JLARC Final Report: State Recreation and Habitat Lands

Report 15-1, July 2015

Legislative Auditor’s Conclusion:

Legislature Would Benefit From Additional Information About Detailed Outcomes and Future Costs of Recreation and Habitat Lands When Considering Funding Requests

- Results what we learned

- Report details

- Response from agencies

- More about the study

- View/Print entire report

The Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission (State Parks), the Department of Natural Resources (DNR), and the Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW) purchase and manage lands intended to provide recreation and preserve habitat. The Legislature appropriates funds to acquire these lands and requested a study of acquisitions, costs, and use of economic measures.

Reports do not link acquisitions to detailed outcomes or future costs

Five agencies currently report information about recreation and habitat land acquisitions to the Legislature: State Parks, DNR, WDFW, the Recreation and Conservation Office (RCO), and the Office of Financial Management (OFM).

- Key information about acquisitions and funding is spread across several reports and websites.

- The extent of information reported about detailed outcomes varies by report and by agency. For example, a report may indicate that a project will provide general outcomes such as low-impact recreation or habitat protection. However, it may not specify detailed outcomes such as plans for trail development or future habitat restoration needs.

- The Legislature also lacks reliable information about future costs.

The Legislative Auditor recommends that the five agencies develop a single, easily-accessible source for information about proposed recreation and habitat land acquisitions, including detailed outcomes and future costs. The agencies can build on work they already do to accomplish this. The agencies indicated they partially concur with the Legislative Auditor's recommendation.

Inventory of recreation and habitat land acquisitions

Between fiscal years 2004 and 2013, State Parks, DNR, and WDFW:

- Increased their habitat and recreation land base by 120,470 acres (11%);

- Spent $413 million to acquire new lands; and

- Spent an estimated $558 million to manage all of their recreation and habitat lands, including recent acquisitions.

Agencies have considerable information about habitat and recreation land transactions and expenditures. Data gaps and the use of multiple systems hinder analysis and reporting.

Formal analysis of economic costs and benefits not routinely performed or required

State law does not require agencies to analyze the economic costs and benefits of properties before or after they acquire recreation or habitat land. State Parks, DNR, and WDFW do not regularly conduct benefit-cost analysis or other types of formal economic analysis for acquisitions. Instead, the agencies often cite national studies. While these studies may be valid, it is important to recognize that results may not be directly applicable to all lands owned by State Parks, DNR, or WDFW. There are key questions policy makers should ask to understand the results of an economic analysis.

Legislative Auditor Recommends

Five agencies currently report information about recreation and habitat land acquisitions to the Legislature:

- Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission (State Parks)

- Department of Natural Resources (DNR)

- Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW)

- Recreation and Conservation Office (RCO)

- Office of Financial Management (OFM)

The agencies provide detailed information about proposed acquisitions and funding requests, but it is spread across several reports and web sites. While general outcome information may be provided, the extent of information about detailed outcomes varies by agency and project. The Legislature also lacks reliable information about future costs.

The Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission, the Department of Natural Resources, the Department of Fish and Wildlife, the Recreation and Conservation Office, and the Office of Financial Management should develop a single, easily-accessible source for information about proposed recreation and habitat land acquisitions, including detailed outcomes and future costs.

The type of information provided by the agencies should be consistent and include all of the following:

Provide details about acquisition and funding

- Provide details about the properties proposed for acquisition, including location, acreage, and current use.

- Identify the estimated acquisition cost and fund source(s).

- Include all proposed acquisitions, regardless of fund source(s).

Link acquisitions to plans and detailed outcomes

- Explain how the acquisition relates to the agency’s plans for an entire management unit (i.e., state park, wildlife area, or natural area).

- Clearly identify the detailed outcomes for the property and entire management unit such as specific development plans, service improvements, staffing levels, or habitat restoration needs.

- Clearly describe agency progress toward achieving the detailed outcomes and how the acquisition helps achieve those outcomes.

Identify future costs to achieve and maintain detailed outcomes

- Estimate future capital, operating, and maintenance costs for the entire management unit, including the costs to achieve the detailed outcomes.

- Explain how the proposed acquisition affects those estimated costs.

State Parks, DNR, WDFW, RCO, and OFM should develop a single, easily-accessible source for information about acquisitions, detailed outcomes, and costs. In undertaking this effort, the agencies can build on work they are already doing. This work includes Lands Group reports, budget documents, land management plans, and grant program applications. These agencies also should establish guidelines and reporting protocols so that they are providing consistent information to the Legislature.

OFM should develop guidelines that standardize the cost estimates. Guidelines should address, at minimum, the number of biennia that estimates must cover and the types of expenses to be included. OFM should develop a process to reconcile estimated costs with actual expenditures. OFM and the agencies should use that reconciliation to inform future cost estimates and budget requests.

State Parks, DNR, WDFW, RCO, and OFM should report to the Legislature by January 1, 2016 with a proposal that outlines how the recommendation will be implemented and estimates of any associated costs.

| Legislation Required: | No |

| Fiscal Impact: | JLARC staff assume the proposal can be completed within existing resources. Implementation of the proposal may require other resources. |

| Implementation Date: | Proposal due January 1, 2016 |

| Agency Reponse: | Partially concur - see link here |

Reports do not link acquisitions to detailed outcomes or future costs

Agencies describe proposed acquisitions and funding details in multiple reports to the Legislature. Some reports also identify general outcomes, but lack details. For example, an agency may indicate that a project will provide low-impact recreation but not specify plans for trail development. Likewise, an agency may indicate that a project will protect habitat for a species, but not specify future restoration needs. Some reports include limited information about future costs. Agencies need to consistently calculate and report future operating and capital costs.

-

Complete information would inform decisions

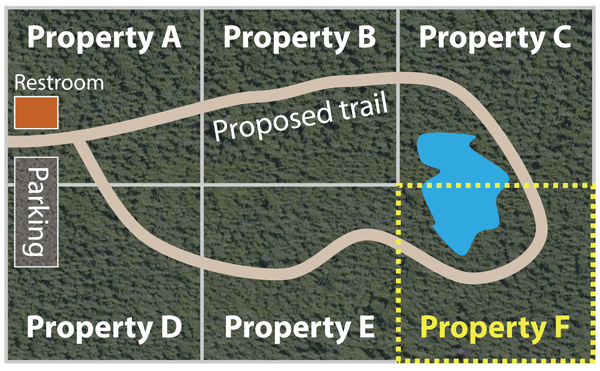

A hypothetical example illustrates the need for complete information.

Exhibit 1 - Complete information about detailed outcomes and future costs could inform a legislative decision about acquiring Property F Source: JLARC staff example.

Source: JLARC staff example.An agency may have long-term plans to acquire and develop six adjoining properties. In the next legislative session, the agency intends to ask the Legislature for funding to acquire 1 of the 6 properties. This is illustrated as Property F in Exhibit 1.

The agency may have plans or other documents that explain its intent to build a trail through the properties once it has acquired all 6, and to install a restroom and a parking area at one end. However, while these long-term plans and detailed outcomes may inform the agency’s decisions and potential grant funding evaluations, they will not accompany the budget request for Property F. Instead, reports to the Legislature are more likely to indicate that the property may be used for low-impact recreation. The Legislature also may not receive information about how many of the other properties the agency already owns and how many more it intends to acquire. Nor will the Legislature receive an estimate of the future costs to develop and maintain the whole area.

The agency may accurately report to OFM, who would then report to the Legislature, that it estimates zero additional operations and maintenance costs for the one property during the next biennium or two because the agency does not plan to develop the area until it has all the properties. In the long-run, however, the operation, maintenance, and development costs for the entire area may be substantial.

-

Acquisition details in many reports to Legislature

The Legislature receives reports that provide details (e.g., location, purchase price) about proposed land acquisitions, funding for those acquisitions, and whether previously funded acquisitions were purchased. In the past, the Legislature also has received reports that estimate two biennia of operations and maintenance costs for planned acquisitions. The extent of information about outcomes and future costs varies by report.

Exhibit 2 - Information received by LegislatureProvides acquisition and funding details Links acquisitions to plans and outcomes Identifies future costs Lands Group reports Yes Partial Partial Trust Land Transfer list Yes Partial No RCO project lists and grant reports Yes No No OFM operating cost estimate reports Partial No Partial Source: JLARC staff analysis of reports.Lands Group Reports

The Legislature established the Habitat and Recreation Lands Coordinating Group (Lands Group) in 2007 to improve the coordination and transparency of state agency land acquisitions.

The biennial forecast provides information about proposed acquisitions.

- The forecast provides details such as project descriptions, acquisition costs, and funding details.

- The forecast identifies intended use and the related statewide and agency strategic plans for most acquisitions. For many acquisitions, the forecast does not clearly explain how acquisitions fit within an agency’s plans for an entire management unit (i.e., state park, wildlife area, or natural area).

- The report does not currently identify future costs.

The monitoring report compares proposed and actual acquisitions. The report provides details such as project descriptions, acreage, acquisition costs, and funding details.

- The report does not include detailed outcomes. It does offer maps, some of which show the location of the acquisition within the entire management unit. It also identifies whether planned acquisitions were ultimately acquired.

- The report identifies future payments made to counties to compensate for the loss of property taxes (payments in lieu of taxes or PILT). Estimates of operations and maintenance costs are provided for some acquisitions.

The Lands Group also holds a biennial forum , which is a public meeting for discussing potential acquisitions and disposals. Forum materials include the same information as the forecast and monitoring reports. Estimates of operations and maintenance costs are provided for some acquisitions.

State Parks, DNR, and WDFW provide the information for both Lands Group reports, which are published by the Recreation and Conservation Office.

Trust Land Transfer List

State trust lands generate revenue for public school construction. DNR’s Trust Land Transfer program moves lands from trust status to DNR’s natural areas program or other public agencies for recreation or habitat purposes.

The Legislature receives a list of proposed transfers:

- The list provides detailed information on the properties to be transferred (e.g., acreage, location, characteristics), the entity receiving the property, and the estimated property value.

- The list provides limited information about the proposed use but does not link that use to detailed outcomes. For example, it does not specify how a property transferred to State Parks relates to the services and development at an adjoining park.

- The list does not identify future costs.

RCO Project Lists and Grant Reports

The Recreation and Conservation Office (RCO) administers grant programs that fund acquisitions made by State Parks, DNR, and WDFW. RCO sends a ranked list of projects and a more detailed “Blue Report” to the Legislature each biennium to support its funding request.

- Project lists and the report offer acquisition information such as the project name, amount requested, location, and a brief summary of the project.

- Neither the list nor the report explain how the acquisitions relate to the agency’s plans or detailed outcomes for an entire management unit (i.e., state park, wildlife area, or natural area).

- Neither the list nor the report identifies future costs.

RCO posts additional information about projects on its website.

OFM Operating Cost Estimate Reports

By law, when an agency requests funds to acquire recreation or habitat land, it must either (1) provide an estimate of costs for two biennia following acquisition or (2) assert that there will be no future operations and maintenance costs.

OFM has not reported estimates to the Legislature since Fiscal Year 2010.

- Reports until Fiscal Year 2010 included project names and operating cost estimates, but only for acquisitions proposed through RCO grants or the Trust Land Transfer program.

- Reports did not link the acquisitions to agency plans or outcomes.

- Reports had limited information about future operations and maintenance costs of the acquisition. Many estimates reflected the cost only of the acquired property and did not include the future costs for entire management units (i.e., state park, wildlife area, or natural area).

-

Outcome information varies in detail

Agencies develop documents that aid in their decision making. These documents describe the general outcomes for entire management units (i.e., state parks, wildlife areas, and natural areas). However, they may not include detailed outcomes such as specific development plans or habitat restoration needs. Some documents show how future acquisitions relate to larger plans. The extent of information varies by report and by agency. Agencies are not currently required to submit these plans to the Legislature.

Exhibit 3 - Extent of information about outcomes varies by report and by agencyProvides acquisition and funding details Links acquisitions to plans and outcomes Identifies future costs State Parks CAMP plans* No Partial No New management efforts No No Partial DNR Natural Heritage Program No Partial No Natural area management plans* No Partial No WDFW Wildlife area plans No No No Lands 20/20 plan, policies, process, and applications Yes Yes No RCO Grant evaluation processes Yes Partial No * Agencies have not completed plans for all state parks or natural areas.Source: JLARC staff analysis of reports.

State Parks

State Parks develops Classification and Management Planning documents (CAMP plans) for specific parks or park areas. Park areas comprise one or more parks or historical landmarks.

- CAMP plans identify long-term boundaries for parks within which the agency may acquire land. The plans do not offer an acquisition strategy with details of proposed acquisitions. Agency staff identify the details when they propose acquisitions.

- CAMP plans offer information about general and detailed outcomes, including goals, management approaches, and land classifications based on purpose and intensity of use (e.g., recreation use, heritage area, natural area). This information is linked to long-term boundaries, not specific acquisitions.

- CAMP plans do not identify future costs.

State Parks has initiated two new management efforts—one for day-to-day maintenance and one for the condition of facilities.

- Neither effort addresses acquisitions, nor do they presently link to CAMP plans.

- While neither effort is intended to forecast additional future costs from acquisition or development, the information could be used to assist with estimates.

- Standardizing routine maintenance activities across the system will help determine staffing levels based on each park’s current features (e.g., campgrounds, trails).

- A map-based inventory that includes the location and condition of all built facilities will guide the agency’s planning and budgeting for deferred maintenance.

Natural Resources (DNR)

DNR’s Natural Heritage Program provides data about rare species and ecosystems that is used to help establish the boundaries for natural areas. Natural areas include natural area preserves and natural resources conservation areas. Both are intended to preserve habitat and protect plants or animals, and also may provide passive recreation.

- Information from the program is used to identify the area within which DNR may acquire land based on selection criteria. The program does not offer an acquisition strategy with details of proposed acquisitions.

- The program identifies selection criteria, including the species to be protected, condition of the habitat and natural processes, surrounding landscape, and known management issues. This information is linked to long-term boundaries, not specific acquisitions.

- Estimated future costs are not among the criteria.

DNR has completed site-specific management plans for 18 of its 91 natural areas.

- Plans do not contain descriptions of specific acquisitions.

- Plans include general outcome information such as the long-term boundary and management goals. Plans also contain information on the site history and natural resources (e.g., soil type, topography, species present).

- Plans do not identify the future costs to achieve long-term boundaries or management goals.

Fish and Wildlife (WDFW)

WDFW has a management plan for each wildlife area. Wildlife areas are intended to preserve habitat for fish and wildlife. Many also provide recreation opportunities.

The plans are primarily retrospective. They recount events and activities but incorporate little future planning.

- Management plans do not contain descriptions of future acquisitions.

- Management plans identify a limited set of site conditions and general outcomes but lack detailed strategies for achieving them. Acquisitions are not linked to these outcomes.

- Management plans do not contain estimated future costs.

The agency has a new planning process that is intended to identify funding constraints and needs, and then prioritize land management activities within the funding available. WDFW is testing the process at the Swanson Lakes and Klickitat Wildlife Areas and plans to initiate two other plans by the end of Fiscal Year 2015.

WDFW acquisitions are informed by plans, policies, and procedures collectively referred to as “Lands 20/20.”

- The Lands 20/20 plan, policies, and procedures provide guidelines for selecting acquisitions. These are high-level planning documents. Agency staff identify details about specific lands when they are proposed for acquisition.

- Lands 20/20 identifies acquisition selection criteria such as benefits to fish and wildlife, benefits to the public, and operational considerations. Acquisitions are linked to detailed outcomes when they are proposed.

- Lands 20/20 does not contain estimated future costs. Acquisition proposals are supposed to include estimated operations and maintenance costs and long-term management responsibilities, but the proposals discuss costs only in very general terms.

Recreation and Conservation Office (RCO)

Recreation and Conservation Office (RCO) grant programs require acquisition details and general outcomes for project proposals. A project can include more than one acquisition.

- Grant applications must include acquisition details such as acreage, location, and estimated acquisition cost.

- For most grant programs, applications must explain general outcomes such as how the project relates to existing lands or agency plans. This is not required for individual acquisitions. Grant program requirements vary, with some requesting more limited information.

- Grant programs do not ask agencies to identify future costs.

-

Future costs largely unknown

Current estimates are incomplete or have limited usefulness

Current agency reports provide limited estimates of the future costs associated with individual acquisitions or with entire management units such as parks and wildlife areas.

The current approaches used to estimate costs limit their usefulness:

- Neither OFM nor the Lands Group provide a standard methodology for making operations and maintenance cost estimates. Without a standard, the approaches vary across agencies and across biennia such that comparison is not valid.

- Some acquisitions are part of a phased approach, and the operations and maintenance costs will not increase until all phases are complete. For example, if an acquisition is one of many that are needed for a trail, it is possible that operations and maintenance costs would not increase until after the trail is developed.

- State Parks, DNR, and WDFW do not maintain the operations and maintenance estimates in their databases and do not incorporate estimates into other planning documents.

- Estimates cannot be compared to actual expenses because agencies currently make estimates for individual acquisitions, but track actual expenses for entire management units or programs. Thus, there is no way to determine later whether the estimates were accurate.

Acreage alone does not predict operating costs

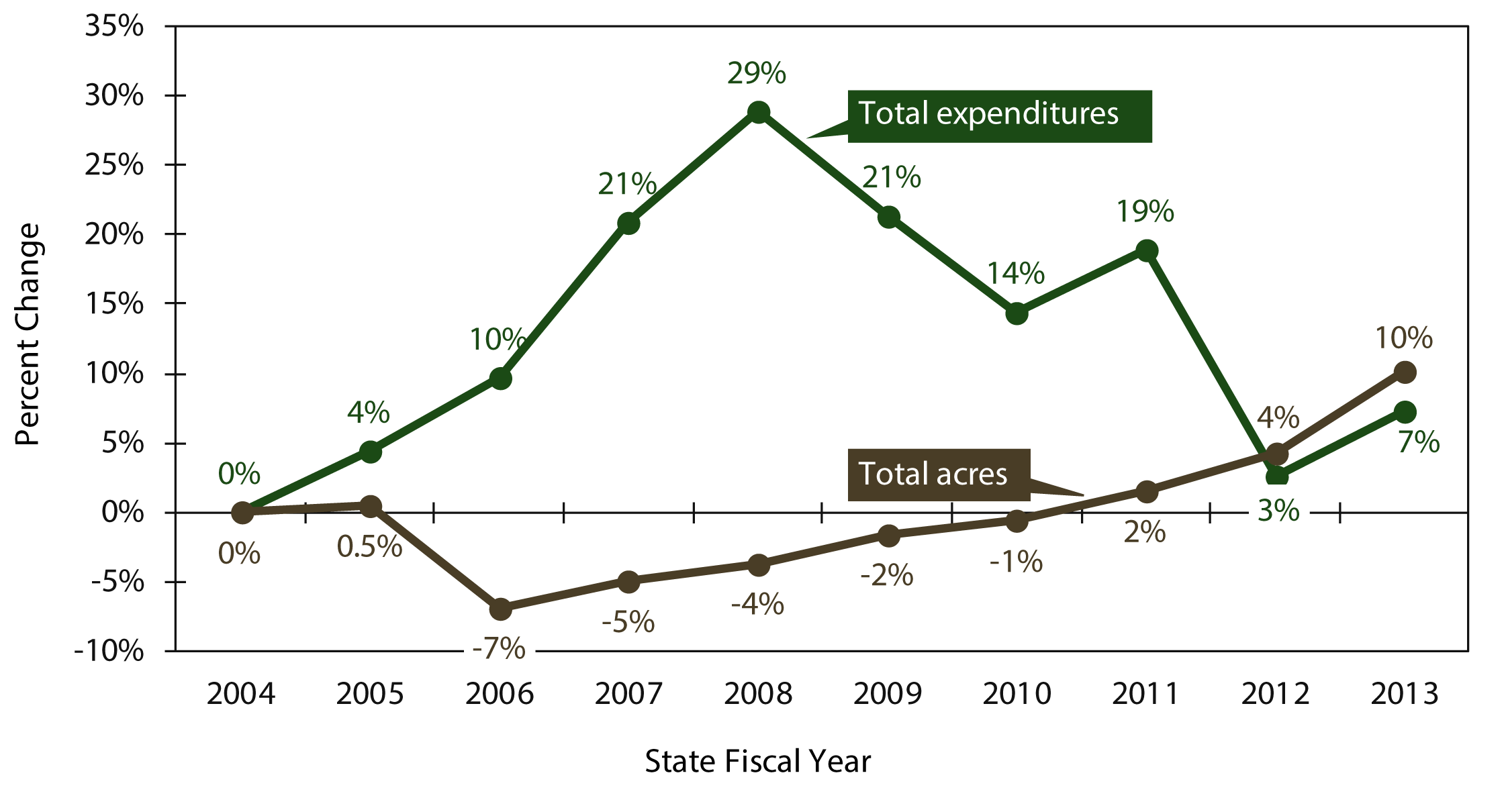

Change in the land base is not a good predictor of operations and maintenance costs. Over 10 years, the total estimated amount the agencies spent to manage lands did not increase or decrease directly with changes in acreage (Exhibit 4). This was true for total expenses by all three agencies and for each agency individually.

The largest recreation and habitat sites were not necessarily the most expensive to manage. For example, Fort Worden State Park had the highest management costs of all state parks in Fiscal Year 2013 but ranked 60th in terms of acreage. Likewise, the Sunnyside-Snake River Wildlife Area had the highest management cost of all wildlife areas in Fiscal Year 2013 but ranked 12th in terms of acreage.

A statewide average cost per acre cannot predict future costs for a particular site because land management costs varied widely. For example, the average annual cost to manage individual parks ranged from $14 per acre to $16,500 per acre. The average annual cost to manage wildlife areas ranged from $3 per acre to $100 per acre.

Exhibit 4 - Estimated operating expenditures and acreage by year, compared to FY 2004 baseline (expenditure data adjusted for inflation) Source: JLARC staff analysis of data from DNR, WDFW, State Parks, LEAP, and the State Treasurer. Fiscal Year 2004 through Fiscal Year 2013.

Source: JLARC staff analysis of data from DNR, WDFW, State Parks, LEAP, and the State Treasurer. Fiscal Year 2004 through Fiscal Year 2013.Intended use does not predict future costs

State Parks, DNR, and WDFW state how they intend to use a property before acquiring it, but the intended use does not appear to be a good predictor of future costs.

- WDFW and DNR reported that all of the properties they acquired met the intended use.

- State Parks reported that 120 newly-acquired properties met intended use. Fourteen have not yet met intended use. The agency estimated that currently planned development at six of the 14 properties would cost approximately $65 million for restrooms, trails, and parking. The remaining eight properties are intended for cabins, yurts, trails, parking, or low-impact recreation.

Meeting intended use does not mean that a property has no future costs. Many properties will require ongoing management. Some will require additional investments that may increase future expenses for operations or maintenance. For example, an agency may use a property for habitat, but still request future funding to improve its condition. Likewise, a property may be used for recreation, but the agency may request funding for designated parking or other facilities.

Summary of Legislative Auditor Recommendation

When making funding decisions about proposed recreation and habitat land acquisitions, the Legislature would benefit from additional information about the detailed outcomes and future costs for the property and the entire management unit.

State Parks, DNR, WDFW, RCO, and OFM should develop a single, easily-accessible source for information about proposed habitat and recreation land acquisitions, including detailed outcomes and future costs.

Ten-year inventory of state habitat and recreation lands

The Legislature directed JLARC staff to inventory the agencies’ recreation and habitat land acquisitions for the past 10 years. State Parks, DNR, and WDFW provided JLARC staff with information about their recreation and habitat acquisitions and disposals, as well as their land management expenses, for fiscal years 2004 through 2013. However, the information was difficult to analyze and report because of how it is collected and stored by the agencies.

-

Acreage increased 11% over 10 years

Net increase was 120,470 acres

From Fiscal Year 2004 through 2013, State Parks, DNR, and WDFW acquired 241,231 acres and disposed of 120,761 acres in parks, natural areas, wildlife areas, and water access sites (Exhibit 5). The net increase of these recreation and habitat lands was 120,470 acres.

The inventory reflects recreation and habitat lands owned or managed by the agencies. As such, it includes properties that the agencies acquired or disposed of through leases, exchanges, or donations in addition to new purchases.

Exhibit 5 - Agencies acquired 241,231 acres and disposed of 120,761 acresAgency Starting Acres 6/30/03 Acres Acquired Acres Disposed Net Change Ending Acres 6/30/13 Parks 133,697 6,114 -2,651 3,463 137,160 DNR 116,572 34,535 0 34,535 151,107 WDFW 861,007 200,582 -118,110 82,472 943,478 Grand Total 1,111,276 241,231 -120,761 120,470 1,231,745 Source: JLARC staff analysis of data provided by State Parks, DNR, and WDFW, Fiscal Year 2004 through Fiscal Year 2013.Net change varies by county

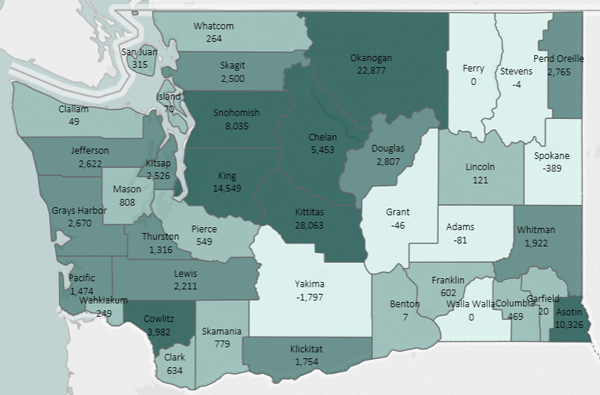

The agencies acquired or disposed of land in 37 of the state’s 39 counties.

However, 77% of the net increase took place in 7 counties.

- DNR’s acquisitions for the Mount Si, West Tiger Mountain, and Morning Star natural areas drove net increases in King and Snohomish counties.

- WDFW’s transactions for wildlife areas drove net increases in Kittitas, Okanogan, Asotin, Chelan, and Cowlitz counties.

Exhibit 6 shows the net change by county. Click to view an interactive map with additional details by county.

Exhibit 6 - Some counties have greater net changes in recreation and habitat land acreage than othersSource: JLARC staff analysis of data provided by State Parks, DNR, and WDFW, Fiscal Year 2004 through Fiscal Year 2013.Exhibit 7 - Acquisition purpose varied by agency Source: JLARC staff analysis of data provided by State Parks, DNR, and WDFW, Fiscal Year 2004 through Fiscal Year 2013.

Source: JLARC staff analysis of data provided by State Parks, DNR, and WDFW, Fiscal Year 2004 through Fiscal Year 2013.Properties have many purposes

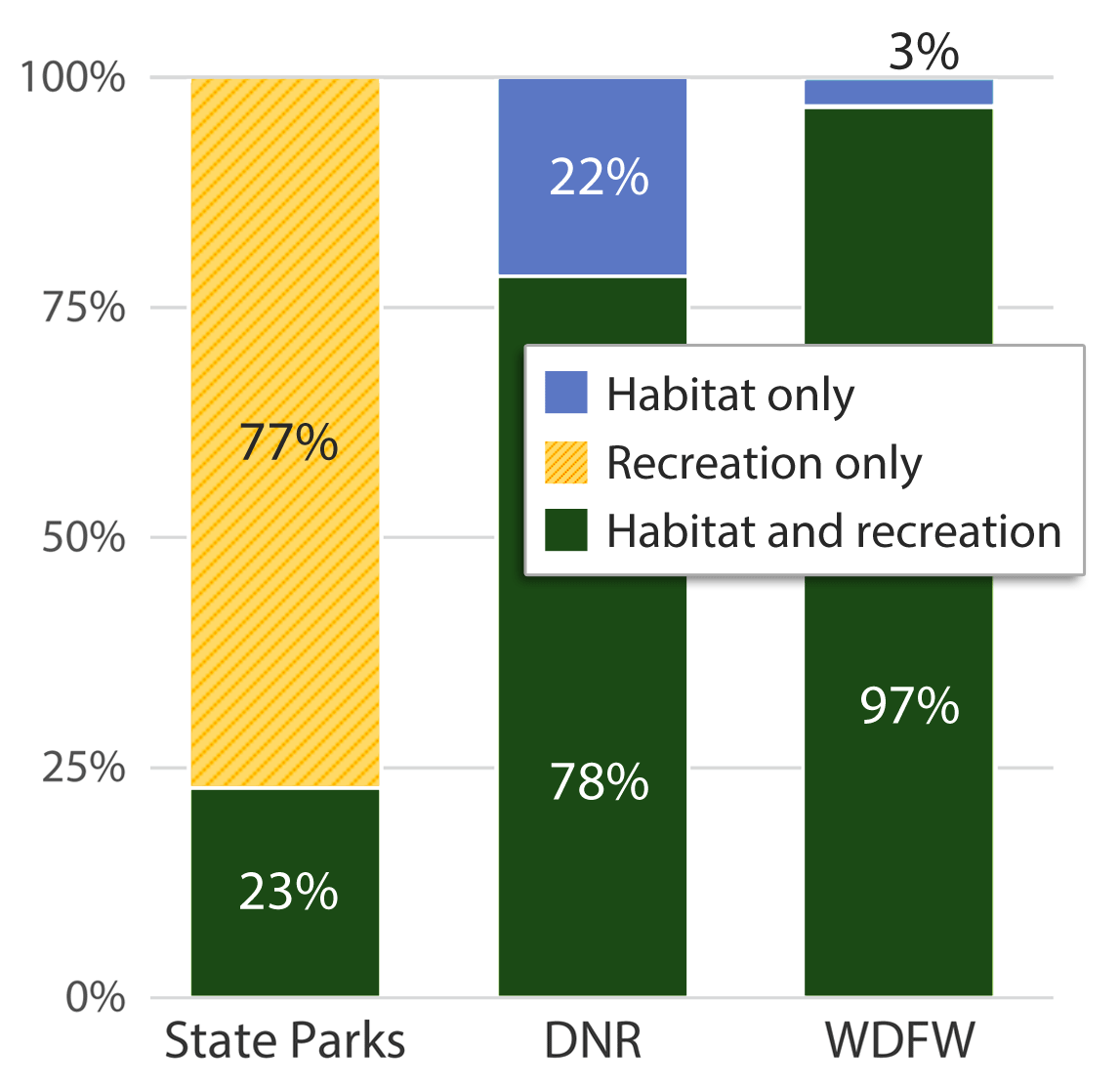

State Parks, DNR, and WDFW have different purposes for the lands they acquired (Exhibit 7).

State Parks reports that it acquired 77% of its acreage for recreation, including picnicking, trails, or water access. It also acquired properties that are intended to provide both recreation and habitat.

DNR acquired habitat-only properties for its natural area preserves, which have limited public access and are meant to protect rare species and ecosystems. For its natural resources conservation areas, it acquired dual-purpose properties, which often feature trails or low-impact recreation in addition to habitat.

WDFW reports that 97% of the acres acquired serve both recreation and habitat purposes. Most of these newly acquired lands provide habitat and hunting, and some also offer wildlife viewing. Acres purchased for WDFW’s water access sites provide recreation only.

-

Agencies spent $413 million to acquire land

Agencies used state, federal, and other funding

State Parks, DNR, and WDFW spent $413 million in state, federal, and other funds to acquire land from Fiscal Year 2004 through Fiscal Year 2013. This amount reflects the purchase price and excludes administrative and incidental costs (Exhibit 8).

WDFW used the most federal funding, primarily from U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service grant programs that align with WDFW’s mission.

Exhibit 8 - $413 million spent from state, federal, and other sources to acquire recreation and habitat land. 82 % was state funds (dollars in millions not adjusted for inflation)Agency State Funds Federal Funds Private, Local or Other Total Spent Parks $59.0 $10.9 $4.3 $74.2 DNR $193.7 $7.1 $0.2 $201.0 WDFW $85.5 $42.6 $9.8 $138.0 Total $338.2 $60.6 $14.3 $413.2 Percent of Total 82% 15% 3% 100% Source: JLARC staff analysis of data provided by State Parks, DNR, and WDFW, Fiscal Year 2004 through Fiscal Year 2013.

The totals may not match the sum of individual parts due to rounding.

95% of state funding for acquisitions is from Trust Land Transfers and RCO grants

The agencies spent $338 million of state funds to acquire property (Exhibit 9).

Most of this funding came from two sources:

- DNR’s Trust Land Transfer program allows DNR to move lands from the trust to a public agency for recreation or habitat purposes. The trust, which generates revenue for public school construction, is compensated through a legislative appropriation. The state spent $181 million to transfer 30,490 acres to DNR’s natural areas program, State Parks, and WDFW.

- RCO’s grant programs provide funds to the agencies for specific recreation and habitat acquisitions. The agencies spent $141 million in RCO grants. Most of the grants that the agencies receive are through the Washington Wildlife and Recreation Program (WWRP).

Other state funds include the Parkland Acquisition Account, direct appropriations, and the migratory bird program.

Exhibit 9 - Most state acquisition funding is from Trust Land Transfers and RCO grants (dollars in millions not adjusted for inflation)Agency Trust Land Transfers RCO Grants Other State Funding Total Spent Parks $19.9 $32.7 $6.4 $59.0 DNR $145.7 $47.9 $0.0 $193.7 WDFW $15.6 $60.7 $9.2 $85.5 Total $181.3 $141.3 $15.6 $338.2 Percent of Total 53% 42% 5% 100% Source: JLARC staff analysis of State Parks, DNR, and WDFW data, Fiscal Year 2004 through Fiscal Year 2013.

The totals may not match the sum of individual parts due to rounding.

-

Land management expenses and fund sources vary

Spending reflects appropriations and management

From Fiscal Year 2004 through Fiscal Year 2013, State Parks, DNR, and WDFW spent an estimated $558 million to manage all of their recreation and habitat lands (Exhibit 10).

This estimate includes:

- Expenses such as staff, vehicles, weed control, tree trimming, and supplies.

- Payments made to counties to compensate for the loss of property taxes (payments in lieu of taxes or PILT). The State Treasurer distributes PILT payments to counties for DNR properties.

Exhibit 10 - Ten-year spending estimate by agency and fund source to manage recreation and habitat lands (dollars in millions not adjusted for inflation)Agency State General Fund Other State Funds Federal Funds Private, Local or other Total Spent Parks $221.0 $222.4 $0.4 $1.2 $445.0 DNR $14.0 $4.6 $1.0 $0.5 $20.1 WDFW $17.5 $28.8 $42.0 $4.9 $93.3 Total $252.5 $255.8 $43.4 $6.6 $558.3 Source: JLARC staff analysis of data from DNR, WDFW, State Parks, LEAP, and the State Treasurer. Fiscal Year 2004 through Fiscal Year 2013. Includes payments in lieu of taxes (PILT) of $7.4 million for DNR lands and $7.6 million for WDFW lands.

The totals may not match the sum of individual parts due to rounding.

Land management costs not identified by acquisition

The agencies do not track operating or maintenance expenses for specific acquisitions. Rather, the land management expenses for newly acquired properties are accounted for as part of a larger management unit, such as a park or wildlife area. The estimated annual expenditures for management units vary widely. Because of this accounting approach, JLARC staff determined that it was not possible to accurately identify operating or maintenance costs for only new acquisitions.

Agency spending over ten years

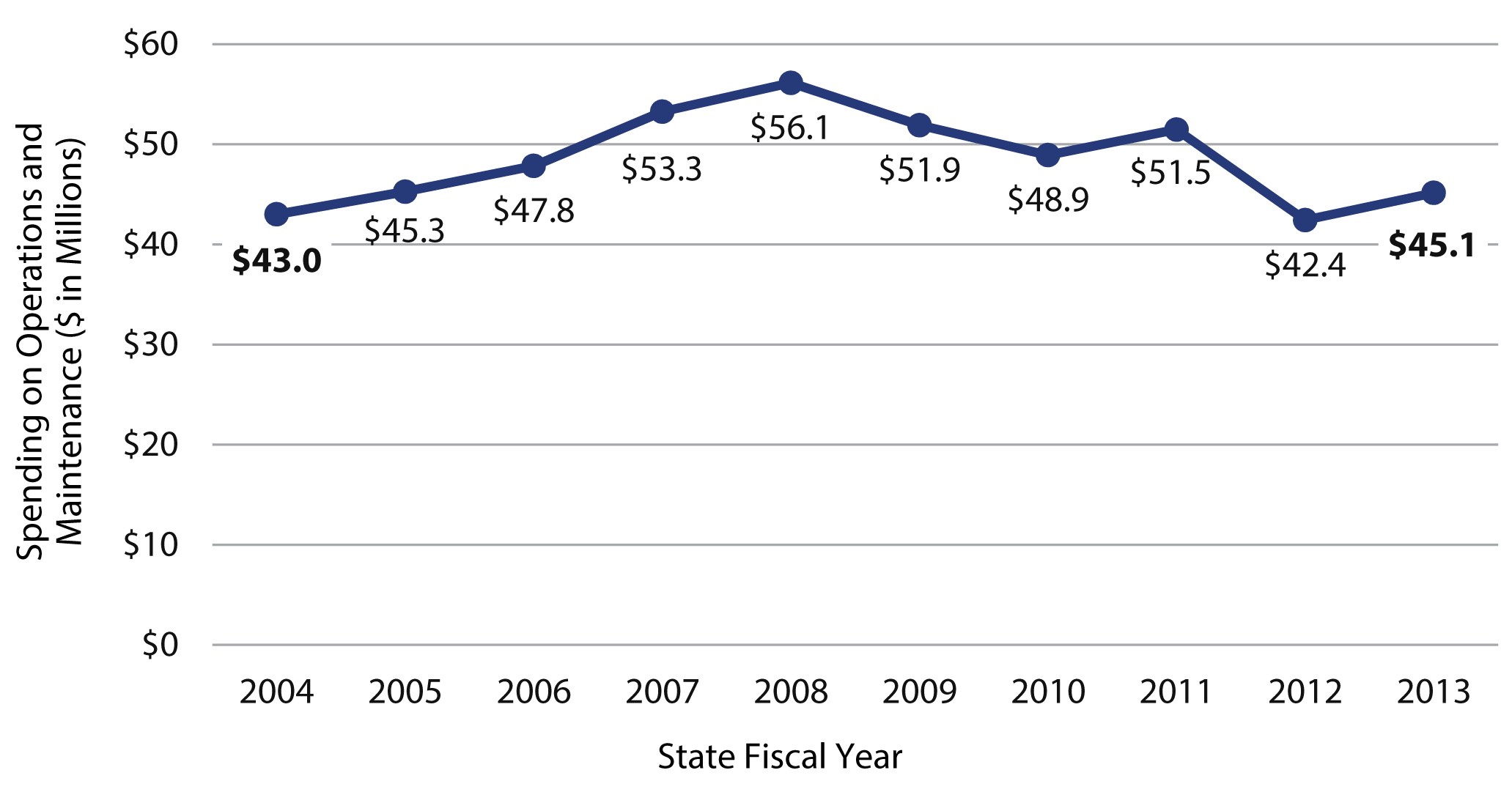

Each agency experienced a decline in General Fund State spending between fiscal years 2004 and 2013. Exhibits 11, 12, and 13 show each agency’s inflation-adjusted spending on operations and maintenance over 10 years.

State Parks had the most variation in spending, and the greatest shift away from the General Fund to other state funds.

- State Parks spent more to manage parks in FY 2013 than in FY 2004 (Exhibit 11).

- Funding has shifted away from General Fund State.

- General Fund State dropped from 61% of funding in FY 2004 to 19% in FY 2013.

- Other state funds, including the Discover Pass, increased from 38% to 81% of funding.

Exhibit 11 - Estimated State Parks spending for operations and maintenance, FY 2004 to FY 2013 (dollars in millions, adjusted for inflation)

Source: JLARC staff analysis of data from LEAP and State Parks, Fiscal Year 2004 through Fiscal Year 2013.

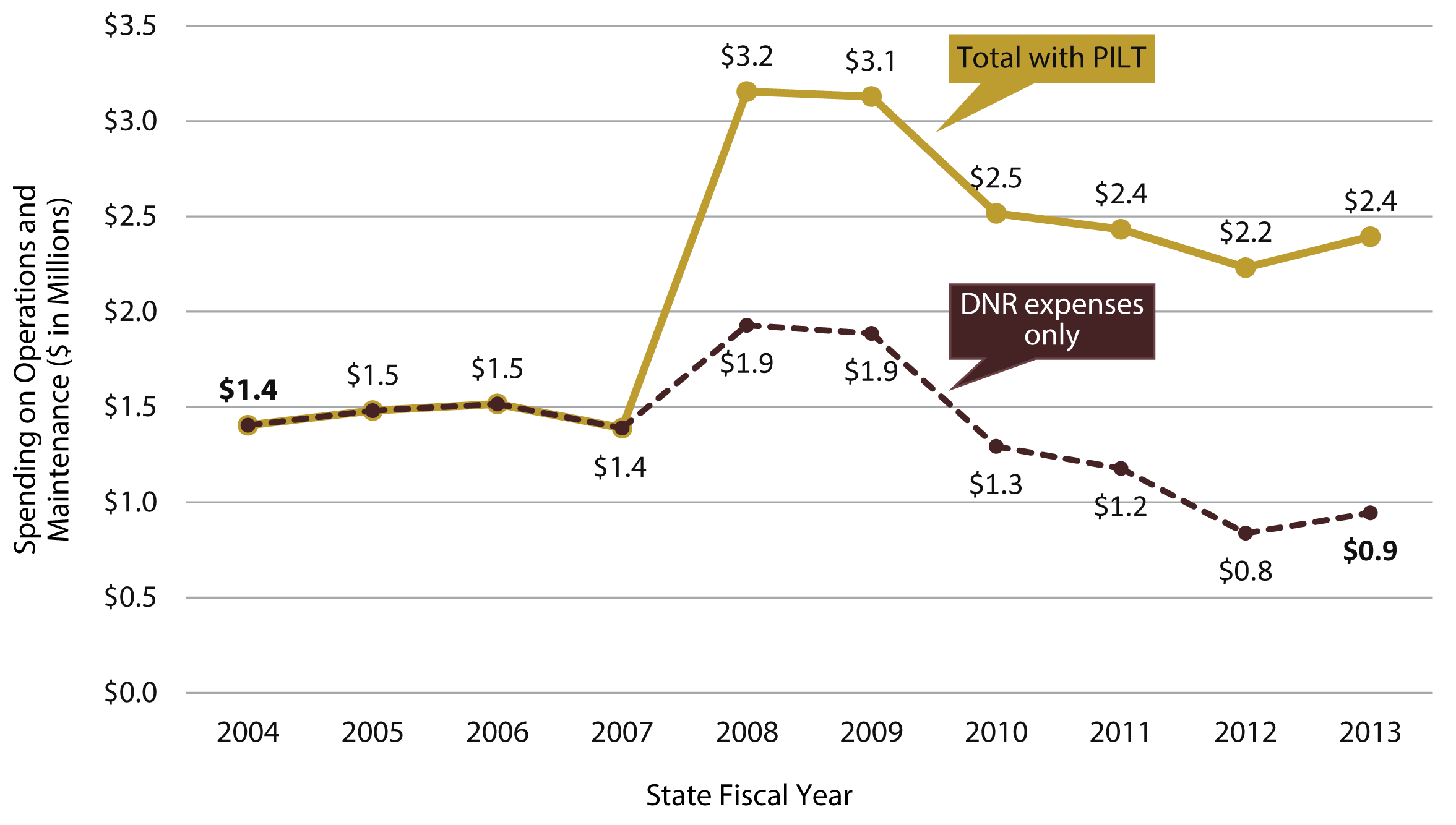

Spending on DNR’s natural areas increased overall due to the addition of payments in lieu of taxes (PILT) in 2008. Absent PILT, DNR spending for operations and maintenance decreased and shifted to other state, federal, and private/local funding sources.

- Absent PILT, DNR spent less to manage natural areas in FY 2013 than in FY 2004 (Exhibit 12).

- Funding shifted from General Fund State to other state, federal, and private/local resources.

- General Fund State dropped from 74% of funding in FY 2004 to 22% in FY 2013

- Other state funds increased from 1% to 63% of funding

- Federal, local, and private sources increased from 1% to 15% of funding

Exhibit 12 - Estimated spending for natural areas operations and maintenance, FY 2004 to FY 2013 (dollars in millions, adjusted for inflation)

Source: JLARC staff analysis of data from LEAP, State Treasurer, and DNR, Fiscal Year 2004 through Fiscal Year 2013.

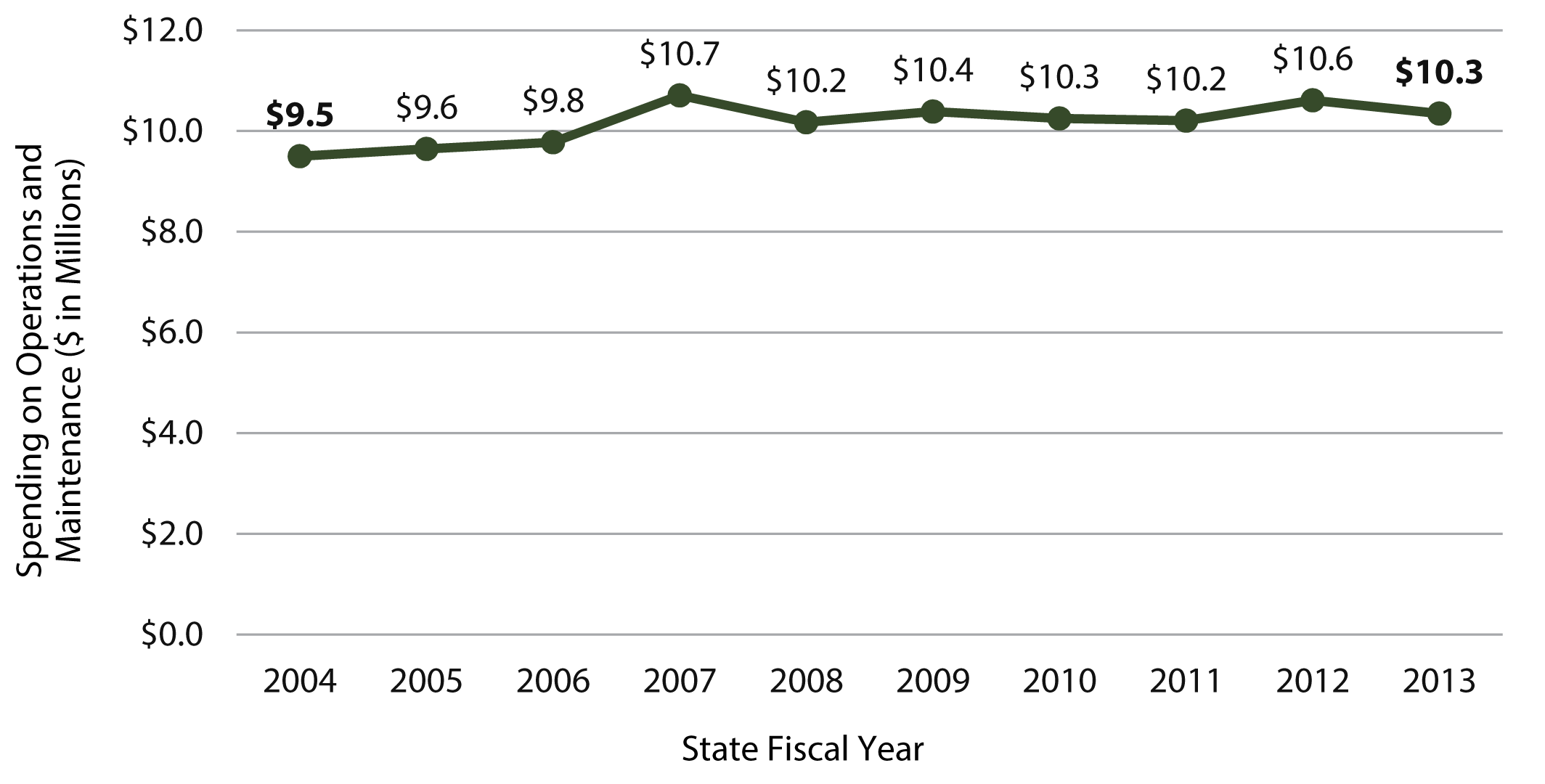

WDFW had a slight increase in spending and shifted to other state, federal, and private/local funding sources.

- WDFW spent more to manage wildlife areas and water access sites in FY 2013 than in FY 2004 (Exhibit 13).

- Funding shifted from General Fund State to federal, and private/local resources.

- General Fund State dropped from 20% of funding in FY 2004 to 8% in FY 2013

- Other state funds decreased from 34% to 33% of funding

- Federal, local, and private sources increased from 46% to 59% of funding

Exhibit 13 - Estimated WDFW spending for operations and maintenance, FY 2004 to FY 2013 (dollars in millions, adjusted for inflation)

Source: JLARC staff analysis of data from LEAP and WDFW, Fiscal Year 2004 through Fiscal Year 2013.

-

Analysis and reporting hindered by agency systems

Agencies store land management information in multiple databases and files. They can compile information maintained in different systems, but doing so is time consuming and potentially costly.

Inventory data in multiple systems

None of the three agencies has a comprehensive database that includes all of the relevant information to answer key questions about acquisitions and costs.

- Each agency has a unique database to record basic information about property acquisitions (e.g., acreage, county, ownership type, and acquisition date).

- Each agency used paper and electronic files, as well as employees’ personal knowledge to provide information such as the property’s general purpose (e.g., critical habitat), specific intended and current use (e.g., grasslands for sharp-tailed grouse), and the restoration and development work the agency intends to perform (e.g., replant native grasses).

- Each agency relied on additional databases to report the sources of acquisition funding.

- Each agency uses different names in its databases and files to refer to the same acquisition or management unit.

Operating costs tracked by larger units

Each agency accounts for expenditures and acres on different scales, making it difficult to compare the acreage, management plan, and expenditures for locations across the state.

- State Parks maintains acreage data for individual parks, historical sites, and other properties. The agency tracks expenditures by “park area.” Each park area includes a major park and, in some cases, one or more small parks and properties.

- WDFW tracks acreage by wildlife area, and groups some areas together to track expenses. The agency maintains data about each water access site but tracks expenses by six regions that include between 52 and 192 sites each.

- DNR tracks all of its natural area expenditures statewide and does not maintain data about expenses for each natural area.

-

Access and learn about the inventory

Inventory includes state parks, natural areas, wildlife areas, and water access sites

The inventory (click here) and analysis comprises properties acquired to be part of the state park system, DNR’s natural area preserves or natural resource conservation areas, or WDFW’s wildlife areas or water access sites.

- The state park system has 124 official parks that, along with numerous satellite properties, provide recreation, protect historical landmarks, and offer habitat benefits.

- DNR’s natural areas program includes 55 natural area preserves and 36 natural resources conservation areas. The areas are managed for habitat, but also may provide passive recreation such as bird watching and hiking.

- WDFW manages 33 wildlife areas to preserve habitat for fish and wildlife species and provide hiking, fishing, hunting, and wildlife viewing.

- WDFW manages 690 water access sites that provide boating access to lakes, rivers, and marine areas.

JLARC staff excluded properties that may provide recreation and habitat, but not as a primary goal (e.g., DNR trust lands).

Recreation and Conservation Office (RCO) inventory has different focus

The Recreation and Conservation Office (RCO) has developed a map-based inventory of recreation and habitat land in Washington owned by federal, state, and local governments. This inventory includes all lands owned by State Parks, DNR, and WDFW, including trust lands and land acquired before Fiscal Year 2004. JLARC staff obtained acquisition and disposal information directly from the agencies instead of the RCO inventory because our proviso required additional information. The RCO inventory will inform the JLARC report due in April 2015.

How agencies acquired land

State Parks, DNR, and WDFW acquired land by buying it, accepting donations, trading land with other government agencies, entering into management agreements or leases, or securing permits. The agencies did not use condemnation.

The acquisitions in the inventory take the following forms:

- The state owns the property and holds the underlying title.

OR

- The state does not own the property but has one of the following:

- A legal agreement (called a conservation easement) that restricts the landowner’s activities and protects the land’s conservation values. The private landowner, rather than the state agency, retains primary responsibility for managing the property. For example, WDFW purchased conservation easements in the Methow Valley to limit development and protect riparian habitat.

- A contract through which the state accepts long-term management responsibility. For example, State Parks has a management agreement with a private landowner to provide swimming and boating at Riverside State Park.

- Legal authorization to provide access to and public use of privately held land. For example, State Parks has secured permits that allow public access to trails from private property.

How agencies disposed of land

State Parks and WDFW disposed of land by selling it, transferring it to another government agency, or cancelling leases or management agreements. DNR did not dispose of recreation or habitat land during the period under review.

Formal analysis of economic costs and benefits not routinely performed or required

The Legislature directed JLARC staff to evaluate measures used to understand the economic effects of public recreation and habitat lands. State Parks, DNR, and WDFW do not routinely conduct formal economic analyses of their recreation and habitat lands, and there are no requirements for them to do so.

JLARC staff worked with economists from Washington State University to review how formal economic analyses can be used to understand recreation and habitat lands. There is no single best approach to performing an accurate economic analysis. There are some key questions policy makers should ask to understand the results of an economic analysis. A JLARC report in April 2015 will address additional considerations regarding economic analysis of recreation and habitat lands.

-

Formal economic analysis for acquisitions not required

State law does not require agencies to analyze the economic costs and benefits of properties before or after they acquire recreation or habitat land. In addition, state and federal grant programs do not require formal economic analysis of proposed acquisitions. The only exception is a statutory requirement to conduct periodic economic analysis of state trust lands.

There are certain circumstances under which state law requires State Parks, DNR, or WDFW to examine the economic effects of its actions other than acquisitions. These requirements are focused on specific rule-making activities and effects on small businesses. For example, DNR is required to perform benefit-cost analysis (BCA) for rules related to protecting habitat for threatened species and WDFW is required to perform BCA for construction projects in state waters.

-

State agencies do few formal economic analyses

State Parks, DNR, and WDFW do not regularly conduct formal benefit-cost analysis or other forms of economic analysis for acquisitions. The agencies have not adopted formal guidelines or principles for conducting economic analysis on new acquisitions or lands they already own.

Policy goals are primary focus at acquisition

Agency statutes and decision criteria for selecting new acquisitions emphasize policy goals rather than the economic effects of the lands. Decisions are prioritized based on preservation and conservation needs, maximizing recreational opportunities, and protecting cultural, historical, and ecological resources. If considered, the economic benefits of the lands are secondary and described in general terms (e.g., “will increase tourism”).

Limited studies of existing lands

State Parks and WDFW have hired consultants to conduct a limited number of economic studies. The scope and content of these studies vary. For example, in 2002, State Parks contracted for a study of the economic impacts of visitors to all of Washington’s state parks. In 2014, WDFW contracted for an economic analysis of conservation efforts at two wildlife areas in Okanogan County (Methow and Okanogan-Similkameen).

-

Caution needed when citing other studies

Agencies frequently use the results of studies conducted by federal agencies or private organizations when describing the economic benefits of their lands.

While many of these studies are well-designed and reliable, agencies and the general public need to be cautious when extending general conclusions to specific lands. Additional analysis is often needed to determine how the results might apply to particular lands or properties. For example, WDFW has cited fishing and hunting expenditures from a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) recreation survey as evidence of the contribution of WDFW lands. Likewise, State Parks has cited the results from national studies by the Outdoor Industry Association (OIA) to highlight the value of parks on the state’s economy. There are several concerns with applying the results of these studies to agency-owned lands:

- National and privately funded studies, including the USFWS and OIA studies, often analyze the effects of activities on all public and private recreation and habitat lands throughout the state or the country. Applying the same results to agency-owned lands may misstate the effects of these state lands.

- Even if the data is specific to state-owned lands, the results are not necessarily true for each specific property or site owned by an agency.

-

Other states have similar practices

Washington practices regarding economic analysis are similar to those in other Western states:

- Other states often cite the results of national and privately funded studies. They make statements about the economic values of their public lands based on these broader study results.

- States hire experts to perform economic studies rather than conducting them in-house. These studies are done on an occasional basis rather than on a routine schedule.

- Some states describe economic effects in their land acquisition process. They typically provide qualitative information rather than a formal economic analysis.

-

Federal analyses are not focused on acquisitions

Federal land management agencies, such as the U.S. Forest Service and National Park Service, do not use economic analysis for decisions about land acquisitions or disposals. Instead, formal economic analysis is used to understand the costs, benefits, and economic contributions of larger land bases, such as national forests located in a specific region of the country.

Some federal laws, regulations, and executive orders require formal economic analysis for activities including environmental regulations, landscape-level planning, and designations of critical habitat under the Endangered Species Act.

The National Park Service models the effects of park visitor spending for the entire national park system and at least 20 individual national parks. While data collection for the model can be expensive, at least one state (Pennsylvania) has adopted this model to assess the effects of park visitor spending on local jobs, business income, and employee wages.

-

There is no single best approach

When studying the economic effects of public lands, no one approach is considered to be the best or most appropriate form of analysis to use. Separate analyses of the same lands may offer different but equally valid results depending on the questions addressed and the assumptions made.

The results of these studies depend on many factors, including the particular location under review, the type of land use, the relative abundance or scarcity of land for different uses, and the business, social, and cultural climate of the area.

Analyses answer different questions

There are many valid approaches to formal economic analysis. Those commonly used to assess public lands can be grouped into two categories: benefit-cost analysis and economic activity analysis. These studies answer different questions about the economic influence of public lands.

Benefit-cost analysis answers whether overall benefits exceed the overall costs

Benefit-cost analysis (BCA) seeks to determine whether the overall benefits from a particular action or program will exceed the overall costs over the lifetime of the project or program. The results are often expressed as a ratio of the benefits compared to the costs. BCA recognizes benefits and costs that typically do not have a monetary value, such as water quality, health impacts, and cultural significance.

Economic activity analysis answers whether economic measures increase or decrease

Economic activity analysis, often in the form of an input-output model, is used to understand the effect of projects or programs on different measures of the economy. The results of an economic activity analysis reflect the dollars spent in a region and can be expressed as the number of jobs created, business income and wages generated, or an industry’s output over a particular time period, usually one year. There are two common forms of activity analysis:

- A contribution study highlights the gross positive effects of an action or program. It does not account for any negative effects it may have on different sectors of the economy.

- An impact study highlights the net changes to the economy associated with an action or program, including any shifts in spending, jobs, or wages from one sector to another.

Scale and resource requirements vary

Benefit-cost and economic activity analyses are typically performed at a broad scale. Most individual state acquisitions would result in small changes that are often difficult to identify in a large economy.

In general, benefit-cost analyses are best suited for large scale changes in land use, when much is at stake in terms of dollars and competing public interests, or when the effects of a particular action are anticipated to be spread over many years. Benefit-cost analyses tend to be resource-intensive in terms of time, costs, and level of expertise required. Data collection efforts are often difficult and expensive.

In comparison, activity analyses can be used for somewhat smaller-scale projects, such as understanding the impacts of certain lands in a particular county or region of the state. While specific expertise is required to conduct them, they are well suited for projects in which changes in the economic use of the land is likely.

-

Key questions to ask when reviewing results

Legislators and the public are frequently presented with findings from economic analysis. While it is difficult to judge the validity and reliability of an analysis without full knowledge of the methods used, there are some key questions to keep in mind that will help place the results in appropriate context.

For all studies:

Question Notes Are the results focused on the local, state, or national economy? Studies are typically conducted from one economic perspective. For example, a project may change a county or city’s economy, but if the study is looking at statewide or nationwide effects, the changes may seem very minimal or nonexistent. Knowing which economy the results explain will help in interpreting the meaning of the results. Are the results specific to particular lands? Study results may reflect a broader land base than a specific project or area of interest. This may overstate or understate the influence of a specific property or site. It is important to determine how similar or different the lands of interest are to the lands that were analyzed. What data, time, or resource constraints affected the study? Conducting economic analysis requires sufficient time and data as well as technical expertise. Researchers need to make assumptions when data is unavailable. Best practices for individual approaches exist, but they are highly technical and methodology specific. For benefit-cost analyses:

Question Notes What benefits and costs were included? A benefit-cost analysis (BCA) should be comprehensive and reflect the interests of all stakeholders. A BCA can include factors that are difficult to quantify, such as environmental health or quality of life. If some costs or benefits are excluded, they should be clearly identified. For economic activity analyses:

Question Notes Are the results (e.g., jobs) a gross or net amount? A study that reports only the gross impact on the economy ignores how the spending affects other industries and may overstate impacts. For example, a study may consider only the positive contribution of additional park land, or it may also account for the loss of residential housing opportunities on that land. Both approaches give equally valid, but potentially very different, results. Did the study include both resident and non-resident spending? A study that reports both resident and non-resident spending may overstate the impact of public lands. This happens because some spending by residents on outdoor recreation may shift spending away from other local industries rather than add new money to the local economy. Do the results include just direct effects or all effects? Jobs and spending numbers may cover only “direct” impacts that come from visitors to recreation and habitat lands. Direct impacts include travel costs and fees paid to use the lands as well as supplies purchased for activities on those lands. This may understate the value generated by these visitors because it does not include the impact on industries that provide indirect services, such as manufacturers of camping and hunting equipment, or companies that provide food and other supplies to area restaurants.

A consolidated agency response was received from the Office of Financial Management, the Department of Fish and Wildlife, the Department of Natural Resources, the Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission, and the Recreation and Conservation Office. The agencies indicated they partially concurred with the Legislative Auditor's recommendation.

Authors of this Study

Rebecca Connolly, Project Lead, 360-786-5175

Stephanie Hoffman, Research Analyst, 360-786-5297

Ryan McCord, Research Analyst, 360-786-5186

John Woolley, Audit Coordinator

Keenan Konopaski, Legislative Auditor

Joint Legislative Audit and Review Committee

Eastside Plaza Building #4, 2nd Floor

1300 Quince Street SE

PO Box 40910

Olympia, WA 98504-0910

Phone: 360-786-5171

FAX: 360-786-5180

Email: JLARC@leg.wa.gov

Audit Authority

The Joint Legislative Audit and Review Committee (JLARC) works to make state government operations more efficient and effective. The Committee is comprised of an equal number of House members and Senators, Democrats and Republicans.

JLARC’s non-partisan staff auditors, under the direction of the Legislative Auditor, conduct performance audits, program evaluations, sunset reviews, and other analyses assigned by the Legislature and the Committee.

The statutory authority for JLARC, established in Chapter 44.28 RCW, requires the Legislative Auditor to ensure that JLARC studies are conducted in accordance with Generally Accepted Government Auditing Standards, as applicable to the scope of the audit. This study was conducted in accordance with those applicable standards. Those standards require auditors to plan and perform audits to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for findings and conclusions based on the audit objectives. The evidence obtained for this JLARC report provides a reasonable basis for the enclosed findings and conclusions, and any exceptions to the application of audit standards have been explicitly disclosed in the body of this report.

Committee Action to Distribute Report

On July 29, 2015 this report was approved for distribution by the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Committee.

Action to distribute this report does not imply the Committee agrees or disagrees with Legislative Auditor recommendations.

JLARC Members on Publication Date

Senators

Randi Becker

John Braun, Vice Chair

Sharon Brown

Annette Cleveland

David Frockt

Jeanne Kohl-Welles, Secretary

Mark Mullet

Ann Rivers

Representatives

Jake Fey

Larry Haler

Christine Kilduff

Drew MacEwen

Ed Orcutt

Gerry Pollet

Derek Stanford, Chair

Drew Stokesbary

Scope & Objectives

Why a JLARC Study of Public Recreation and Habitat Lands?

In the 2013-15 Capital Budget (ESSB 5035), the Legislature directed the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Committee (JLARC) to conduct a study of public recreation and habitat lands that would describe the characteristics and costs of recent acquisitions, evaluate cost and benefit measures for these lands, and address potential effects of these lands on county economic vitality.

State Agencies Acquire These Lands with Different Funds and for Different Purposes

Much of the Legislature’s assignment focuses on lands acquired by three state agencies: the Department of Natural Resources (DNR), the State Parks and Recreation Commission (Parks), and the Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW). State law authorizes these agencies to acquire land for recreation or habitat. The departments fund many of these acquisitions with state grants, federal grants, or direct capital budget appropriations. Agencies also acquire property through donations, exchanges, and land transfers. The fund source may restrict how recipients can use the money or land.

The Department of Natural Resources manages lands that produce income for schools, local services, and other purposes. Many of these sites offer recreational opportunities such as campgrounds and trails. Statute also authorizes DNR to establish natural area preserves and natural resource conservation areas to protect habitat, native ecosystems, and rare species.

The Department of Fish and Wildlife has statutory duties to protect fish, wildlife, and habitat and to provide hunting, fishing, and recreational opportunities. WDFW manages land for plant and animal habitat; some areas are also open to hunting, hiking, and other recreation. WDFW’s water access sites provide opportunities for activities such as fishing and boating.

The State Parks and Recreation Commission has a statutory duty to manage lands set aside for parks. This includes developed parks, heritage sites, interpretive centers, and historic structures. Many properties also provide habitat for plants and animals.

Public Habitat and Recreation Lands May Affect County Economic Vitality

State, federal, local, and tribal governments own land in Washington counties. Use of these lands for habitat or recreation may affect a county’s economic vitality. The Recreation and Conservation Office completed two studies of these lands in 2005, offering a framework to identify economic impacts. Since then, the Legislature has requested additional reviews of public recreation and habitat lands and their effect on county property taxes. This study will look broadly at impacts to county economic vitality and will consider changes in addition to property taxes.

Study Scope

JLARC staff will create an inventory of the recreation and habitat acquisitions made by DNR, WDFW, and Parks over the last ten years, including land characteristics and associated costs. The study also will identify recent trust land acquisitions on which DNR provides or plans to provide recreation. JLARC staff will work with natural resource economists to evaluate the measures used to estimate benefits and costs, and to identify mechanisms to estimate the impact of public recreation and habitat lands on the economic vitality of Washington’s counties.

Study Objectives

This study will address the following questions by January 2015:

- What recreation and habitat lands have the Department of Natural Resources, the Department of Fish and Wildlife, and the State Parks and Recreation Commission acquired over the past ten years?

- What is the current use of these lands? How does the current use compare to the intended use? What are the estimated costs to bring these lands to the intended uses?

- How much do the agencies spend to manage recreation and habitat lands?

- Are there best practices for estimating economic benefits and costs of recreation and habitat lands?

- What measures and techniques do state and federal agencies use to estimate the economic benefits and costs of recreation and habitat lands? How do those measures compare with best practices?

- What are the estimated acres of recreation, habitat, and other land owned by federal, state, tribal, and local governments in each of Washington’s counties?

In addition, the study will address this question by April 2015:

- How can the Legislature reliably estimate the impact to a county’s economic vitality from an incremental change in recreation or habitat land, when considered with other county characteristics?

Timeframe for the Study

Staff will present preliminary reports in January 2015 and April 2015, as described above. Staff will present a final report in July 2015.