The Committee is comprised of an equal number of House members and Senators, Democrats and Republicans.

JLARC’s non-partisan staff auditors, under the direction of the Legislative Auditor, conduct performance audits, program evaluations, sunset reviews, and other analyses assigned by the Legislature and the Committee.

The statutory authority for JLARC, established in Chapter 44.28 RCW, requires the Legislative Auditor to ensure that JLARC studies are conducted in accordance with Generally Accepted Government Auditing Standards, as applicable to the scope of the audit. This study was conducted in accordance with those applicable standards. Those standards require auditors to plan and perform audits to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for findings and conclusions based on the audit objectives. The evidence obtained for this JLARC report provides a reasonable basis for the enclosed findings and conclusions, and any exceptions to the application of audit standards have been explicitly disclosed in the body of this report.

Committee Action to Distribute Report

On January 7, 2015 this report was approved for distribution by the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Committee.

Action to distribute this report does not imply the Committee agrees or disagrees with Legislative Auditor recommendations.

JLARC Members on Publication Date

Senators

Randi Becker

John Braun, Vice Chair

Annette Cleveland

David Frockt

Janéa Holmquist Newbry

Jeanne Kohl-Welles, Secretary

Mark Mullet

Ann Rivers

Representatives

Tami Green

Kathy Haigh

Larry Haler

Ed Orcutt

Gerry Pollet

Derek Stanford, Chair

J.T. Wilcox

Hans Zeiger, Asst. Secretary

Scope & Objectives

Why a JLARC Study of How WSDOT Assesses Highway Preservation and Maintenance Needs?

The Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) is responsible for maintaining and preserving a statewide highway system of more than 20,000 lane miles of pavement, over 3,400 bridges and structures, and numerous other supporting assets such as signal systems and drainage ditches.

The 2013-15 Transportation Budget (ESSB 5024) directs the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Committee (JLARC) to conduct a review of the methods and systems used by WSDOT to develop asset condition and maintenance service level needs and subsequent funding requests for highway preservation and maintenance programs.

“Maintenance” and “preservation” represent the activities needed to keep the highway system functioning. Maintenance begins when a highway asset such as a pavement surface, is placed in service and includes activities that keep the asset in service over its lifetime. For example, routine pavement maintenance includes filling potholes, sealing cracks, and restoring traffic markings. Crews from the six WSDOT regional offices perform these routine activities. The 2013- 15 Transportation Budget appropriates $407 million to WSDOT for highway maintenance.

In contrast, preservation occurs at the end of the asset’s service life when, even with the best routine maintenance, the asset must be replaced. For example, asphalt pavement typically has a service life of 15 years after which it can no longer provide a smooth and safe driving surface and prevent failure of the underlying substructure. A preservation project would replace the asphalt on a stretch of highway. Preservation work is performed by private contractors. The 2013-15 Transportation Budget appropriates $699 million to WSDOT for highway preservation.

WSDOT is responsible for identifying highway maintenance and preservation needs. WSDOT also estimates the costs of meeting these needs.

Study Scope

The Legislature directed JLARC to conduct this review in two parts. Phase 1 will provide an overview of the methods and systems used by WSDOT to estimate highway maintenance and preservation needs and costs. Phase 2 will examine whether the methods and systems WSDOT uses for estimating highway preservation and maintenance needs and costs are consistent with industry practices and other appropriate standards.

Study Objectives

Phase 1 of this review will address the following questions:

Phase 2 will address the remaining questions of the mandate:

Timeframe for the Study

Staff will present the Phase 1 report at the January 2014 JLARC meeting. Staff will present the Phase 2 report at the December 2014 JLARC meeting.